The upcoming parliamentary elections are highly important, marking a defining moment in Lebanon’s history. Since independence, the country has held many elections, each shaped by its own circumstances. Some of these elections have stood out as true turning points, reshaping Lebanese politics and strengthening the balance of power in the country.

For instance, the 1968 elections reflected the aftermath of the 1967 defeat and the decline of Gamal Abdel Nasser, along with the weakening of his Lebanese ally, Fouad Chehab. Key figures of the Chehabist movement were defeated by the then-dominant tripartite alliance, creating a new political balance in Lebanon.

In 2005, the international community insisted on holding the elections as scheduled, capitalizing on the momentum from street protests in Lebanon following the assassination of Prime Minister Rafic Hariri and the uprising against the Syrian army. However, it first faced resistance from the Shia community, which demanded strict adherence to the law, fearing that Hezbollah and the Amal Movement could have their political legitimacy undermined.

Moreover, the international community faced a second challenge in the Christian areas following Hezbollah’s formal entry into the government after the Syrian withdrawal. Michel Aoun’s tidal wave generated a notable degree of unpredictability in the streets, particularly after an agreement was signed with Hezbollah a year later.

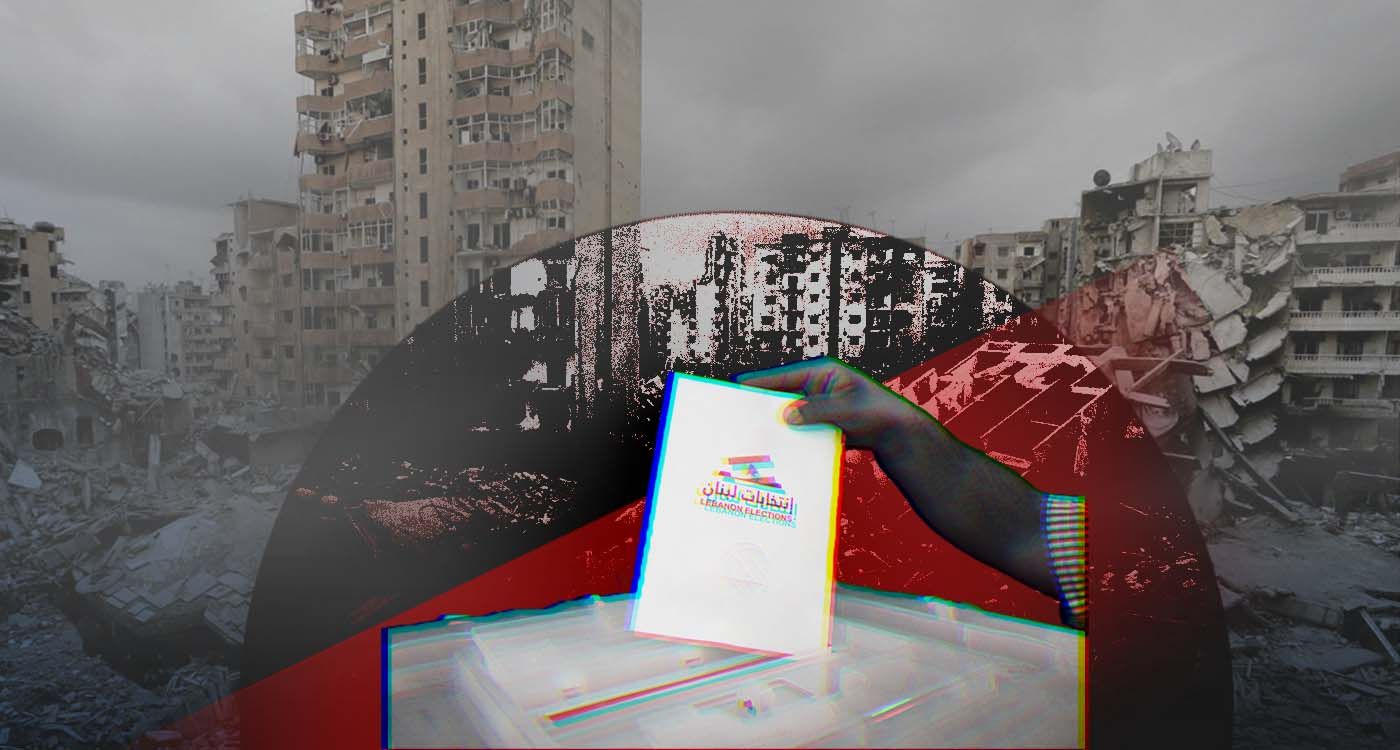

The 2026 parliamentary elections – if they are held on time – are among those pivotal elections that carry not only popular significance but also profound political symbolism. Each of the existing parties continues to wield considerable influence and the capacity to assert its terms and shape Lebanon’s political landscape.

These are the first elections since the 2024 war against Israel that curtailed Hezbollah’s influence – though the group itself would reject that label. It is now clear that its role on the domestic stage has been largely reduced to symbolic gestures, such as lighting a rock or organizing a scout ceremony, whereas in the past it had the power to topple governments and dictate political settlements in Beirut.

Against this backdrop, the defining challenge of the next phase will be breaking the Shia monopoly, though this will be no easy task. Genuine Shia opposition is virtually nonexistent, and electoral support for the Amal-Hezbollah duo is expected to remain firmly entrenched.

Even if a Shia candidate were to break through in any district, they would not be able to assume the position of Speaker of Parliament, as they would lack genuine Shia legitimacy. Such a scenario could mirror what the Christian community experienced in 1992 and the years that followed, when Michel Aoun returned to Lebanon stronger than he had been before his exile.

All of these factors suggest that the real challenge after the elections will come down to one of two options. The first is reinstating Nabih Berri – or a successor of similar stature – as Speaker of Parliament under the conditions set by Amal and Hezbollah. Paradoxically, this could help manage interactions with the duo, especially considering the Speaker’s role in navigating crises and maintaining balance and consensus in Lebanon.

The second option is to dismantle the Amal-Hezbollah tandem in Parliament, which would thrust the Shia community into a situation reminiscent of what the Christian community experienced after the Taif Agreement, and what the Sunni community faced during the ouster of Saad Hariri.

The upcoming parliamentary elections are poised to mark a decisive moment, no less consequential than the last war. A postponement, however, may be politically prudent until the aforementioned political settlement is fully established; otherwise, holding the elections could spark constitutional and legal challenges even more intricate than the current deadlock.

Comments