Listen to the article

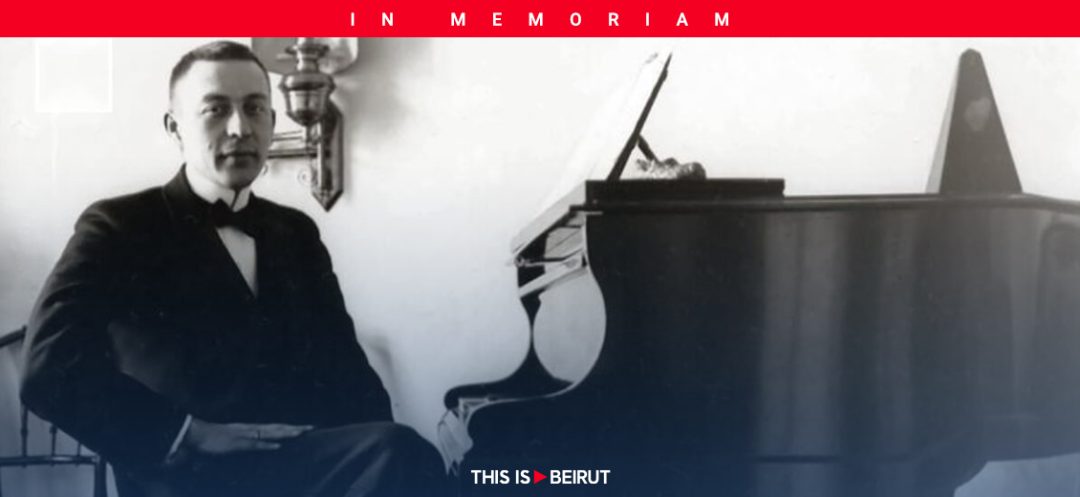

On the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Sergei Rachmaninov, last heir of Romantic era, let’s revisit, with André Lischke, this glorious period in the history of Western art music and the work of this pioneer who embraced a form of modernity later referred to as postromanticism by historians.

Fiat lux et facta est lux. The Age of Enlightenment was indeed marked by the triumph of philosophical thought and critical rationalism, arising a plethora of scattered brilliant sparks that eventually ignited a fiery blaze of knowledge. The beginning of the 18th century was the most remarkable period of transformation that the Old Continent had experienced since antiquity. The emergence of these transformations in Western tonal harmonic language at that time clearly foreshadowed a new musical era on the horizon: classicism. From the twilight of the Baroque period to the dawn of Romanticism, classical music writing underwent an evolution of its generative grammar, within which a German movement (soon to be European), known as Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress), began to germinate in the second half of the 18th century, constituting the precursor to a tumultuous and passionate innovative music: Romantic music.

Era of Nationalism

The 19th century was insatiable in its exploration of romantic spirit, where heightened sensitivity and transcendental virtuosity increasingly asserted their rights, and thus pushed the incursion to its climax. Subsequently, Western composers ardently embraced the flourishing of musical nationalism, developing personal languages that exalted the souls of their homelands, embellishing and ennobling their respective folk traditions. Frederic Chopin (1810-1849) and Stanisław Moniuszko (1819-1872) were considered symbols of Polish nationalism; Modest Mussorgsky (1839-1881) and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908), masters of the Russian school; Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884) and Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904), principal composers of Bohemia (later Czech Republic); Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) and Jean Sibelius (1865-1957), heralds of Norwegian and Finnish nationalism, and Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), founder of musical nationalism in England.

Postromantic Musical Aesthetics

An eclectic musical aesthetic, characterized by a form of modernity later entitled postromanticism by musicologists, swiftly emerged in the second half of the 19th century. While classical instrumental forms (symphony, concerto, and sonata) still prevailed during this period, notably with Johannes Brahms (1833-1897), Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893), and Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921), the symphonic poem gained increasing ground and achieved recognition with composers such as Franz Liszt (1811-1886), Antonín Dvořák, Richard Strauss (1864-1949), and Jean Sibelius, among others, before fading into Western art music history in the early 20th century. This spirit of freedom also extended to other musical genres. In the realm of opera, the Italian bel canto tradition of Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868), Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835), and Gaetano Donizetti (1797-1848) was entering a phase of decline.

During this phase of constant experimentation and refinement of musical and dramatic means, the dominant influence of Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) was strongly felt through his operas imbued with intense emotional power. Similarly, Richard Wagner (1813-1883) stood out with his innovative vision of Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art,” which was also increasingly influential. At the turn of the 19th century, a new breath seized Italian opera, shaking the established supremacy of Giuseppe Verdi and Richard Wagner. Thus, the emergence of verismo in Italian opera, influenced by the French naturalist literary movement, and Georges Bizet’s (1838-1875) opera Carmen paved the way to the end of the romantic era by introducing raw realism coupled with an authentic representation of the human condition, foreshadowing the postromantic movement that would follow.

This neoromantic breath extended into the 20th century, carried by the dynamic compositions of Richard Strauss (1864-1949), the enchanting melodies of Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), the impressionistic colors of Claude Debussy (1862-1918) and Maurice Ravel (1875-1937), the symphonic grandeur of Anton Bruckner (1824-1896) and Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), and the tormented soul of Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943). Acclaimed as one of the last true messengers of this musical era, he carried the final flames of romanticism in his work with unmatched lyrical grace, remaining faithful to tonality and to the expression of emotions, and fiercely resisting the experiments of the musical avant-garde, which he openly despised and which returned the sentiment. The same was true for Sibelius, who was also “out of sync” with his time, arousing the aversion of serialists but nonetheless establishing a magnificent presence in the repertoire.

Transmission Belt

“Rachmaninov quickly found his musical style and largely stuck to it, although he was not completely indifferent to certain harmonic achievements. In that sense, he was considered rather advanced, compared to Rimsky-Korsakov’s generation of students like Liadov, Glazunov, and Arensky, who were more like followers of their predecessors,” explains the eminent French musicologist André Lischke, specialist in Russian music, in an interview with This is Beirut. Rachmaninov’s music is characterized by expressive melodies, sophisticated harmonies, dynamic contrasts, pianistic virtuosity, emotional atmosphere, and expressive use of orchestra, giving it a recognizable personal touch that contributed to his fame and success. According to the French musicologist, he possesses that emotional “transmission belt” that is the hallmark of true romantic creators: “I believe that Rachmaninov continues to be rediscovered beyond a handful of overplayed works.”

Russian Soul

Tchaikovsky reigned as the absolute master of Russian musical universe during that blessed era. The melodic splendor and heightened emotional expressiveness of Tchaikovsky visibly ignited the soul of the postromantic composer, captivated by that predominant magisterial aura, prompting him to shape his own musical style while perpetuating the Russian romantic heritage. “Tchaikovsky actively supported his beginnings, and as a sign of gratitude, Rachmaninov dedicated his grand Trio élégiaque No. 2 in D minor to his memory,” explains André Lischke. However, he points out that the combined influence of Robert Schumann (1810-1856), Frederic Chopin, Franz Liszt, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, as well as Russian nationalist composers, particularly Alexander Borodin (1833-1887), is evident in the work of Sergei Rachmaninov. “As for his Russian character, it is less pronounced than in other Russians if we judge solely by the use of folk melodies, but I find it deeply Russian due to the emotional scope of his Melos, and especially due to the omnipresence of bell sounds in his music, particularly in his piano compositions but not exclusively,” he adds, mentioning certain passages from the Vespers that resonate with harmonies reproducing the sonorous halo of Russian bells, which had marked him since his childhood in Novgorod.

In the West, Rachmaninov actively supported his compatriot Nikolai Medtner (1880-1951), who certainly suffered somewhat from his proximity; this is an example of the “transmission belt” problem, with Medtner’s belt not functioning as effectively as Rachmaninov’s. His encounters with Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) in the United States can be considered more of an anecdote. There was also Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936), who requested and obtained permission to orchestrate several of Rachmaninov’s Études-Tableaux, a cycle of 17 solo piano pieces composed by Sergei Rachmaninov and grouped into two opuses (Op. 33 and Op. 39). “Apart from that, I believe he had very little contact with other composers, as he was too preoccupied with his concert activities,” André Lischke specifies. However, he regularly collaborated with conductors such as Arthur Nikisch (1855-1922), Fritz Reiner (1888-1963), and Leopold Stokowski (1882-1977), and violinists like Fritz Kreisler and Jascha Heifetz (1901-1987), as well as renowned opera singers, including Feodor Chaliapin (1873-1938).

With his unmatched pianistic virtuosity and emotionally rich musical language, Sergei Rachmaninov, who would have celebrated his 150th anniversary this year, clearly established himself as one of the greatest composers of his time. His musical legacy, characterized by lyrical, expressive, and expansive melodies, and harmonies rich in chromaticism, evocative progressions, and dense polyphony, continues to fascinate musicologists, testifying to his undisputed place among the iconic figures in the history of music. His influence endures, inspiring new generations to explore the depths of musical expression and seek eternal beauty beyond the boundaries of time and the current decline experienced by Western art music.