Listen to the article

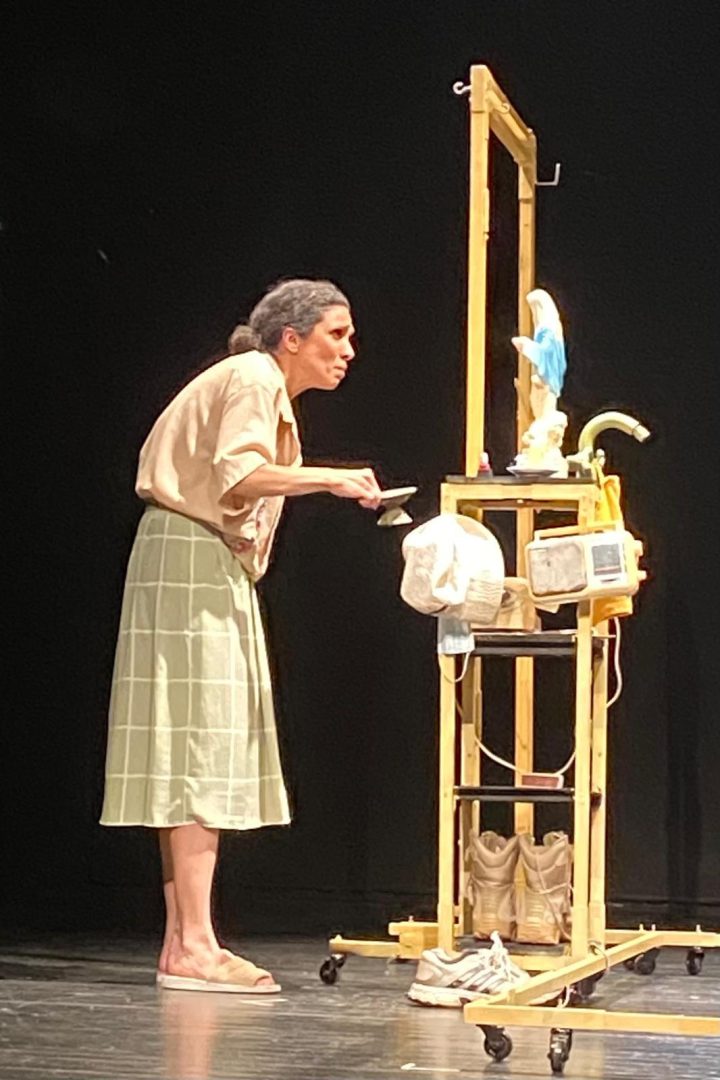

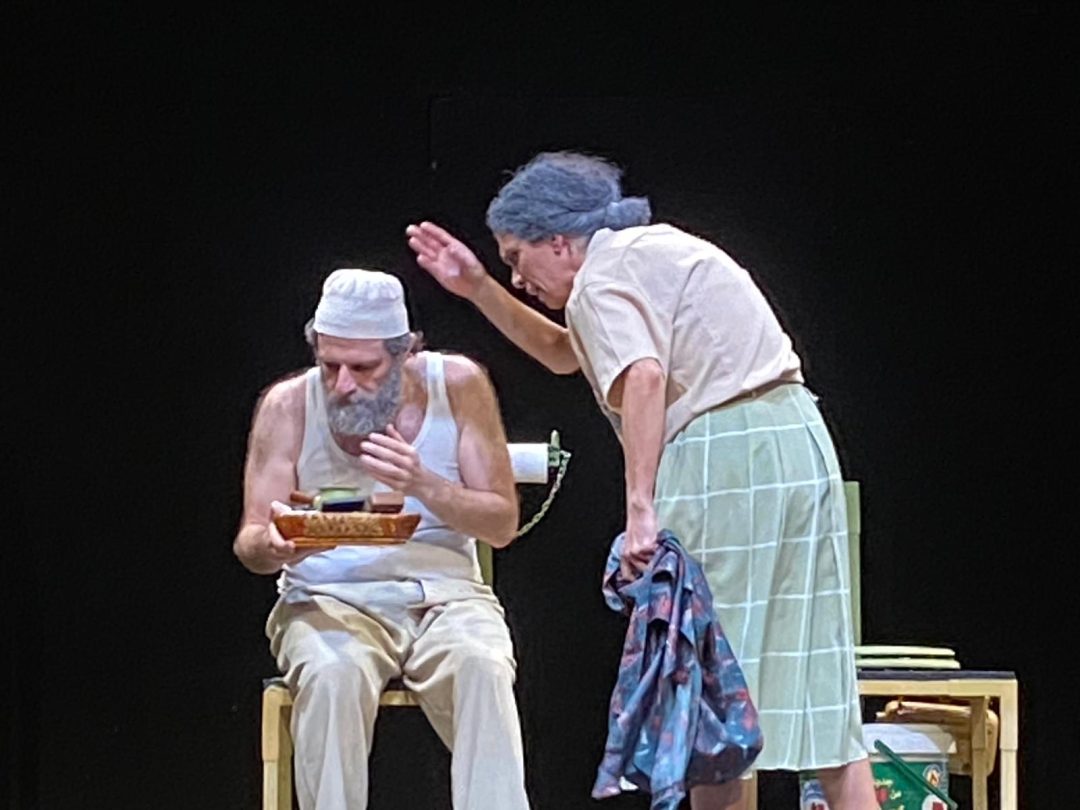

At the Monnot Theater and until July 23rd, the talented and fearless Cynthia Karam performs alongside Fouad Yammine in a play that, in barely seventy minutes and five acts, narrates an entire life under the shadow of the numerous tragedies that have befallen Lebanon. Yet, as the title suggests (Ghammed aïn fatteh aïn), everything has happened so swiftly, in just the blink of an eye: lives have been made and unmade, there have been joys and tears, loved ones have departed, but life has continued and love has survived even the worst, including death. Despite the sadness, all of this is conveyed with a sense of lightness and humor, providing Karam with an opportunity to explore a new facet of her acting talents and to virtually disappear behind her character. Unrecognizable, she embodies five periods of a woman’s life, the most remarkable of which is old age when the body becomes distorted, the timbre of the voice changes, and the gait becomes heavy. Below is a conversation with a passionate actress entirely committed to the truth.

On the night of the premiere, you invited “the real Aida” onto the stage – the woman who inspired the play. Why did you choose this particular woman, and how did your encounter with her unfurl?

This woman is the grandmother of Karim Chebli, one of the scriptwriters. Both scriptwriters, Karim Chebli and Sarah Abdo, actually drew inspiration from their own grandparents to write the play. But, in truth, the story they crafted together is the story of all Lebanese people; I can see elements that resonate with my own parents, and I believe this is the case for everyone in the audience, too. The story is that of a couple who have weathered the rollercoaster ride of the last forty or fifty years in Lebanon, all the traumas of war, all the dramatic episodes that have punctuated our lives. They go through all this with a lot of arguing, but also with profound love. The most astonishing part to me is that I started working on my character before ever meeting Aida, but when I did meet her, I felt deeply moved because I had given my character the same voice as her: down to her accent, her gait, her gestures, and even her lamentations. So meeting her was a poignant moment for me. She is a strong and dignified woman who inspired Karim and even lent us clothes that belonged to her late husband, the clothes that Fouad Yammine wears on stage. So she too was very touched last night. She felt as if she were encountering her husband again.

Was the play collectively written? Did you also contribute?

Not really. The majority of the text was penned by the two scriptwriters. But Fouad and I naturally made suggestions, changed certain lines, relocated chunks to be inserted elsewhere. The rehearsal period always allows for alterations, to better assimilate the text and enhance it.

In the first act, the elderly couple is on stage together, but in the final act, in a scene nearly identical to the first, the woman is now alone. Was this your way of demonstrating that she lives with ghosts, that our lives are haunted by the specters of those who have departed?

It was a way of illustrating that she has constructed her husband in her mind. She invented him to be able to continue living. Her husband didn’t age; he died before he could grow old. This staging underscores the woman’s solitude, the solitude of all these elderly people who live in their memories, memories that are both beautiful and filled with bitterness. Their lives are a blend of pain and laughter, because despite everything, they retain their sense of humor. But one might also say that we are all ghosts, or that we are all haunted…

You perform a remarkably demanding role. In barely seventy minutes and five scenes, you play out multiple ages spread across an entire lifetime. Do you enjoy undertaking such physical challenges in theater?

Yes, I do strive to explore something new with every role. That’s what motivates me. I enjoy immersing myself so deeply in a character that I disappear behind it. I believe that the actor should become invisible by becoming the character. And in this case, the role was very demanding, particularly in the scenes where I am an elderly woman; I have to embody this old woman in my own body, through my gaze, my gestures, my voice. Being hunched over, walking with the distinct gait of the elderly, is very strenuous. I admit that I do get physiotherapy…

Throughout the play, there’s a focus on the body through aging, but also blood, excrement, smells… Why is that? Because we wanted to get as close as possible to the truth, to depict the reality of bodies with their weaknesses, frailties, deficiencies, vulnerabilities. But at the same time, it had to remain beautiful. We shouldn’t be afraid to show what we don’t usually see, the intimacy of people, the rawness of certain things, but in a way that remains modest and respectful. At the end of the day this constitutes our common humanity.

Throughout the play, the characters are in waiting. Waiting for a son who never arrives, either due to miscarriages or because he later leaves and no longer visits his parents.

Waiting indeed characterizes so many moments, so many stages of our lives. And here, it accentuates people’s loneliness. But waiting also means retaining hope. Waiting carries energy and life. And this story of a son who never comes also allows for the exploration of the ingratitude of children, who cause their parents pain and are often oblivious to it.

War is central to the play, especially through the episode of Brahim’s death, and yet, it is scarcely present. Isn’t this paradoxical?

Not really, because the true subject of the play is the couple, not the war. Our focus is the relationship, the love story between these beings who argue, are often at odds, but genuinely love each other until the end, against all odds.

What mindset are you hoping to instill in the audience? Is your primary aim to entertain the spectators, or would you like the play to provoke reflection, a debate?

Our primary intention is to tell a story. To take the spectators on an emotional journey. We do not appeal to the intellect but to each individual heart. Our primary intention is precisely this: to share emotions. And hope that these emotions might perhaps provoke a small intimate shock; it will be up to the spectator to do something with it.