If you want to understand the Middle East in 2025, don’t look at the maps. Look at the fault lines. They’re not drawn in ink – they’re drawn in fear, legacy and a deep unease that this time, the region isn’t just shifting, it’s splintering.

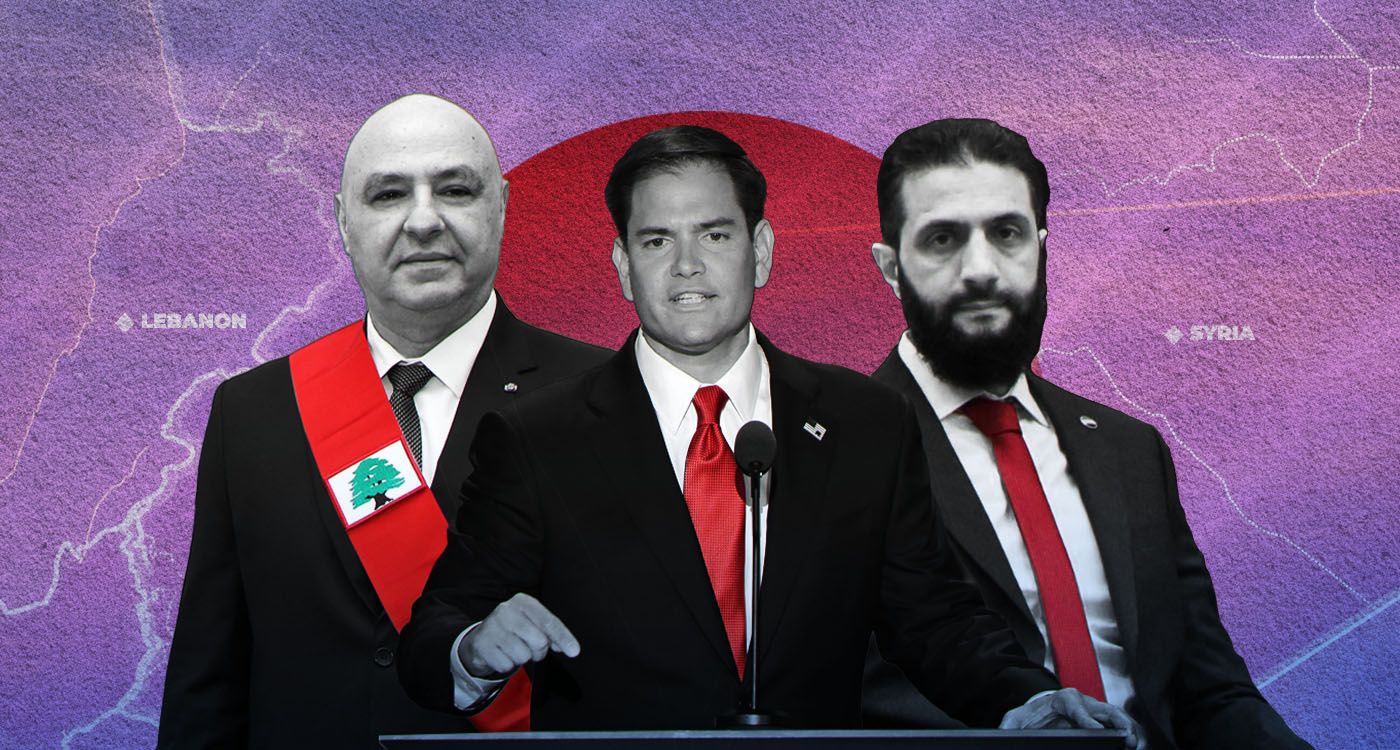

This week, United States Secretary of State Marco Rubio sounded an alarm loud enough to rattle the glass in every foreign ministry from Beirut to Berlin. Syria’s transitional government, led by President Ahmed al-Chareh – who rose from the ashes of Assad’s collapse – is, according to Rubio, “weeks away” from implosion. Not months. Not quarters. Weeks. It also could be that, as is often the case in Washington, getting Congress to act sometimes requires amplifying the problem first.

The urgency of his words isn’t just about Syria. It’s about what Syria’s collapse would catalyze across the region: a reignition of a civil war that doesn’t end in victory or defeat but in something more complex, and potentially more permanent: federalism, fragmentation and the official carving up of Syria into confessional enclaves.

This begs the question: Is this fragmentation a bug – or a feature?

President Donald Trump, in a rare pivot to international restraint, temporarily lifted US sanctions on Syria for 180 days, a tactical decision designed to prop up the transitional government, give breathing room for local actors, and signal that Washington isn’t ready to watch Damascus burn – again. But Rubio’s timing was intentional, not coincidental. He wasn’t just giving Syria a warning; he was sending Lebanon a memo.

You see, America’s dual policy – carrot for Syria, cold shoulder for Lebanon – isn’t accidental. The US is trying to manage the post-Assad vacuum by empowering a “moderate transitional force” in Damascus, while subtly warning Beirut’s elite that time, patience and international goodwill are wearing thin.

And while this may sound like another predictable cycle of Western diplomacy in the Levant, it’s more than that. It’s a soft pivot in strategy that implicitly serves an unspoken regional doctrine: Israel’s long game.

Let’s not kid ourselves – Israel has no appetite for a fully restored, unified and militarized Syrian state. A fractured Syria, segmented into Kurdish, Alawite, Druze and Sunni entities – none powerful enough to pose a threat across the Golan – is a de facto buffer zone. It turns Syria from a threat into a security quilt stitched together by mutual suspicion and foreign influence.

And here’s where it gets real: US policy, knowingly or not, is inching in that direction.

Supporting a transitional Syrian government that lacks the capacity to govern the entire country doesn’t prevent division – it accelerates it. Lifting sanctions is not an endorsement of unity – it’s a stay of execution. The outcome? A potential Syrian “Dayton Accord” moment: one country, many cantons, none dominant. For Israel, that’s not just acceptable – it’s optimal.

Now pivot your gaze west, to Lebanon.

Lebanon’s government is on a ticking clock. Lebanon still enjoys US attention, but it’s conditional. If Lebanon doesn’t reform, stabilize, and detach from the dead weight of regional proxies, it risks slipping off Washington’s radar – and onto the list of “manageable instability.” That’s diplomatic code for: “We’ll call you if we need you.”

The tragedy? Lebanon, unlike Syria, hasn’t yet collapsed. It still has institutions, a civil society and geopolitical relevance. But its leaders are playing 1980s chess in a 2025 AI world. Syria is being redefined, borders are being renegotiated – metaphorically if not legally – and Lebanon is still arguing over ministerial seats and obsolete power-sharing formulas.

Here’s the strategic blind spot: if Syria breaks into manageable statelets, Lebanon’s geographic and demographic coherence becomes a liability – not an asset. A strong Lebanon bordering a weak Syria used to mean strategic leverage. But a fragmented Syria next to a fragmented Lebanon? That’s a recipe for spillover, not strength.

So what should President Joseph Aoun do about Hezbollah? The answer isn’t as simple as a call for disarmament – it’s about timing, leverage and reframing. Direct dialogue with Hezbollah may project national unity, but history shows it rarely produces real results. Instead, Aoun should shift the conversation: it shouldn’t be about eliminating weapons overnight, but about restoring the state’s monopoly over military decisions, particularly on matters of war and peace. That’s a sovereignty issue, not a sectarian one. At the same time, he must capitalize on the rare alignment of US support, EU interest and Hezbollah’s own regional vulnerabilities – caused by a weakening Syria and a stretched Iran. Now is the moment to propose a credible national defense strategy, backed by international guarantees, that slowly reintegrates Hezbollah’s military role into the state structure – or exposes their refusal to do so. Most importantly, Aoun must rebuild the strength of the state itself: empower the army, secure the judiciary, and channel international aid into real institutional reform. Because the only way to disarm a militia with mythic power is not just through pressure – but by making the state strong enough that myths are no longer needed.

Recognize that America’s current backing is not a blank check. It’s a bridge – and bridges collapse when no one maintains them.

Because when a region starts drawing its future in sand, the countries that don’t move quickly enough get buried under it.

Comments