Listen to the article

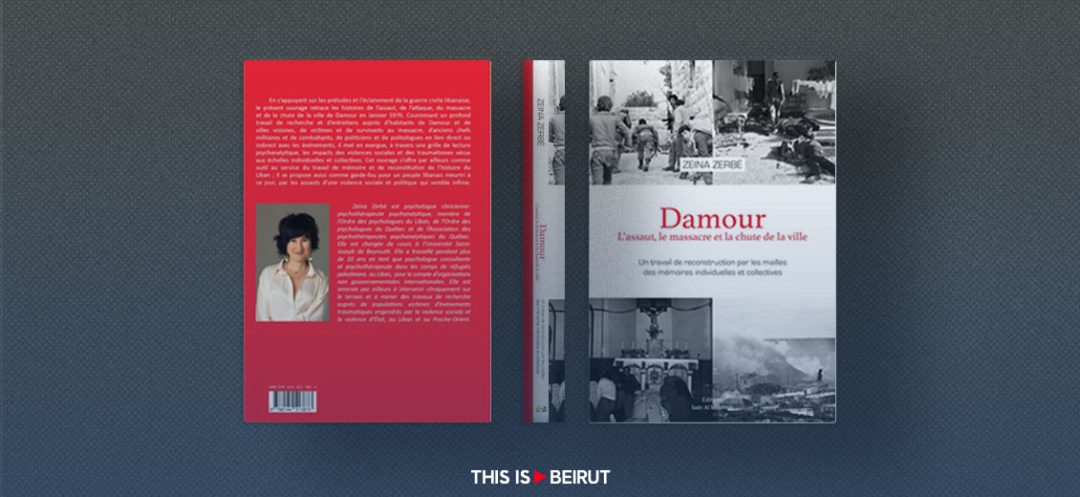

48 years later, the deadly attack launched against the town of Damour in January 1976 is still a gaping wound in the Lebanese collective subconscious. Zeina Zerbé, clinical psychologist and psychotherapeutic psychoanalyst, courageously dives into this profound trauma in her book Damour L’assaut, le massacre et la chute de la ville. A compendium of interviews with actors and witnesses from the time, this long-reaching investigation plunges readers into the heart of one of the darkest episodes of the Lebanese civil war. Beyond fact-based reconstitution of the events, Zerbé’s work is a psychoanalytic approach to deep soul-searching, an unprecedented and crucial deciphering of the reasons behind violence. An effort that helps mend wounds and promote national reconciliation.

Zeina Zerbé chronicles the inevitable rise in tensions that led to the Damour attack perpetrated by a number of Palestinian and Lebanese left-wing factions. A magnifying glass to better understand the psychological mechanisms at play, from the residents’ all-pervasive anguish vis-à-vis external threats to the trauma sustained by survivors forever haunted by the atrocities. Their blood-curdling testimonies, gathered empathetically and with analytic rigor, explode in the faces of readers. Scenes of sheer horror, devastating accounts of families torn apart by lead and flame… These individual memories help draw a portrait of this murdered town, the sacrificial victim of internal rapture, and the Syrian regime’s Machiavellian machinations.

Zerbé does not simply examine wounds; she traces responsibility to their source, questioning the motives of executioners and their ties to Damascus. Therefore, her psychological analysis of group dynamics sheds light on the impact left by orders issued from above on the fall into barbarity. A study that contests the dominant narrative and seeks the causes of violence beyond the sectarian divide. The author seems convinced: Syria’s cynical instrumentalization of sectarian hatred has played a major role in the Damour events.

But this is no mere history and psychology book; it is, first and foremost, a tool for resilience, a soothing balm delicately applied to a gaping wound. By letting the victims’ voices be heard, by exploring obscure areas relentlessly, and by linking disparate memories together, Zeina Zerbé executes masterful stitching work. She draws the outlines of an indispensable collective catharsis, the only means for the exorcism of old demons.

When asked about the therapeutic impact of her work, the author stressed that “one of the goals is for us Lebanese to step away from the unspoken and the weight of the morbid silence dictated by the current political system.” Providing a psychoanalytic study of the debilitating effect of lawlessness and the subtle fall into hatred, cruelty, and barbarity, Zerbé allowed for the history of the Damour massacre to be “recognized as having, indeed, taken place the way victims lived it.” As for the healing effect for victims and their progeny, “it is up to the residents of Damour and the people who partook in the attack to judge,” she added.

Zeina Zerbé’s subliminal message is a vibrant call for the mutual recognition of suffering as an essential component of national reconciliation. Here lies the challenge of memory: to free long-suppressed emotions, archive memories to better surpass them, and allow victims to finally mourn. For it is only by looking candidly into the past that one can build a peaceful future.

It is worth noting that, to this day, no investigation has been made by the Lebanese state over the Damour massacre. As Zerbé writes in her book, “Even though the parents and descendants of victims now know vaguely where their loved ones were buried — with no DNA testing or identification of the bodies — they still cannot, 48 years later, bring them justice, dignity, and a tomb, in order to mourn fully.” Today, in the mass grave of Damour, “the unidentified corpses of the people killed lie collectively. The despondent cries of Damour’s ghosts emanate from under the soil, whispering above the town the terrifying story of their killing.”

But should one be surprised by the glaring absence of the state? After all, the government has always been quiet about it, paying no heed to its role as guardian of justice and collective memory. It is to compensate for this total lack of work that people like Zeina Zerbé take such personal initiatives.

Can another similar event occur given the current context of turmoil in Lebanon? Is history bound to repeat itself? For Zeina Zerbé, it is crucial to understand that “the history of Damour is still happening in Lebanon repeatedly today.” Zerbé evokes the multiple aspects of this perpetual repetition: impunity, political crimes, assassinations of politicians and journalists, intimidation of activists, Hezbollah’s violation of territorial integrity, paralysis of the judicial system, the port of Beirut explosion, the deliquescence of the Lebanese State, and the undermining of laws and institutions.

By telling the unspeakable and scouring the black miasma of the human soul, Zeina Zerbé lays the foundation of a shared memory, a redeeming “ne’ermore.” Her book is a weapon against oblivion, a wake-up call so that the shortcomings of the past don’t spill over the present, a timeless message in a country plagued by its demons.

Enriched with the poignant pictures taken by a German reporter on site in 1976, the book’s blunt messaging deals a definitive blow to platitudinous sensationalism. The author stated she had enough material for a second book about the long-term repercussions of the tragedy. May she garner the energy she needs to continue this essential work and shed more light on the impact of the Damour massacre in a still-convalescing country.

Damour. L’assaut, le massacre et la chute de la ville de Zeina Zerbé, Saër el-Mashreq, 2024, 180 p.