- Home

- Middle East

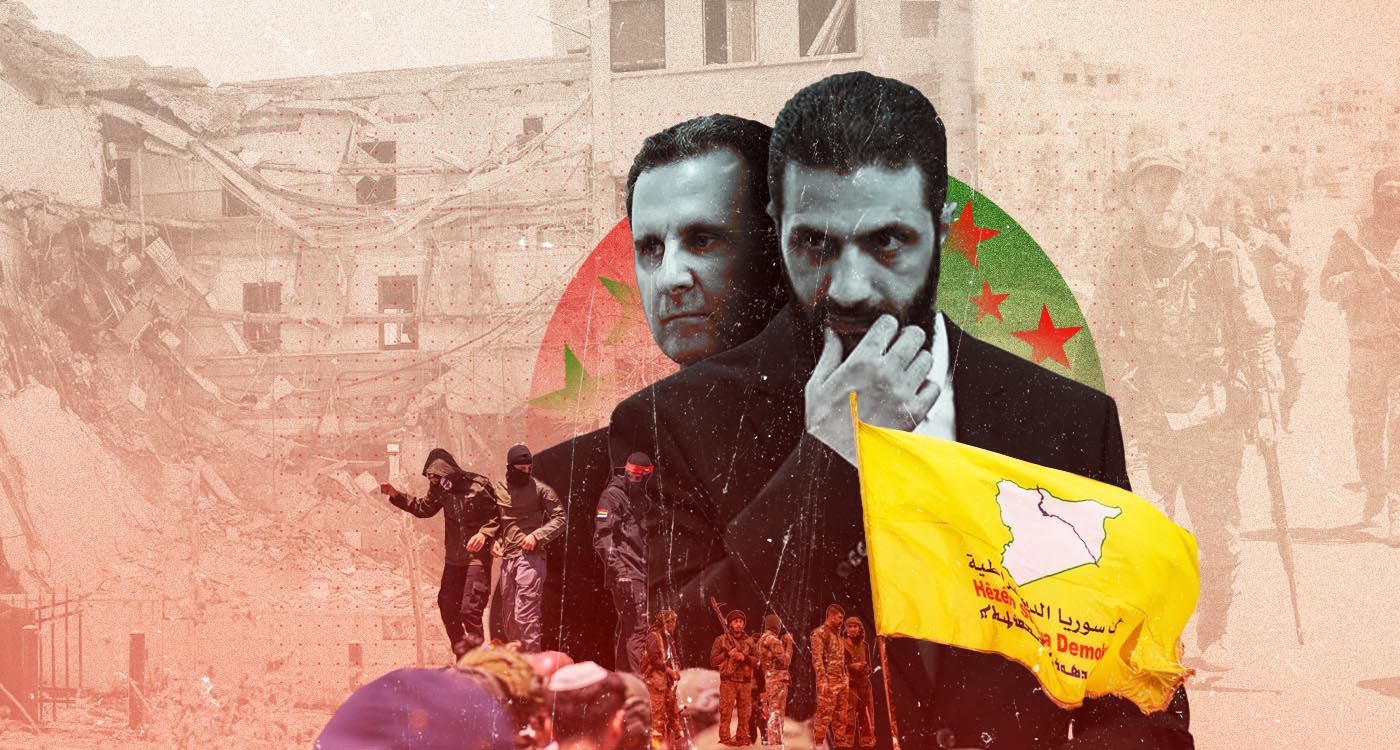

- Assad Is Gone. The Syrian Problem Persists

©This is Beirut

Nine months after Bashar al-Assad's fall and Ahmad al-Sharaa's rise to power, the UN Security Council met to address Syria’s ongoing crisis. The Council urged Damascus to establish a government “of the Syrians, by the Syrians, for the Syrians.” Despite the change in leadership, the Security Council views Syria as a failing state. Damascus must implement UNSCR 2254 and dismantle the Islamist monopoly on power.

History shows that without a major power enforcing its resolutions, the Security Council’s decisions are toothless. In the Middle East, and Syria in particular, only the United States has the influence to effect change. Yet US Envoy Tom Barrack appears enamored with Sharaa’s Islamist regime in Damascus.

While the world watches Sharaa’s forces massacre Alawites on the coast, Druze in the south, and potentially Kurds in the northeast, Barrack extols the virtues of a revived Ottoman Empire, with Damascus as its crown jewel. He defends Sharaa’s regime, claiming that atrocities against the Druze were committed by Islamists disguised in government uniforms. Overwhelming evidence—security camera footage and confessions from Sharaa’s captured fighters—debunks this claim. Damascus is complicit in these war crimes.

With America unwilling to curb Sharaa’s autocratic ambitions, no one can enforce UNSCR 2254. Sharaa pretends to build a new, progressive Syria while constructing a formidable autocracy, ruling with the same fire and fury as the Assad dynasty.

Last week, Syria’s Kurds held a conference in their de facto autonomous region in the northeast, inviting representatives from all ethnic and religious groups. Their goal: to demand local governance east of the Euphrates, free from Damascus’s centralized control. They believe decentralization better serves Syria’s future.

Sharaa, however, views such ideas as a challenge to his vision of undisputed, autocratic rule. In retaliation, he ordered his delegation in Paris to boycott talks with the Kurds aimed at resolving disputes. Under Sharaa, dissent is punished as it was under Assad.

Like his predecessor, Sharaa has cultivated a network of shabbiha—thugs who enforce his will and silence opposition. To his supporters, Sharaa is the new Umayyad Caliph, whose orders are absolute.

Less than a year after Assad’s downfall, the Syrian revolution—fueled since 2011 by millions of Syrians and their friends like myself—feels betrayed.

When Assad fell on December 8, Sharaa claimed he had no interest in becoming president, insisting all revolutionaries were equal. Six days later, I wrote him an open letter, urging him to run for president, spread liberty, and step down after his term to set a democratic precedent, as George Washington did in early America.

I held no illusions that Sharaa was Washington, but his promises of change warranted cautious optimism. Yet, as many feared, Sharaa has revealed himself as another dictator-in-the-making. Hudoud, the Arabic weekly satire publication, the equivalent of The Onion, captured it perfectly: “Sharaa declares himself Hafez Assad.”

In his theater of “transitional power,” Sharaa has amassed more authority than both Assads combined. There are no deadlines for a constitution or elections. Any future constitution or vote will likely serve to legitimize his Islamist autocracy, just as Assad’s did.

George Orwell’s Animal Farm offers a fitting parallel. After overthrowing the negligent farmer, the pig Snowball declared all animals equal. Soon, the constitution was amended: “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.” This now describes Sharaa and his former revolutionary comrades. One day, even his Islamist allies may face purges. This is a familiar story, replayed across Arab nations since the mid-20th century’s end of empires.

With America’s inaction likely to spark regret in years to come, Syria’s neighbors are left to fend for themselves.

Lebanon must disarm Hezbollah and rally behind its national army. Its porous border with Syria risks spillover from ongoing turbulence or renewed conflict.

Israel has little choice but to continue airstrikes to police Syria, as it does in Lebanon. Sharaa pledges to honor the 1974 ceasefire, as Assad did for decades, but there’s no guarantee he will comply—or remain in power long enough to do so.

Iraq, too, faces spillover risks, much like Syria. The Islamic State ISIS once spanned both countries, and similar threats could resurface.

Jordan must stay vigilant against destabilizing trends from Syria, including the flow of Captagon drugs, Islamist militias, and other disruptive forces.

Continued UN Security Council meetings to discuss Syria mean the problem persists, even after Assad’s fall.

Read more

Comments