Listen to the article

Lebanon’s Central Bank (BDL) announced in a statement on Thursday the suspension of “seigniorage,” or procedure of assessing the profit or loss made on producing a currency, and the commencement of collaborative efforts with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to review its Safeguards Assessment methodology.

When approached by This is Beirut for comment on BDL’s statement, a source within the Central Bank succinctly emphasized, “We should avoid getting lost in speculation and analysis; it’s simply another method of presenting BDL’s balance sheet, with no fundamental changes.” However, some financial and economic circles regarded it as a return to a harsh reality, acknowledging losses as well as the current inability of the Treasury to cover them entirely or partially, as outlined in Article 113 of the Code of Money and Credit (CMC).

BDL’s Statement

What exactly does BDL’s statement convey?

“The overall financial situation and the current state of the Treasury are not enough to cover the accumulated losses of Banque du Liban without implementing a comprehensive financial reform plan, inclusive of deposits in banks and the banks’ overall situation.

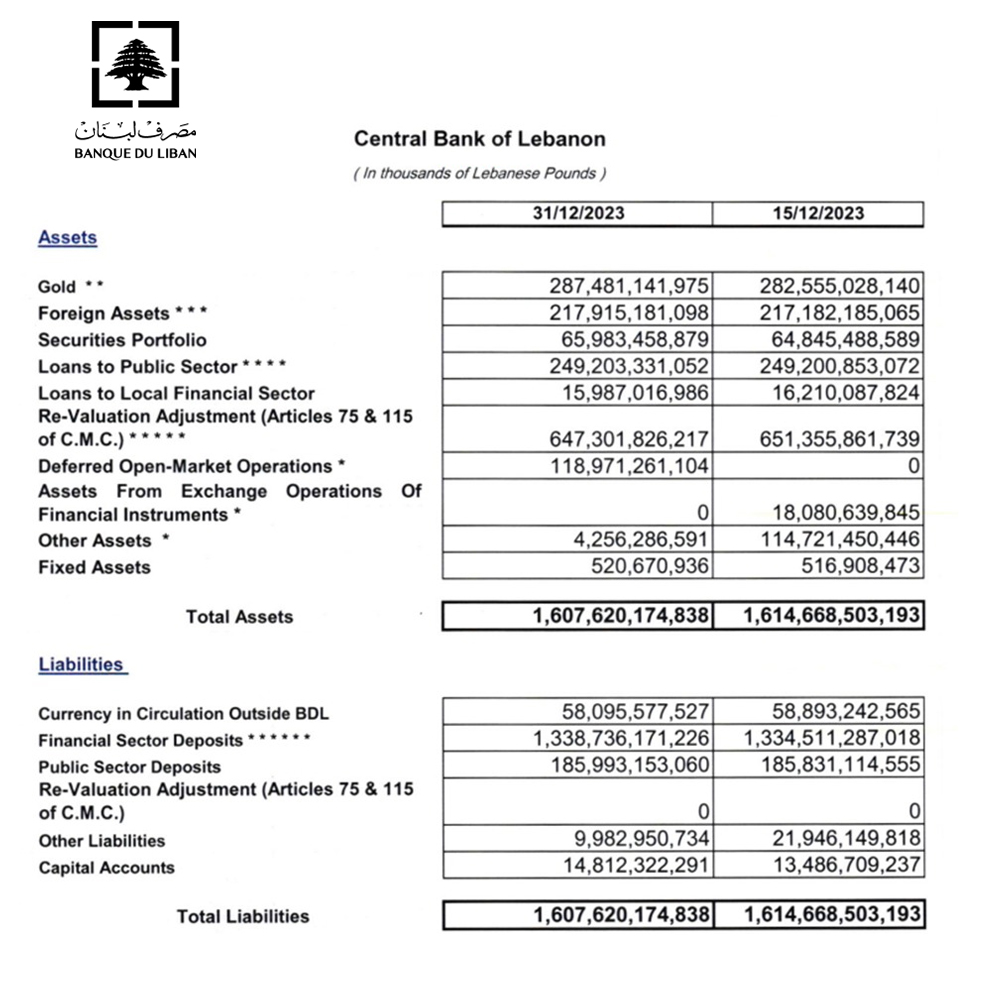

With a focus on transparency in reporting financial figures, the summary statement as of 12.31.2023 released by BDL on Thursday indicates the suspension of the seigniorage principle.

This aims to clarify all deferred charges within a new distinct item known as ‘deferred open market operations,’ aligning with international criteria and practices in understanding realized and deferred losses.”

Moreover, the BDL added, “Following the principle of compliance with international accounting standards and best practices, including Bulletin No. 68 dated 02.07.2023 published by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), which allows for negative losses and private funds of central banks to be recorded as realized and unrealized losses in the current and subsequent years, akin to recent standards adopted by numerous central banks globally.”

It also reiterated the provisions of Article 113 of the Code of Money and Credit, stipulating that if a year’s result ends in a deficit, the loss will be covered by the general reserve. In the absence or insufficiency of such reserve, the Treasury will cover the loss through parallel payment.

In conclusion, the BDL announced that it has started a collaboration with the IMF on the Safeguards Assessment project, aimed at reviewing accounting policies, reports and financial information to emphasize the adoption of optimal governance and transparency principles.

No More Concealed Losses

According to Joseph Gemayel, professor and honorary dean of the Faculty of Economics at USJ, the BDL acknowledged losses on its balance sheet by creating a new item titled deferred Open Market operations (see table above). He emphasized, “The transfer from the ‘other assets’ item – previously included in BDL balance sheets – to this newly created item demonstrates that these are deferred losses which have not materialized.”

He added that such an accounting practice aligns more with international criteria and, on another front, adheres to Article 113 of the Code of Money and Credit. In this context, the BDL explicitly clarified the state’s current inability to fully or partially cover the central bank’s deficit, indicating these as deferred losses.

Mahmoud Jebaee, economic expert, suggested that the new approach adopted by the BDL precludes any claims of “hidden losses” or “inflated balance sheets,” as referenced in the Alvarez & Marsal audit report. He highlighted, “While these losses appeared in the BDL’s prior balance sheets under the assets category, it’s evident these assets are presently unavailable.”

Seigniorage Suspension

Regarding the suspension of seigniorage operations, Joseph Gemayel interpreted it as the BDL’s intention not to offset its deficit using seigniorage.

As a reminder, this process allows central banks to generate gains by capitalizing on the difference paid by commercial banks for the cost of printing the national currency (in this case, the Lebanese pound) and its face value. This would require commercial banks to borrow money from the central bank to extend credits. “Presently, this is not the case,” noted Jassem Ajjaka, economist and professor at the Lebanese University.