- Home

- Middle East

- Trump’s New Doctrine: Transforming the War on Drugs into a Front Against Iran

©This is Beirut

Iran’s leveraging of its proxy Hezbollah has been central to the arguments for expanding U.S. counter-terrorism designations to include Venezuela and the cartels

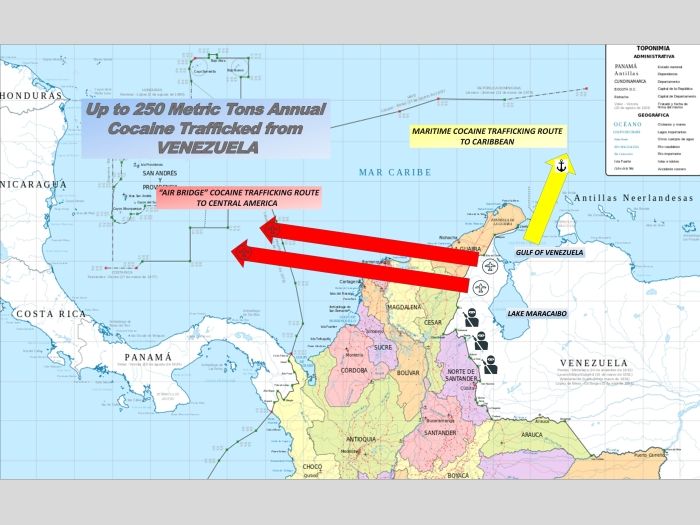

The string of U.S. strikes against alleged narco-trafficking boats in the Caribbean is not just a fresh phase in the war on drugs; it is a new operational theater in the proxy war against Iran.

The attacks—nearly a dozen over the last month—are the sharp tip of the Trump administration’s doctrine that treats Latin America’s cartels as not simply transnational criminal organizations but strategic weapons deployed by America’s adversaries in a global contest for power.

The Trump administration has not officially or directly linked the strikes to Iran, and little evidence has been shared to substantiate claims the vessels are trafficking narcotics for cartels.

But officials have repeatedly framed the campaign in terms of a broader war against state-sponsored narco-terror, including justifying the use of kinetic force under the designation of cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations because of “a convergence between (the cartels) and a range of extra-hemispheric actors, from designated foreign-terror organizations to antagonistic foreign governments.”

Under this doctrine, Latin America’s cartels are being leveraged as a potent weapon in a broad asymmetrical campaign by the West’s key adversaries, especially China, Russia and Iran, to undermine U.S. global hegemony.

“Transnational criminal organization-driven corruption and instability open space for China, Russia and other malign actors to achieve strategic ends and further their agendas,” Admiral Alvin Holsey, commander of the U.S. Southern Command responsible for the boat strikes, told lawmakers in February. Southcom says those TCOs are responsible for killing hundreds of thousands of Americans through overdoses and annually earn five times the combined military budgets of every nation in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Holsey also called out Iran in particular, saying Tehran has for decades built political, military and economic clout in Latin America through sympathetic authoritarian regimes—especially Venezuela and Bolivia—and has increasingly developed criminal networks in the region. In particular, Iranian partner Lebanese Hezbollah’s narco-trafficking and money-laundering operations “threaten regional stability and raise millions of dollars for the terrorist organization to plan attacks worldwide,” the Southcom commander said.

A chief champion of this doctrine within the Trump administration is Joseph Humire, deputy assistant secretary of war for Western Hemisphere affairs and author of the 2016 book Iran's Strategic Penetration of Latin America.

“Venezuela is a proxy of China, Russia, and Iran; they all understand that mass migration can be employed as a weapon of asymmetric warfare to erode national borders, steal sovereignty, and eventually have the United States collapse from within,” said Humire in March, just prior to his June War Department appointment, at a House Oversight law enforcement subcommittee hearing on illegal aliens.

“Nation-states are now using these transnational criminal organizations,” he said, citing in particular Hezbollah and Tren de Aragua, the Venezuela-based transnational criminal organization targeted by the Trump administration. “You are seeing an element of ability to put these criminal organizations into overdrive” under the convergence concept, “when you get terrorist organizations, criminal organizations, and an array of illicit actors converging together under logistics.”

Humire cited the expansion of Tren de Aragua from four states to more than 23 states in the U.S. over the last year. “That happens because there is a government back in Venezuela that is providing guidance, direction, and resources to be able to expand throughout the country,” he added.

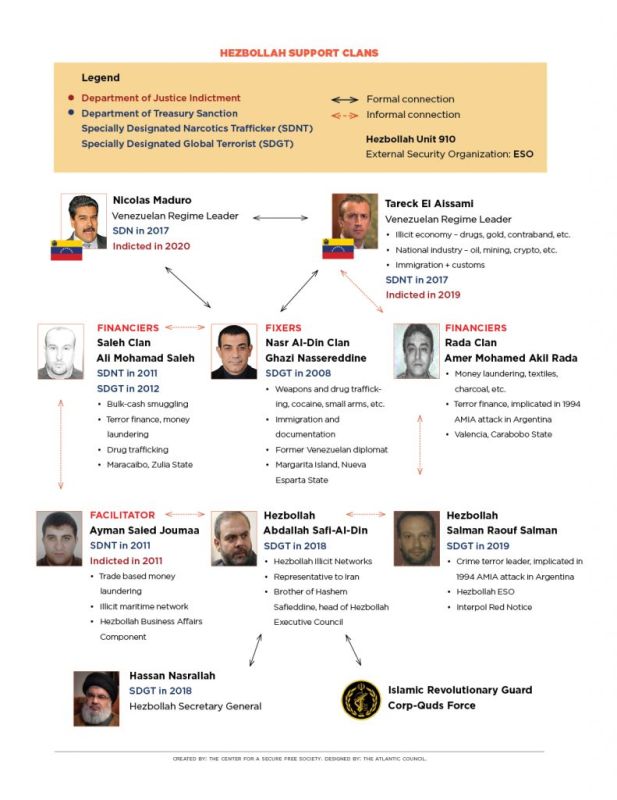

Humire is also the author of a 2020 paper published by the Atlantic Council, The Maduro-Hezbollah Nexus: How Iran-backed Networks Prop Up the Venezuelan Regime, that details two decades of strategic collaboration between Tehran, the Chavista regime and their criminal proxies. “The Maduro regime and Hezbollah have exploited legal and policy vacuums to turn Venezuela into a central hub for the convergence of transnational organized crime and international terrorism,” Humire wrote.

“The dual-use nature of Iran’s cooperation with the Maduro regime, layered with the illicit finance connections of its facilitators and Hezbollah’s established crime-terror network in Venezuela, creates a tier-one national security concern for the United States—one that is multifaceted and requires a robust response,” the future deputy secretary wrote in the 2020 paper.

“No other organization on our (Foreign Terrorist Organization) list embodies the crime-terror convergence more than Lebanese Hezbollah,” Humire told lawmakers at another hearing in 2018.

The recently renamed Department of War did not respond to a request for comment.

Source: The Atlantic Council

The convergence doctrine—which has been recognized by the Treasury Department, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Drug Enforcement Agency for years but often dismissed or ignored by some in the national security community—is now being taught by the Department of War.

“A growing climate of insecurity and economic opportunities are being leveraged by China, Russia, and Iran through predatory activities and criminalities to finance greater insecurity and chaos in the region,” said David Luna, a veteran U.S. national security official who now leads the International Coalition Against Illicit Economies, at an intelligence symposium hosted by the Department of War’s Irregular Warfare Center in June.

The growth of Latin American criminal networks, their ability to raise hundreds of billions of dollars in income and arm themselves in competition with state militaries, and their cooperation with foreign adversaries mean “a perfect storm is brewing,” he said, warning the national security officials in the audience that they “must move with greater urgency to confront criminal threat convergence.”

Iran’s leveraging of its proxy Hezbollah has also been central to the arguments made in favor of expanding terror designations to include Venezuela and the cartels with which it has contracted professional money-laundering and narco-trafficking operations. Trump’s first administration began laying the groundwork for the designation when the Department of Justice set up a special Hezbollah Financing and Narcoterrorism Task Force, naming the Lebanese organization’s criminal operations as one of the top five TCOs. Over the next two years, federal prosecutors unveiled an array of indictments against top current and former Venezuelan officials, accusing Nicolas Maduro and his regime of participating in a violent narco-terrorism criminal conspiracy between the Cartel de Los Soles—so named because of the involvement of top Venezuelan military officials—and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC).

Although those indictments cited the Iranian connection, it was the prosecution of former Venezuelan parliamentarian Adel El Zabayar as a member of Cartel de Los Soles that cited the Hezbollah connection in particular. Among their allegations, prosecutors said El Zabayar obtained anti-tank rocket launchers from the Middle East for the FARC as partial payment for cocaine and recruited terrorists from Hezbollah and Hamas “for the purpose of helping to plan and organize attacks against the United States.”

Source: U.S. Department of Justice

Source: U.S. Department of Justice

The convergence concern, according to current and former officials, is not just about Iran financing itself and its proxies, which allows those terror groups to rearm and reconstitute in the wake of the war.

The fear is also that these networks have become operational platforms that threaten the U.S. and its interests in the Western Hemisphere, fundamentally changing the geopolitical calculus, including the extent to which Washington is willing to challenge Tehran in direct warfare. Because of their size, scope and operational capabilities, those networks can efficiently and covertly move men, money, arms and intelligence into strike positions, current and former Western intelligence and security officials say. And they help create the trade and finance networks that allow Iran and other authoritarian regimes opposed to U.S.-led liberal democratic principles to sidestep one of the West’s most potent tools of diplomatic coercion: sanctions and export controls.

Former Southcom Commander Admiral Craig Faller warned lawmakers in 2020 that, in addition to its illicit trafficking and money-laundering operations, Hezbollah gave Tehran a strategic position in the Western Hemisphere, including through psychological warfare and its maintenance of weapons caches throughout the Americas.

“Having a footprint in the region also allows Iran to collect intelligence and conduct contingency planning for possible retaliatory attacks against U.S. and/or Western interests,” Faller said.

A case in point, the U.S. secretly bolstered security at federal buildings against possible Iranian attacks after assassinating former Islamic Revolutionary Guard Commander Qassem Soleimani, concerned about Hezbollah as the threat vector.

Another example is the 2017 arrest of two men, Ali Mohammad Kourani and Samer El Debek, for working as agents of Hezbollah’s core terror operations group, the Islamic Jihad Organization. Kourani, who was given a 40-year sentence in 2019 for his crimes, was caught surveilling federal buildings, international airports and other critical infrastructure, including the Panama Canal and federal offices in New York City.

“Hezbollah’s presence and financial clout through these illicit activities is a threat, not just because of their cooperation with crime, but also potentially because they can be an accessory to terrorist attacks,” said Emanuelle Ottolenghi, a veteran security analyst specializing in Hezbollah’s operations in Latin America.

More recently, Southcom said Iran has leveraged Hezbollah’s foothold in the region to increase its ideological influence in Latin America, conducted large-scale psychological warfare to promote its interests in attacking the West and Latin America, and delivered coastal defense missile patrol boats to Venezuela. Furthermore, Iran and its agents have transitioned from simply categorizing and tracking targets for possible attacks to launching plans, including the attempted assassination of Israeli businessmen in Colombia, Southcom said.

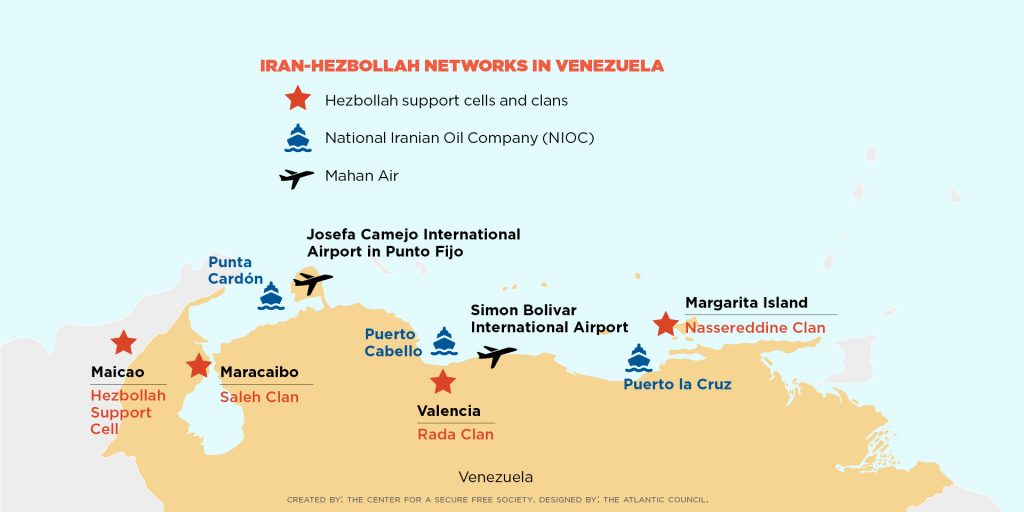

Numerous Hezbollah-tied money-laundering and narco-trafficking operations throughout the Americas reveal multi-billion-dollar operations and the extent to which Tehran’s decades-long strategy is paying political dividends. Hezbollah operatives have been successfully placed into senior government positions, especially in Venezuela, where they have orchestrated and managed state-sanctioned money-laundering and narco-trafficking operations with the aid of the country’s top officials.

Source: Blox Images

Former Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez’s head of military intelligence, Hugo Carvajal, was “the main man between Venezuela and Iran, the Quds Force, Hezbollah and the cocaine trafficking.” Carvajal in June pleaded guilty to narco-terrorism, weapons and related charges for his role within the Cartel de Los Soles.

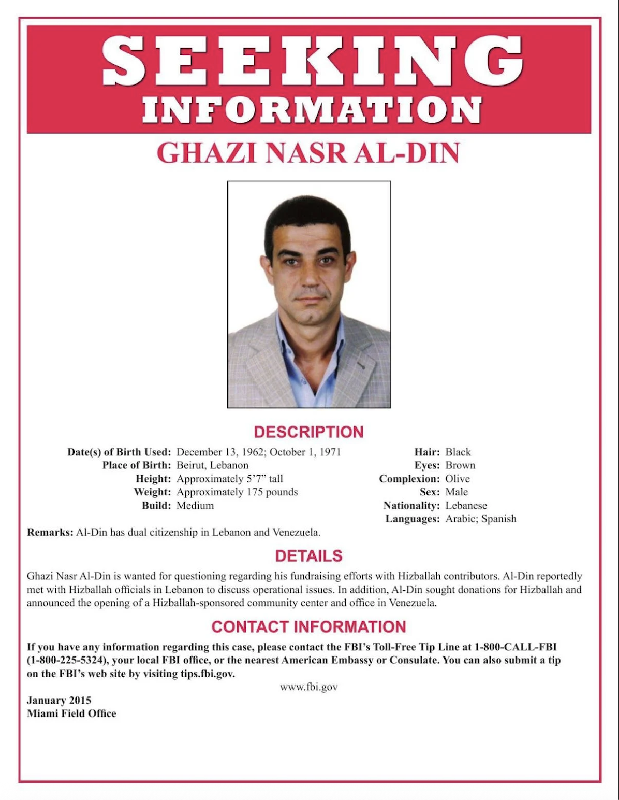

The U.S. Treasury nearly two decades ago identified Beirut-born Ghazi Nassereddine, who emigrated to Venezuela shortly after Hugo Chavez came to power, as a Hezbollah financier and power broker for the terror group while he served as the number two official in the country’s embassy in Damascus, Syria. Officials, including the FBI, later identified Nassereddine as a key Hezbollah asset because of his close personal relationship to Chávez’s justice and interior minister at the time, Tareck El Aissami, and his infiltration of the country’s diplomatic apparatus. That position, say current and former U.S. officials, helped Hezbollah and Iran to significantly expand their operations in their region, including through the transfer of agents who were given new Venezuelan identities.

U.S. authorities later accused El Aissami, Venezuela’s former vice president and oil minister, of using his government positions to oversee drug trafficking and money-laundering operations, including working with the Los Zetas cartel and a Venezuelan drug kingpin, Walid Makled, who was tied to Nassereddine.

Aligning with Nassereddine’s operations, Venezuelan intelligence alleges El Aissami was also actively working for Hezbollah. One of Nassereddine’s brothers, a former Venezuelan congressman, helped manage money-laundering operations from Margarita Island, where another brother also oversaw paramilitary training centers on the island, recruited radicalized Venezuelans and sent them to Iran for advanced training, according to a former senior State Department official.

“Virtually every indicted Hezbollah operative and facilitator involved in terror plots, terror finance schemes, weapons and technology procurement, trade-based money laundering, and drug trafficking on behalf of Hezbollah was a dual national of Lebanon and another country,” Ottolenghi warned the House Homeland Security Subcommittee on Counterterrorism and Intelligence in 2018.

The son of a Lebanese immigrant to Colombia, Alex Saab served as the principal financial fixer for Venezuela’s Maduro regime, orchestrating international networks that linked Venezuelan state enterprises with Iranian and Hezbollah-connected actors to evade U.S. sanctions and launder illicit proceeds.

U.S. prosecutors and officials said Nader Mohamed Farhat ran money-laundering operations for narco-traffickers as a member of Hezbollah, securing an estimated $300 million a year for the group. Farhat is the brother-in-law of Walid Sweid, a businessman who has been accused of laundering hundreds of millions of dollars, including for Hezbollah, and has ties to Paraguay’s leadership.

Humire, in his March testimony before the House Oversight subcommittee, also cited the 2011 case of Ayman Joumaa, the Lebanese-Colombian financier and facilitator for both the Los Zetas Mexican cartel and Hezbollah, who was estimated to have laundered roughly $200 million a month before his indictment.

But the war with Israel has heavily dented Hezbollah’s Lebanese operations, squeezing the financing critical to rearming, recruiting and maintaining a fighting force. Along with funding from Iran now constituting a smaller share of its financing, this suggests Hezbollah will now rely more heavily on its criminal networks across the globe, including throughout Latin America, to generate revenue.

“With its leadership decimated and operational capabilities significantly degraded, Hezbollah’s future as a state-sponsored terrorist organization is in question,” analysts for the War Department’s Irregular Warfare Center said in a recent post. “As a result, Hezbollah may consider pivoting more towards insurgent tactics and increasing their reliance on illicit networks for funding and survival,” the War Department-funded analysts said, pointing to Latin America in particular.

That is one of the reasons why the U.S. is ratcheting up its pressure on Hezbollah’s financial operations, issuing new sanctions and bounties for its operatives, including in the tri-border region, and adding Cartel de los Soles to its terror lists.

Those designations and the accompanying information provide data points to link one of the few cartels named in the strikes, the Tren de Aragua, to Hezbollah, albeit indirectly.

“The Cartel de los Soles supports Tren de Aragua in carrying out its objective of using the flood of illegal narcotics as a weapon against the United States,” said the U.S. Treasury, whose actions are bolstered with declassified intelligence to clear legal hurdles, in its July designation.

The TdA was born out of prisons in the Venezuelan state El Aissami previously governed, thus his moniker, ‘narco de Aragua,’ while the Cartel de Los Soles was named in the 2020 El Zabayar indictment as working directly with Iran, Syria’s former genocidal dictator, Bashar al Assad, and Tehran's proxies.

As a member of the Cartel de Los Soles, El Zabayar and other Venezuelan officials recruited Hezbollah and Hamas operatives, coordinated with Iran and Syria, and sought weapons and training from the Middle East to build a terrorist cell in Venezuela capable of attacking U.S. interests, prosecutors said.

Beyond the sanctions and kinetic strikes and a new task force, the Trump administration has yet to fully flex its financial and legal authorities in its broader convergence war, say former government officials.

By designating the cartels as foreign terrorist organizations, the administration has unlocked a suite of terrorism-specific authorities that were never available under traditional drug laws. The move allows the government to impose asset freezes, immigration bans, and criminal penalties for anyone providing “material support” to these groups, a framework originally built to fight al-Qaeda and ISIS. That opens up prosecutions against anyone seen as a facilitator, including bankers, insurers or shippers, involved in moving cartel funds or goods, under terrorism charges rather than routine money-laundering counts.

At the U.S. Treasury, officials are invoking Executive Order 13224, the government’s principal counter-terrorism sanctions tool, to freeze cartel assets worldwide and penalize any bank or shipper that does business with them. That order’s secondary-sanctions reach goes well beyond the older Kingpin Act, effectively globalizing the enforcement regime and turning the fight against Latin America’s cartels into a test case for applying counter-terrorism law to organized crime, say those former U.S. security officials.

Lawmakers and former U.S. security officials say the administration calls into question its own commitment to the policy in a host of actions they say fundamentally undermine authorities’ ability to detect and disrupt convergence networks, including some of Trump’s pardons and the rollback of one of the most powerful tools given to law enforcement to uncover illicit activity.

Still, the strikes against the narcotrafficking boats may just be the first broadside, with Trump and other senior officials signaling a deepening of the proxy war into Venezuela itself.

Under the invoked counter-terror authorities, the U.S. has readied a legal case to conduct lethal or covert operations against designated cartels without host-nation consent—the same legal rationale behind recent boat and drone strikes framed as counter-terror missions.

Maduro has in recent days mobilized his Bolivarian forces in preparation for land-based operations as the U.S. positioned its naval forces off Venezuela’s coast, including an aircraft carrier and other Navy warships capable of deploying missiles.

Trump earlier this week dismissed the idea that the U.S. was preparing for war against Venezuela but said Maduro’s days were numbered.

But the administration’s message is clear—it is not just Venezuela that is in Washington’s sights.

“We’ve got assets in the air, assets in the water, and assets on ships, because this is a deadly serious mission for us, and it won’t—it won’t stop with just this strike,” Pete Hegseth, the secretary of war, said in September after another of the boat strikes. “Anyone else trafficking in those waters who we know is a designated narco-terrorist will face the same fate.”

Read more

Comments