Voting commenced across Europe for the pivotal EU elections, with a spotlight on the rise of far-right parties in countries like France and Germany potentially shaping the continent’s political landscape for the next five years.

Voting began across Europe on Sunday on the final – and biggest – day of marathon EU elections, with balloting due in 21 countries, including France and Germany, where support for surging far-right parties is being tested.

It is a pivotal time for Europe. The continent is confronted with the war in Ukraine, global trade and industrial tensions marked by US-China rivalry, a climate emergency and a West that within months may have to adapt to a new Donald Trump presidency.

The vote outcome will determine the bloc’s next parliament and indirectly the makeup of the powerful European Commission – thus helping shape European Union policies over the coming five years.

While centrist mainstream parties are projected to hold most of the incoming European Parliament’s 720 seats, polls suggest that they will be weakened by a stronger far right pushing the bloc towards ultraconservatism.

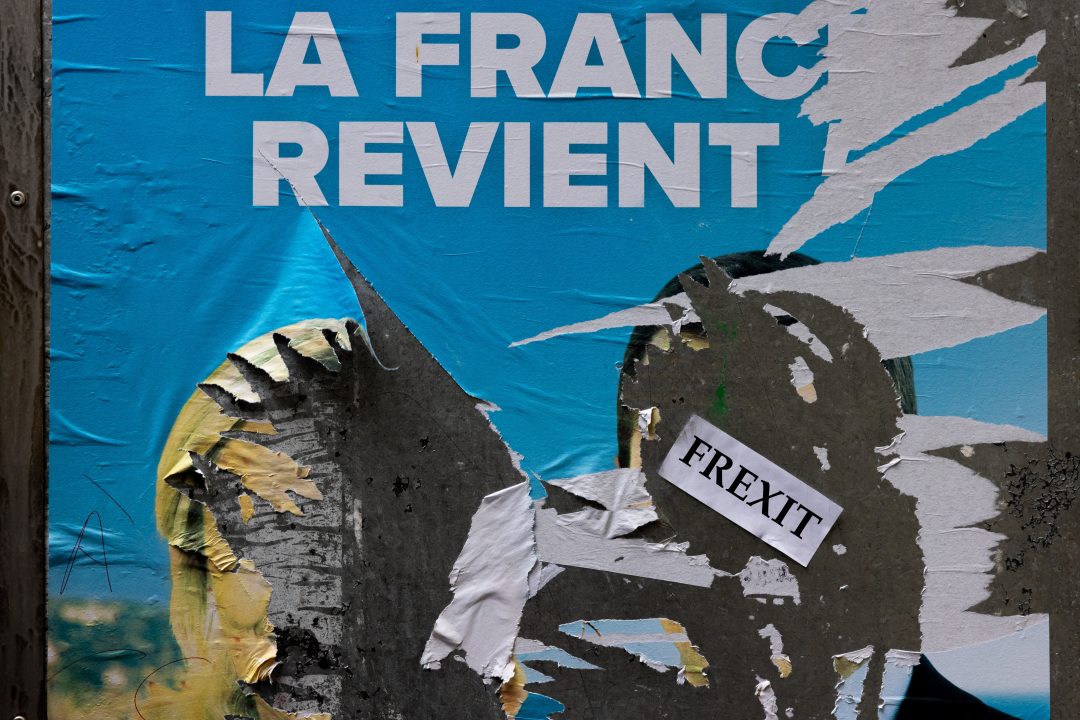

Battleground France

France will be the EU’s high-profile battleground for the competing ideologies.

With voting intentions above 30%, Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally (RN) is predicted to handily beat President Emmanuel Macron’s liberal Renaissance party, polling at 14-16%.

Le Pen is hoping to form a far-right supergroup in the European Parliament. But analysts predict that disagreements with other hard-right parties – especially over military help for Ukraine, something Le Pen is leery of – will scupper that.

In Germany, Europe’s biggest economy, the election could likewise deal a blow to Chancellor Olaf Scholz – whose center-left SPD is polling behind the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD).

Leading the polls are the center-right Christian Democrats, credited with 30% of votes – but on 14% the AfD is either neck-and-neck or ahead of all three parties in the ruling coalition: SPD, Greens and the liberal FDP.

Le Pen, who strived to shed the RN of its past reputation for anti-Semitism and xenophobia, made overtures to Italy’s far-right premier Giorgia Meloni with an eye to teaming up.

But Meloni, while fiercely opposed to undocumented asylum-seekers entering Europe, cultivated a pro-EU position and has given little heed publicly to Le Pen’s offer.

Von der Leyen’s Ambition

Unlike Le Pen, Meloni aligns with the overall EU consensus on maintaining military and financial assistance to Ukraine and encourages its ambition to one day join the bloc.

Meloni is also important to European Commission chief Ursula von der Leyen’s bid for a second mandate, which will be decided by EU leaders but also needs majority assent in the new European Parliament.

Von der Leyen, a conservative former German defense minister, opened the door to her European People’s Party (EPP) – projected to come top in the EU parliament but without a majority – working with Meloni’s far-right lawmakers.

Mainstream leftist parties fear that this could trigger a sharp rightward turn – with tougher immigration rules and a watering down of climate policies to appease angry farmers and focus on boosting industrialization.

Max Delany, Yannick Pasquet and Geza Molnar, with AFP