From the overall composition to the smallest marginal vignettes, as well as the portrayal of the apostles, the Codex Rabulensis codified the models of Christian imagery and defined its iconographic canons.

The Codex Rabulensis, a Syriac Maronite manuscript from the year 586, laid down — or codified — composition and representation models that would be adhered to until the Renaissance. Its importance stems not only from its precise date, which serves as a reference for other Christian manuscripts, but also from its role in establishing the iconographic canons of the Christian world.

The Physical Characteristics

This manuscript defined the physical characteristics of the apostles, which would later be found in the Middle Ages, in the churches of Lebanon and across the Christian world. Mark and Luke are depicted in the prime of life, while Matthew is portrayed as an elderly man, writes Jules Leroy. Thus, the Rabulensis stands as the oldest witness to an iconography that would continue into the 10th century, in the art of Armenia and its neighbor, Georgia.

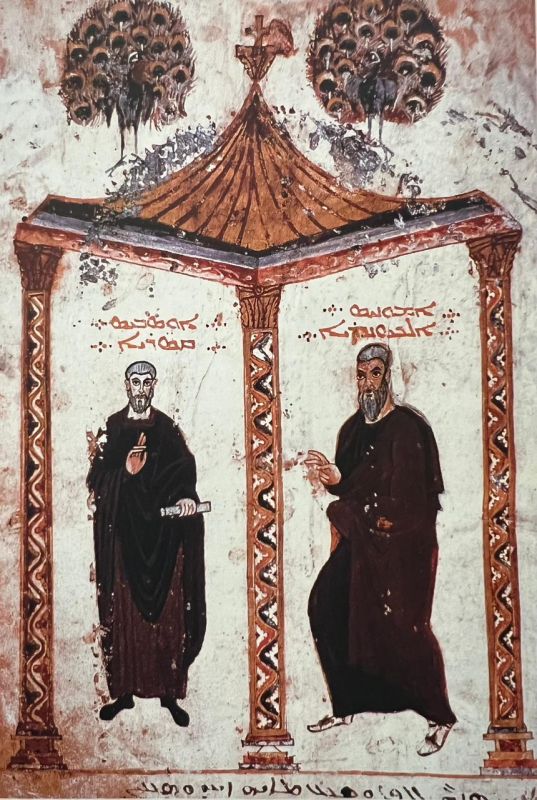

In 12th-century Lebanon, at Saint Theodore of Behdidat, we still see Mark in the prime of life and Matthew as an elderly man. Both are framed by arches on columns, with their names inscribed vertically in Syriac within their halos. The apostles depicted in this church are haloed, imparting a Christian, hieratic aura. However, in the Codex of Rabula, some seated figures retain classical postures inherited from Roman antiquity.

Thus, in this manuscript, there is a juxtaposition of the Christian and pagan worlds. Some figures are rendered in a Christian style, while others, dressed in Roman togas, retain a distinctly pagan posture. In addition, we notice an artistic revolution that eliminates the third dimension to incorporate a two-dimensional, timeless spiritual realm. In keeping with Christian values, the heritage of the past is not discarded but reimagined, infused with new significance.

The Symbolism

Christian symbolism is remarkably rich, drawing from an extensive iconographic repertoire inspired by the pagan world. It encompasses a wealth of animal and plant imagery that depicts the life of Christ through a process of Christian transposition of ancient pagan symbolism.

As Jules Leroy explains, the rooster symbolizes Saint Peter’s denial through a method of abbreviation frequently seen in Armenian manuscripts, where a part stands for the whole. Similarly, and using the same approach, the lamb represents the Good Shepherd. The stag, whether shown alone or drinking from a spring, evokes the words of Psalm 41: "As the thirsty deer longs for flowing water streams, so my soul longs for you."

The dove embodies a variety of symbolic meanings. It sometimes represents the Holy Spirit and at other times symbolizes spiritual renewal. In other contexts, it recalls the story of the Flood (Gen. 9:8) or Christ’s baptism (Matt. 3:16). The pagan motif of the ibis fighting the serpent is a reference to Christ’s triumph over the forces of death. Finally, the basket of bread or fruit alludes to the Eucharistic worship.

While these illustrations summarize the life of Jesus and align with the text, the scattered plants and birds, arranged seemingly at random within the composition, lack a clear narrative purpose. This practice evokes a pagan tradition of adorning Phoenician or Roman tombs and funerary chambers with earthly motifs designed to enliven the space and evoke life. We can observe echoes of this custom in Lebanese architecture from the 18th and 19th centuries, both in sculpture and mural painting.

The Large Compositions

In addition to text-filled pages written in magnificent estranguélo script and the folios of the Tables of Concordance, the Rabulensis includes compositions that rival the artistry of fresco painting. There are seven in total: the depiction of the Virgin (folio 1 V°), the election of Matthias (folio 1 R°), Ammonius and Eusebius (folio 2 R°), the Ascension (folio 13 V°), the Crucifixion and Resurrection (folio 13 R°), Pentecost (folio 14 V°) and Christ enthroned (folio 14 R°). These scenes also offer insights into the aesthetic principles underlying their composition.

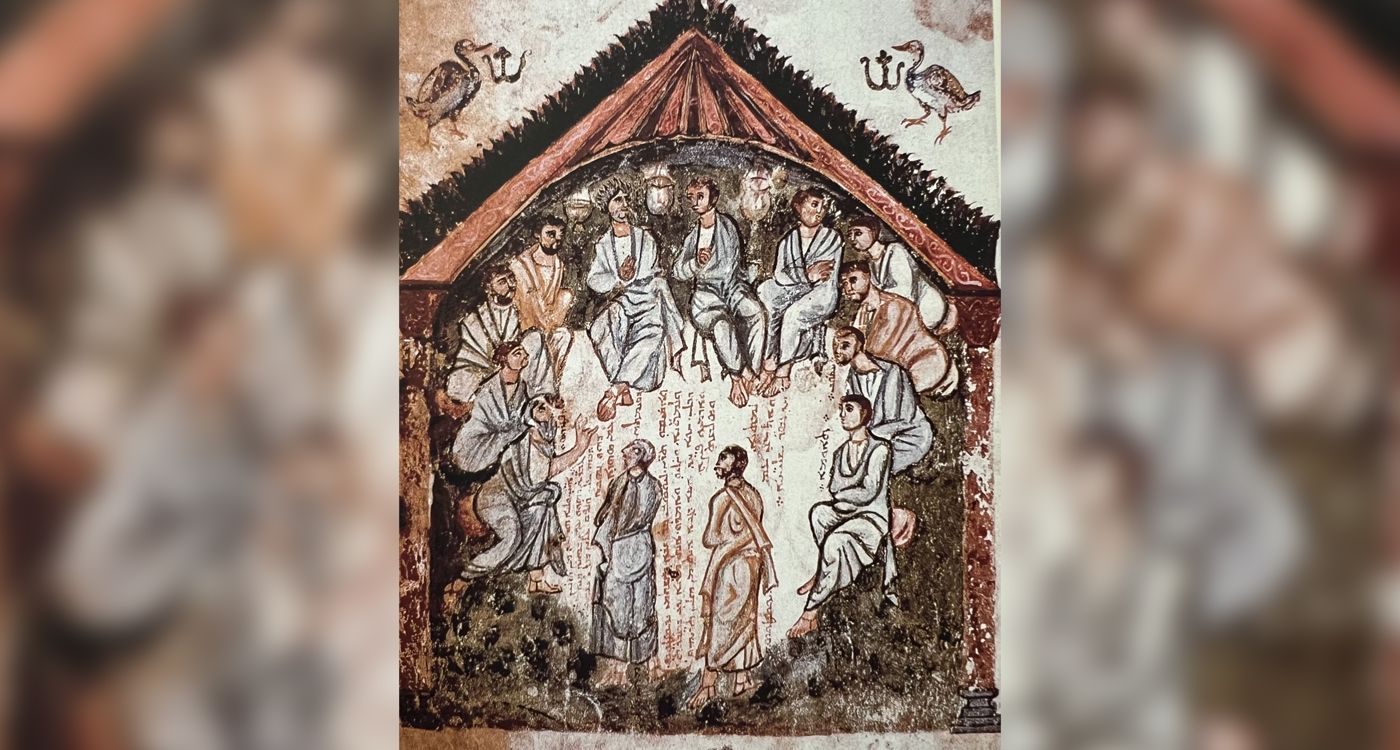

For the election of Matthias (folio 1 R°), a temple formed by natural elements can be seen, with green symbolizing the earth and a blue arch representing the sky. This arch is crowned by a pediment supported by heavy columns, in contrast to the lightness of the arcades in the Tables of Concordance. The apostles, dressed in Roman fashion and without halos, are arranged in a circle, each accompanied by their name written vertically in Syriac estranguélo, just like the main text.

The composition depicting Ammonius and Eusebius (folio 2 R°) is identical to that in the Tables of Concordance. However, it replaces the twin arcades with a triangular canopy, also flanked by birds: two magnificent peacocks. Ammonius of Alexandria turns to the left to converse with Eusebius of Caesarea, who holds a scroll of parchment. These two figures are the first to have compiled the four gospels into a single gospel book.

Two-tier Compositions

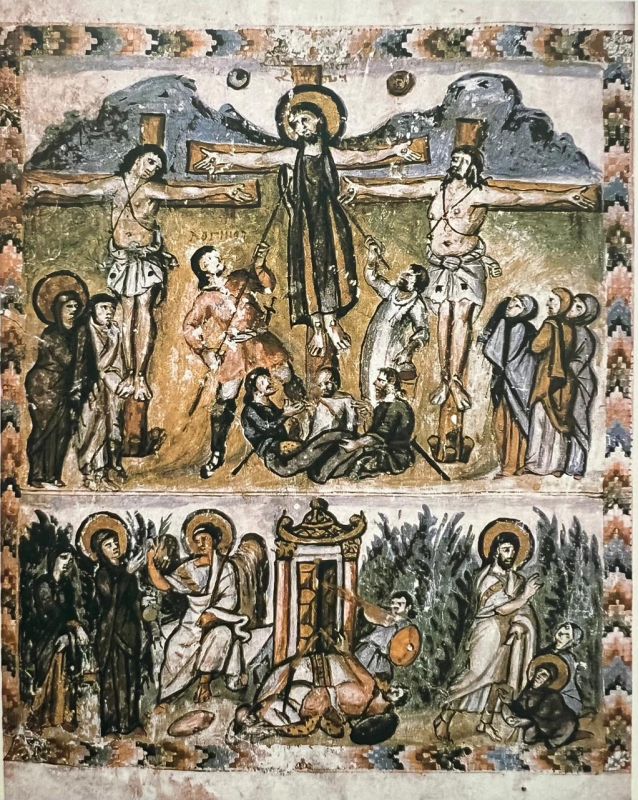

The illustration on folio 13 R° features a composition in two tiers, with the crucifixion at the top and the resurrection at the bottom. The arrangement follows a symmetrical design while incorporating free and lively elements. In the upper tier, the cross of Christ forms the center of the composition. The lower tier, on the other hand, recalls the logic of comic strips. The tomb, serving as the central point of symmetry, divides the scene into three parts: the opening of the tomb in the center; the Myrrh bearers to the left and the risen Christ revealed to the holy women on the right.

Also in two registers, the Ascension (folio 13 V°) is one of the most famous scenes in the Codex of Rabula, as it has served as a model for several modern Maronite icons and frescoes. In its upper register, Christ is depicted in a halo held by two angels, above the wings of cherubim covered in eyes, and the wheels of Ezekiel’s chariot. The wings reveal the tetra morph, or the four Evangelical symbols: The Lion of Saint Mark, the Eagle of Saint John, the Bull of Saint Luke and the Man of Saint Matthew.

In the lower register, the composition mirrors the symmetry of the upper one. Mary is at the center, framed by two angels, each addressing a group of people. In the foreground of the group on the right, we can spot the iconic features of Saint Peter, while on the left, in the foreground, we can identify Saint Paul by his baldness and beard. These details may seem trivial, but they are emblematic of Christian heritage in general, and Maronite tradition in particular. They have endured through the centuries, from the year 586 to the present day, as proof of a living legacy that can no longer — and must no longer — be overlooked.

Comments