Lebanon has an exceptionally dense civil society sector. Hundreds of local NGOs receive funding from international organizations such as the European Union, various United Nations agencies, private foundations like Ford, Rockefeller and Open Society, as well as contributions from the diaspora. Most of this funding is fully declared, independently audited and included in donors’ annual reports.

On the surface, nothing seems out of the ordinary. Yet some organizations have found ways to obscure certain funding sources to better serve their agendas. A prominent example is Kulluna Irada, a “citizen-led political advocacy organization,” which publicly claims to receive contributions solely from Lebanese members and denies any support from Open Society. For context, George Soros’s Open Society Foundations (OSF), active in Lebanon since 2001, officially fund projects promoting human rights, social justice and press freedom. Their global reports note regional allocations without systematically naming each recipient, leaving some room for ambiguity.

From November 2019 onward, Soros’s name became closely linked to Kulluna Irada, as multiple investigations revealed an indirect external funding mechanism through OSF that benefited the organization. The question remains: to what purpose?

On March 7, 2020, exactly one year after Lebanon’s economic crisis erupted, former Prime Minister Hassan Diab announced the country’s first-ever sovereign default, unable to service a debt of $92 billion. While the collapse might have been avoidable, many insiders reportedly contributed to, or even encouraged, its inevitability.

At the time, former Finance Minister Ghazi Wazni “ignored the solutions we proposed to prevent default and enable a debt restructuring without imposing heavy costs on the Treasury,” said an expert close to the matter, speaking anonymously. “Diab and his government also disregarded these recommendations, effectively carrying out what appears to have been a politically motivated plan.” Sources with high-level knowledge told This is Beirut that Diab and his crisis management team “were fully aware of the impending default and, for purely political reasons, allowed it to happen.”

During Diab’s tenure (January to August 2020), a Lebanese negotiating team was formed under Wazni. Its key members included Alain Bifani, former Director General of the Ministry of Finance and permanent member of the BDL Central Council; Henri Chaoul, financial advisor and board member of Kulluna Irada, an organization with alleged ties to George Soros; and Talal Salmane, former economic advisor to the Ministry of Finance. Two additional advisors, Georges Chalhoub and Leila Dagher, directly represented the Prime Minister.

According to their claims, the default was “inevitable, even necessary.” Experts and decision-makers argued that funds intended for foreign creditors should instead meet the basic needs of a population cut off from its own banks. But this was a misleading pretext.

Over two years, billions spent on subsidies for wheat, fuel and essentials were largely wasted, while the crisis worsened. These subsidies cost the state between $15 and 17 billion since early 2020 – more than three times the $9 billion (with interest) needed to cover the 2020-2021 eurobond debt, plus an additional $2 billion for 2022, excluding interest. Was this a miscalculation or a calculated maneuver?

The Payment Default: A Calculated Move?

Speculators never target a country’s banking system alone. The charitable facade of their networks, often made up of hundreds of NGOs and international organizations, conceals broader strategic agendas. The funds these “patrons” channel to NGOs to advance specific political and economic objectives are substantial and far from incidental.

Alongside major global NGOs funded by Soros, new Lebanon-focused organizations have emerged in recent years. Others, founded earlier, shifted their focus to Lebanon after 2017. Between 2019 and 2021, the OSF reportedly provided around $10.5 million to various Lebanese associations. Soros, the Hungarian-born billionaire now succeeded by his son Alex, is notorious for orchestrating speculative financial maneuvers worldwide, including actions that impacted the Bank of England.

Soros has repeatedly mobilized “civil society” to influence or overthrow regimes. Notable examples include Serbia’s Otpor Movement (2000), Georgia’s Rose Revolution (2003) and Ukraine’s Orange Revolution (2004) – all designed to exploit systemic vulnerabilities for profit.

His objectives in Lebanon appear consistent with this strategy: access to hydrocarbons, telecommunications and renewable energy. An intelligence consultant highlights OSF’s indirect involvement in Lebanon’s 2018 parliamentary elections, with Human Rights Watch (also funded by Soros) supporting independent, progressive movements such as Libaladi and YouStink. The consultant also cites a March 2021 study by the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI), whose director, Sean Hinton, is co-director of OSF’s Economic Justice Program and CEO of the Soros Economic Development Fund. The report, focused on Lebanon’s electricity sector, included recommendations on potential gas reserves, in partnership with the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and the American University of Beirut, both connected to Soros’s network.

In practice, OSF carved out a strategic foothold in Lebanon by leveraging “the wave of protests and the crisis of the Lebanese elite,” enabling them to install client institutions, including the NRGI, and advance companies aligned with Soros’s economic interests.

By combining civil society activism with media campaigns, these NGOs exerted pressure on political leaders and international opinion alike, pursuing agendas that served neither Lebanon’s national interests nor its economy. Their influence was so pervasive that the announcement of a sovereign default seemed almost preordained. For example, on September 10, 2018, Daraj, a media outlet launched a year earlier and funded by OSF, published an article titled “What Does Lebanon’s Bankruptcy Mean?,” framing the country’s default as inevitable.

As Lebanon’s crisis deepened, a network of organizations emerged: Minteshreen/Meghterbin Mejtemiin, Endeavor LB, Kulluna Irada, Lebanese International Finance Executives (LIFE), Towards One Nation, ALDIC, Embrace Lebanon, LOGI and the National Bloc. Many shared the same key figures, notably Paul Raphael.

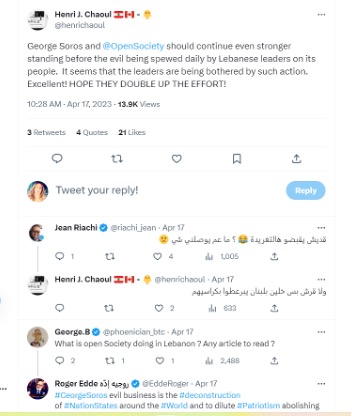

On February 4, 2020, Kulluna Irada urged the government to “fulfill its responsibilities toward the Lebanese people and immediately proceed with a sovereign default,” despite the severe economic consequences such a move entailed. Henri Chaoul, a Kulluna Irada board member, openly defended Soros and highlighted his political influence in Lebanon. In an April 17, 2023 tweet, Chaoul stated, “George Soros and the Open Society should continue even stronger standing before the evil being spewed daily by Lebanese leaders on its people. It seems that the leaders are being bothered by such action. Excellent! HOPE THEY DOUBLE UP THE EFFORT!”

Could the Default Have Been Avoided?

An expert close to the matter told This is Beirut that Lebanon’s sovereign default could have been prevented. Despite multiple alternatives on the table, decision-makers remained committed to the path that culminated on March 7, 2020.

At the time, the Lebanese Central Bank (BDL), which opposed the default, held reserves of around $30 billion and was willing to cover the debt obligations for 2020, 2021 and 2022. Negotiators rejected this proposal, citing a lack of transparency in BDL’s accounts and a broader loss of confidence in the institution.

Postponing payments or restructuring debt to avoid default was feasible. One proposed mechanism, a consent solicitation, would have allowed creditors to grant Lebanon a grace period to negotiate repayment terms and explore debt restructuring. “With mutual agreement from both the Lebanese government and its creditors, the default could have been avoided,” said a financial advisor who opposed the decision, lamenting the authorities’ disregard for this approach.

Under normal circumstances, a state facing default engages in negotiations to secure either partial debt relief or extended repayment schedules. Yet when Diab announced the default, discussions were brief and superficial. “No serious talks were held to explore staggered payments, debt reduction or eased terms,” said a source who participated in the meetings.

The result was catastrophic: the default severely damaged Lebanon’s reputation and effectively barred the country from international financial markets.

What About Hezbollah?

In Lebanon’s confessional system, the presidency is reserved for Christians, the speakership of parliament for Shias and the premiership for Sunnis. When Diab was appointed prime minister, it followed a closed-door meeting between Gebran Bassil, the head of the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) and Nabih Berri, the speaker of parliament and leader of the Amal Movement – both allies of Hezbollah. Notably, Diab assumed office without the support of the Sunni community’s primary representative, former Prime Minister Saad Hariri.

Supported by Hezbollah, one of the principal beneficiaries of the default, Diab took office on January 21, 2020. Two months later, he announced Lebanon’s historic suspension of debt payments, a decision that shattered what remained of the country’s fragile social and economic balance.

Since then, Hezbollah’s parallel economy, built on revenues in US dollars while operating within a collapsed Lebanese pound, has flourished. A source told This is Beirut that the group’s monthly revenues are estimated at around $100 million. While Hezbollah has remained silent on the matter, data from the US Rewards for Justice program supports this figure, estimating that the organization earns nearly $1 billion annually through direct Iranian funding, international business ventures, donor networks, corruption and money-laundering activities.

The calculation is straightforward: the Lebanese pound has lost over 98% of its value.

Attempted LBO?

When Lebanon announced on March 7, 2020, that it would default on its debt, some political and economic circles saw the move as a calculated strategy to acquire the country’s assets at bargain prices – metaphorically, a leveraged buyout (LBO). While the term traditionally refers to acquiring private companies with borrowed funds, could the same logic apply to nations, and Lebanon in particular?

For years, Beirut has appeared caught in a cycle that goes far beyond a typical economic crisis, resembling a state-level leveraged buyout. The logic is straightforward: acquire a weakened asset through debt, restructure it, extract its value and sell off strategic components. By 2019, the conditions for such a scenario were fully in place: unsustainable public debt, a declared default, a collapsed currency, a drained banking system, a state incapable of investing and reliant on foreign lenders, chronic political instability and dysfunctional institutions. Yet this fragility existed alongside strategic assets, making Lebanon an attractive target for potential “buyers.”

Offshore hydrocarbons exemplify this dynamic: TotalEnergies, ENI and QatarEnergy have secured exploration blocks, while investment funds such as Carlyle and Blackstone are targeting the Eastern Mediterranean as a strategic asset within the global energy landscape. Lebanese real estate, particularly along the coast, along with key public sectors like telecommunications, electricity and water, are highly coveted assets, potentially suitable for public-private partnerships or partial privatization. The Lebanese diaspora adds another unique lever, contributing both financial resources and human capital.

The financing of this “state-level LBO” was already underway. The World Bank and IMF tied their aid to reform programs, while the European Union structured its support around refugee management and border stabilization. International consulting firms, including McKinsey, Boston Consulting and Roland Berger, helped design strategic roadmaps and restructure state institutions. At the same time, private financial institutions were preparing reconstruction funds as targeted investment vehicles, and technology and security companies – such as Palantir and USAID-backed agencies – implemented frameworks for strategic risk and data management.

A state-level LBO follows a predictable sequence and Lebanon appears to be on this trajectory. Step one: stabilize. Forge a political compromise, restore the presidency, prevent open conflict and implement minimal institutional reforms. Step two: reform. Introduce property laws, lift banking secrecy, restructure public sectors and provide assurances to investors. Step three: extract value. Develop offshore resources, establish free zones, promote public-private partnerships and leverage the country’s strategic location. Step four: divest or integrate. Incorporate Lebanon into a regional gas project, place it under indirect international oversight or partially absorb it into a larger economic bloc. The blueprint mirrors that of a distressed company, scaled up to the national level.

Weakened and fragmented, Lebanon now resembles an undervalued asset teeming with potential, where the logic of a leveraged buyout envisions a future in which its resources, infrastructure and human capital are reorganized to serve external interests. The question is no longer whether the country can recover on its own, but which financial, energy and geopolitical actors will take control of its strategic assets and steer its restructuring. Behind the state’s collapse lies the blueprint of a global financial scheme, with sovereignty reduced to its ultimate bargaining chip.

Comments