The Star of David can be seen in several churches in Mount Lebanon. Its presence in Christian buildings should not be surprising. For Maronites, it represents their Old Testament heritage and the continuity between the Old and New Testaments.

A large number of old churches and chapels in the Lebanese mountains feature the Star of David, engraved on keystones, spandrels, cornices, and even doorframes. In some cases, this motif also appears in private homes whose ornamentation draws inspiration from religious architecture.

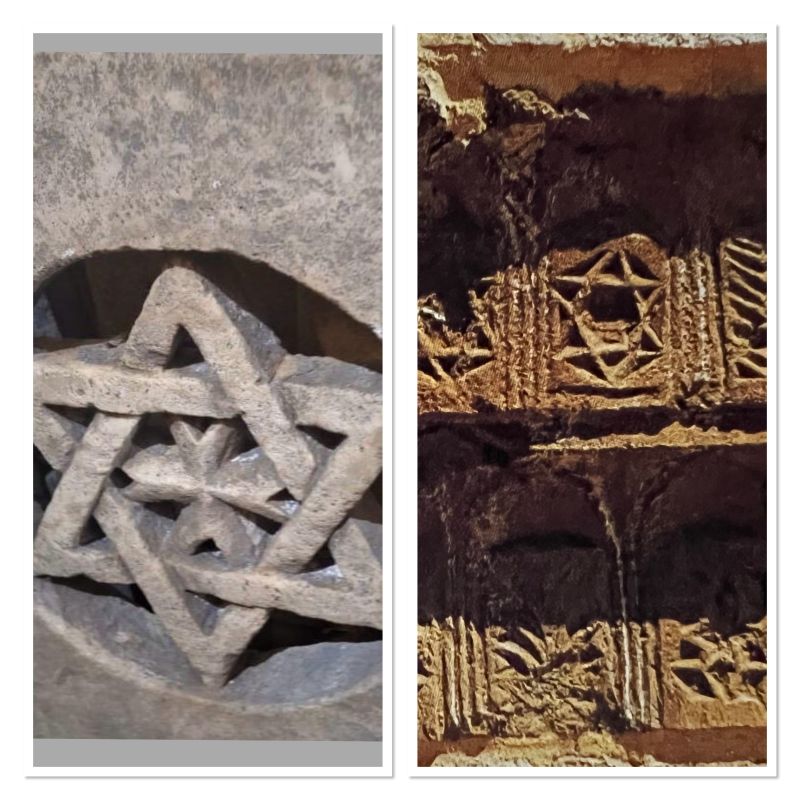

The star appears in various forms – sometimes on its own, sometimes with a cross inscribed within it or even carved beside it. It can be sculpted in relief, engraved in hollow, or even in an openwork design that allows for ventilation and filtered light. In Jewish tradition, the interwoven triangles symbolize the connection between the inner and outer dimensions of Yahweh. The presence of this Jewish symbol on Christian buildings is hardly surprising. For Maronites, it represents their Old Testament heritage and reflects the continuity between the Old and New Testaments.

Brichit

It all begins with the Brichit, the origin of everything. In Judaism, Genesis states, “Berechit bara Elohim ét ha-chamaïm vé ét ha-arets.” (“In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.”) For the Maronites, the Gospel of Saint John reads, “Brichit itawo Melto.” (“In the beginning was the Word.”)

The resemblance goes beyond linguistics. There appears to be a deliberate effort to embody this heritage through the choice of vocabulary. In fact, even in the Syriac version of Genesis, we observe the use of the distinctly Hebrew article “ét,” which is redundant in Syriac. This is particularly evident in the form “iot chmayo,” which corresponds to the Hebrew “ét ha-chamaïm” (the heavens).

“In the beginning was the Word;” this sentence is the foundation of Jewish and Syriac artistic expression, particularly within the Maronite tradition. Both imagery and script serve as representations of a world at the heart of which lies the Word. The illuminated letters in Latin or Armenian scripts are unimaginable in Hebrew and Syriac writings, except in certain Jewish manuscripts from Europe. The virtuosity of arabesques and geometric patterns in Arabic calligraphy also appears as a barrier to the approach of the divine, as understood in both Judaism and Syriac Christianity.

A cross is inscribed within a Star of David with interwoven triangles (left) and a Star of David with interwoven triangles in a manor house in Baskinta (right).

Script and Imaging

A close look at Maronite churches shows that regardless of the richness of the carved stone decoration surrounding a Syriac inscription, the letters remain austere. As an heir to Old Testament writing, it seeks to express the Word-Melto. The script rejects formalism, and any addition is considered superfluous and removed from the truth. At its core, the writing strives to maintain its acheiropoietic nature, meaning it is not created by human hands.

Christianity thus completes Judaism. It claims to be its legitimate heir, and this is evident in its frescoes and miniatures. In the medieval Maronite church of Saint Theodore in Béhdidét, the apse is adorned in its upper section with scenes from the Old Testament. Among them are Abraham, Isaac, the sacrificial lamb, and Moses receiving the tablets of the Law. Below, there is the scene of the Deesis, with Christ in glory, the Mother of God, the archangel and the cherubim.

Read also: https://www.maronitas.org/post/los-frescos-medievales-del-l%C3%ADbano-1-2

These juxtaposed themes reflect an iconographic tradition adopted by all churches, whether Catholic or Orthodox. They were already established in the 6th century, as evidenced by the Maronite Gospel Book of Raboula. On each of its arcade folios, the upper part of the composition depicts scenes from the Old Testament, while lower down, episodes from the life of Christ are portrayed.

Read also: https://thisisbeirut.com.lb/a1304238

Star of David is set upon mandalouns of two manor houses in Beit Mery.

The Maronite Mass

Heritage and continuity are also powerfully reflected in the Maronite Mass, where prayers and hymns draw from the Psalms of the Old Testament at the start of each of the two parts of the celebration. A psalm is called “mizmor” in Hebrew and “mazmouro” in Syriac, both derived from the verb “zamar” (to sing). Maronite liturgical texts leave no ambiguity about the origins and identity of this tradition, explicitly titling them: Psalms of David, King and Prophet.

The first part of the Maronite Mass is when the celebrant breaks the Word (Qosé l’Melto), which amounts to proclaiming the word of the Lord. This phase begins with the verse (Ps. 5:7):

L’vaytokh Aloho élét wa qdom bim dilokh segdét, malko chmayono haso li kol da htit lokh.

I will enter your house, O Lord, and bow down in your holy temple (Ps 5:7); Heavenly King, forgive me all my sins.

During the second part of the Mass, the celebrant breaks the bread (Qosé l’lahmo) and leads the congregation into the Eucharistic consecration. He then returns to the Psalms, chanting the verse (Ps 43:4):

Ité lwot madebhé d’Aloho, wa lwot Aloho da mhadé talyout.

I go to the altar of God, to God who gives joy to my youth.

He then continues with the verses (Ps 5:8-9):

W’éno b’sougo d’tayboutokh éoul l’vaytokh w’ésgoud b’hayklo d’qoudchokh.

But as for me, upheld by the multitude of your mercies, I will enter your house; I will bow down, facing your sanctuary, filled with your fear. Lord, guide me in your righteousness.

Literature and Hymns

The most emblematic phrase of the Maronite Church, which appears on its coat of arms, is also borrowed from the Old Testament. It echoes Isaiah: Iqoro de Lévnon métihév léh (The glory of Lebanon is given to him. (Isaiah 35:2)). This phrase adorns the pediment of the patriarchal monastery of Bkerkeh in magnificent Estrangelo square letters.

We should also recall that the Syriac protective formula, linked to their most sacred symbol, the cross, is yet another quotation from the Psalms, with the verse (Ps 44:6):

Bokh ndaqar la beeldvovayn, w métoul chmokh ndouch l’sonayn.

This inscription appears again in the Middle Ages, on the crosses of Saints Serge and Bacchus in Ehden (1188), of Our Lady of Ilige (1276), and in the 18th century at Saint Doumet of Zouk-Mikhael and Saint Elie of Jeïta.

The relevance of King David is further highlighted by the hymn sung on Palm Sunday, which draws from the Gospels of Saint John and Saint Matthew:

Ouchaano la bréh d’Dawid

Ouchaano l’malko d’Isroël

Hosanna to the Son of David (Mt 21:9)

Hosanna to the King of Israel (Jn 12:13)

The hymn that accompanies the entrance of the Maronite patriarch, or sometimes the bishop, into the church is also an Old Testament legacy, specifically the psalm (Ps 147:12):

Chavah Ourichlem l’Moryo

Chavah l’Aloékh Séhion

Glorify the Lord, O Jerusalem,

Praise your God, O Zion.

Syriac Theology

The concept of continuity with the Old Testament goes beyond the mere adoption of literary formulas from Scripture. For the Syriacs, it has deeper significance and defines the very essence of their religion. According to Father Tanios Bou Mansour, for Saint Jacob of Sarug, “continuity with the Old Testament reflects a deeper connection between the action of the Son and that of the Father.” Father Bou Mansour also refers to Saint Ephrem, who wrote in the fourth century that the Father and the Son are formed within each other, which is why they are also formed within Scripture and Nature, which together constitute our world.

In his ecological vision, so characteristic of the Syriacs, Saint Ephrem is even more explicit when he describes the Old Testament, the New Testament and Nature as three harps. He sees the Church as their creation, inseparable from them, as rejecting them would mean rejecting itself.

Your finger (O Church) plays upon the harp of Moses,

Of our Savior, and of Nature.

Your faith sings of the three,

For the three have baptized you.

With only one name, you could not have been baptized.

Comments