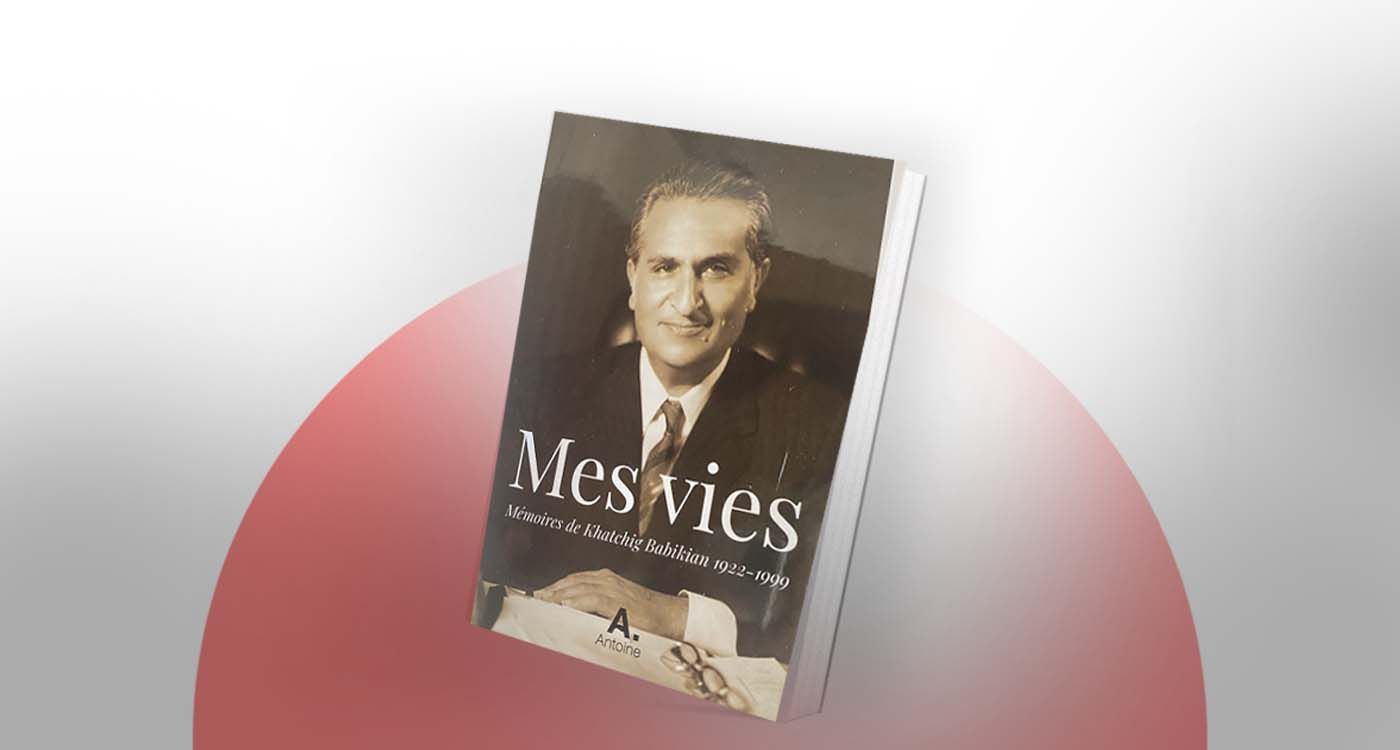

Christine Babikian Assaf presents My Lives, the edited and annotated memoirs of her father, Khatchig Babikian (1922–1999).

Christine Babikian Assaf offers us an unfinished yet invaluable work: the Memoirs of her father, Khatchig Babikian—a towering figure of Lebanese parliamentary history in the 20th century and one of the key architects of the Taif Agreement. Published under the title “My Lives”, this book is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand Lebanon’s history during the latter half of the 20th century. Beyond intimate recollections of his youth, it offers crucial insights into the political maneuvers and turning points that shaped a critical and painful era of the nation’s life.

This carefully composed text is not a historical paper, but rather the portrait of an era, seen through the eyes of a singular witness. Written at the behest of his family, it stands as a final act of remembrance for a life richly lived—hence the title My Lives. It is the testament of a man deeply grateful for the many opportunities he had to give his best in service to both his community and Lebanon as a whole.

Left unfinished due to exhaustion—by a man who never did anything halfway and who had reached his limits—the manuscript has been lovingly completed, annotated, and enriched with photographs and testimonies by Professor Christine Babikian Assaf. An especially important appendix offers Khatchig Babikian’s forward-looking vision for Lebanon and its youth, titled Lebanese Youth and the Future Vision of the Lebanese State.

Born in Cyprus

The book traces the key chapters of a life that began in Cyprus, where his parents had sought refuge after being uprooted from Cilicia. Babikian himself experienced displacement while attending the Italian school in Beirut. But during his law studies at Saint Joseph University, he forged a strong and multifaceted identity, which would serve him well both in his career as a lawyer and in his long public life as a parliamentarian and minister.

He carried this profound sense of duty into his work with the Catholicosate of Cilicia (Antelias), his commitment to the most vulnerable in his community, his engagement with the wider Francophone world—as reflected in his memoirs, written in French—and his leadership role in the Lebanese Management Association. Thanks to his renowned versatility, Babikian managed nearly every ministerial portfolio over his career: from Administrative Reform, his true passion, to Economy, Justice, Health, and Tourism. A man of both heart and principle, his legacy endures through a scholarship fund at Saint Joseph University and the Khatchig Babikian Foundation, entrusted to the Catholicosate of Antelias.

His life—one of relentless work and sleepless nights—was also marked by deep personal tragedy, notably the premature loss of his beloved wife Margot, mother to his five daughters, with whom he shared a deep and generous love story.

A True Fusion of Two Identities

Khatchig Babikian was the epitome of harmony between Lebanese and Armenian identities. Deeply committed to mastering Arabic after Lebanon’s independence—when French was removed from legal proceedings—he even memorized entire surahs of the Quran. His command of Arabic earned him respect in courtrooms, parliament, and among audiences across the country.

As a proud Armenian, he also embodied the spirit of enterprise and creativity that characterizes his people, dedicating himself wholeheartedly to every area under his ministerial purview. Yet, as his daughter recalls, he discouraged his children from dwelling on old photo albums or nostalgia. Instead, he focused on the present and future—embracing activities like Swedish gymnastics and management science (what today would be AI).

Politically, Babikian’s life was closely aligned with the Tachnag Party, the leading Armenian faction in Lebanon, which played a key role in maintaining cohesion in the aftermath of the 1915 genocide. Under its banner, he won his first parliamentary seat in 1957—a position he would honorably hold for 40 years.

Another significant political relationship was his affinity with President Fouad Chehab. The two shared a deep commitment to statehood, reform, and a rejection of favoritism. Yet, just as Lebanon was building the democratic foundations essential to sovereignty, external forces—including Palestinian, Syrian, and later Iranian influences—emerged to strip the state of one of its most fundamental powers: the monopoly on arms. This challenge to Lebanon’s sovereignty persists to this day.

External Causes of War

Nowhere in Babikian’s memoirs does one find the phrase “civil war.” Yet, between the lines, it becomes clear that social inequalities, often cited as the root cause of Lebanon’s collapse, were far less significant than the external pressures: the armed Palestinian presence that had “held the Sunni community hostage” (p. 159), and Syria’s insidious and destabilizing interventions.

During war years, which he did everything in his power to prevent, Babikian narrowly escaped death multiple times. On one occasion, he chose to avoid the Basta route to Achrafieh—where Christian drivers were being beheaded or shot (p. 157)—opting for a safer alternative. On another, his bodyguard and driver saved him from a threatening crowd in Anjar—a town built largely by Armenians but coveted by nearby tribes aiming to seize its properties.

In the end, Khatchig Babikian succumbed to illness.

A book not to be missed.

Comments