- Home

- Highlights

- Turkey and Qatar: Key Supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood?

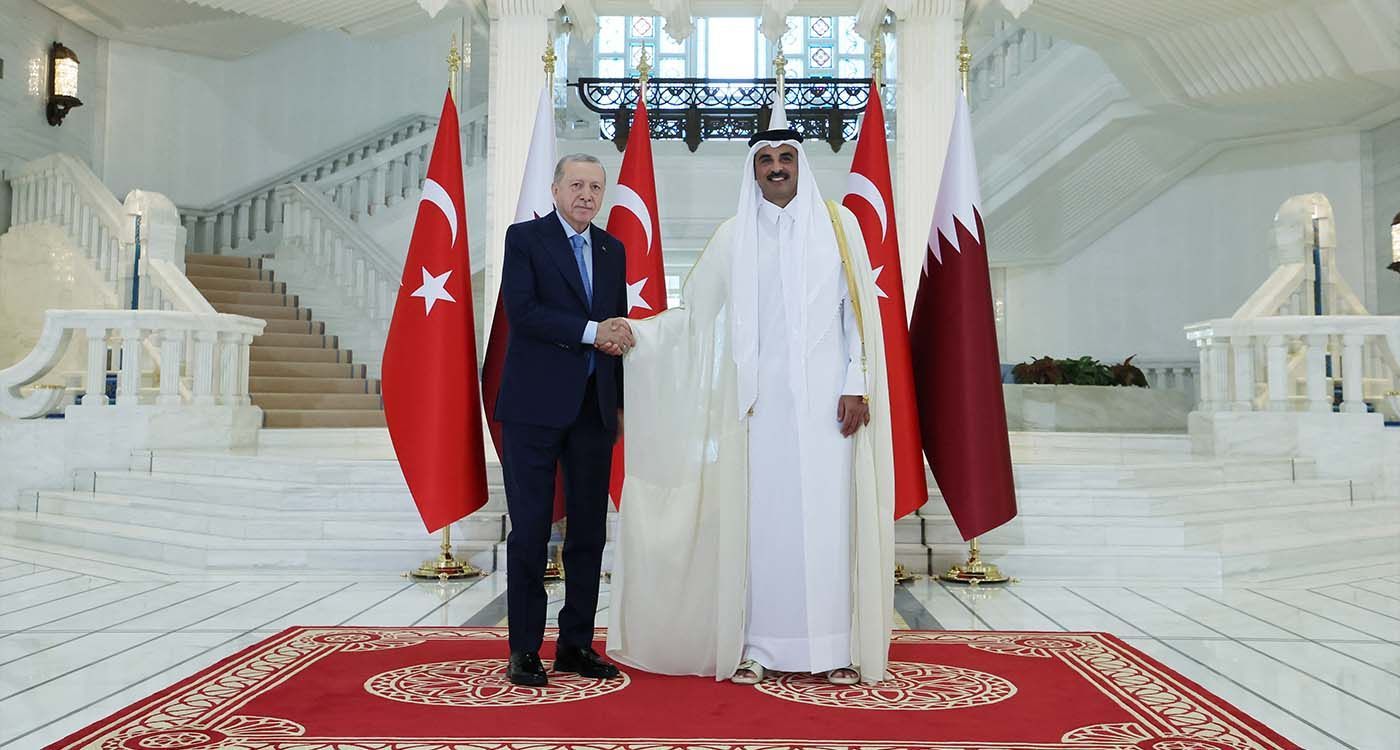

©Turkish Presidency Press Office / AFP

The outbreak of the Arab Spring in many Middle Eastern countries gave the Muslim Brotherhood a major opportunity to assert itself within newly emerging governments, most notably in Egypt and Tunisia.

Behind this rise, Qatar and Turkey were accused by critics of actively supporting and promoting the movement through financial backing, diplomatic hospitality, and media visibility.

The Brotherhood and Qatar’s Gamble

First expelled from Egypt under Nasser, and later from Saudi Arabia following Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, several members of the Muslim Brotherhood found refuge in Qatar. There, Emir Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, newly ascended to power, viewed the Brotherhood as a strategic asset, an opportunity to expand Qatar’s influence regionally and internationally. His aim was to support opponents of authoritarian regimes across the region so that, once in power, they could help Qatar enhance Qatar’s reach and prestige.

In 1961, the Egyptian preacher Youssef al-Qaradawi was sent by Al-Azhar University to Qatar to serve as dean of the Secondary Institute of Religious Studies. A lifelong member of the Muslim Brotherhood—a commitment that led to several years of imprisonment—he is widely regarded as the spiritual guide of the Brotherhood. In 1973, he was tasked with creating the Department of Islamic Studies at Qatar University, and in 1977, he went on to found Qatar’s first university dedicated to Sharia and Islamic studies. Author of more than 120 books, al-Qaradawi hosted the highly popular program Al-Sharia wal-Hayat on Al Jazeera from 1996 to 2013, giving the Muslim Brotherhood a major platform to broadcast their ideas globally.

From the 2000s onward, Qatar also provided financial support to movements and organizations aligned with the Muslim Brotherhood in the Middle East and Europe, notably through the NGO Qatar Charity.

When the Arab Spring broke out, Al Jazeera became a key platform for covering the revolutions that brought Brotherhood-linked movements to power in Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco. However, these upheavals were met with hostility by regional powers such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, which later designated the Brotherhood a terrorist organization.

In contrast, Qatar supported Mohammed Morsi’s government in Egypt by donating $5 billion and committing to invest $18 billion over five years to bolster the Egyptian economy, in addition to providing free gas supplies. It also backed the Tunisia’s Ennahda movement, hosting joint military exercises with the Tunisian armed forces from 2012 and supplying them with military equipment.

During the 2013 coup against Mohammed Morsi, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia supported General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. According to researcher Stéphane Lacroix, Qatar’s isolation by several Gulf countries between 2017 and 2021 was largely the consequence of its support for the Muslim Brotherhood.

Amid this isolation, Qatar found a key ally in Turkey, which has also been accused of backing the Muslim Brotherhood. “Many of the frequently asked questions about Qatar, Turkey, and the Muslim Brotherhood are actually shaped by the Emirati narrative,” says Andreas Krieg, lecturer at the School of Security Studies at King’s College London. “These portrayals depict the Brotherhood as a centralized and homogeneous organization with a unified ideology, whereas no such entity exists.”

According to the researcher, the group known as the Muslim Brotherhood is actually a diverse and often fragmented constellation of movements, parties, charitable organizations, and individuals: some reformist and committed to political pluralism, others more conservative, and even revolutionary.

“Qatar’s involvement with figures from this spectrum has been less about sponsoring a monolithic movement and more about positioning itself as a host and mediator for a wide range of dissidents: Arab nationalists, liberals, leftists, and Islamists. Brotherhood-affiliated personalities represented only a part of this broader landscape,” he explains to This is Beirut.

Regarding Turkey under Erdogan’s AKP, he notes that “the ties established with groups inspired by the Brotherhood after the Arab Spring reflected both ideological affinity and a geopolitical strategy to counterbalance the UAE–Egypt–Saudi axis.”

Erdogan’s Turkey as a Blueprint

The Justice and Development Party (AKP), in power in Turkey, is ideologically close to the Muslim Brotherhood, though it remains formally independent. This ideological affinity reflects convergence of interests: for the Muslim Brotherhood, Erdogan’s Turkey represents a successful model of political Islam, electorally viable and publicly supported; for Turkey, the Brotherhood provides a means to extend its influence in the Middle East.

During the Arab Spring, Erdogan supported various Brotherhood-affiliated movements, notably Tunisia’s Ennahda movement and Egypt’s government under Mohammed Morsi.

In a video released in 2014, the spiritual leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, Youssef al-Qaradawi, stated that “Erdogan is in a way the current caliph of Muslims, and Istanbul is undoubtedly the capital of the Islamic caliphate,” signaling the Brotherhood’s support for Turkey’s leadership.

Following the overthrow of Mohammed Morsi in Egypt, many members of the Muslim Brotherhood sought refuge in Turkey. Meetings of Brotherhood-linked organizations, such as the Council of European Muslims (CEM) and the European Council for Fatwa and Research (ECFR), which had previously convened mainly in Europe, increasingly shifted to Istanbul. Turkey also hosts Muslim Brotherhood–aligned media outlets broadcasting from the country, such as El-Sharq, Mekameleen, and Watan.

Like Qatar, Turkey has supported multiple organizations in Europe linked to the Muslim Brotherhood. “In Europe, Qatari and Turkish connections with actors influenced by the Muslim Brotherhood have largely operated in parallel rather than in coordination,” says Andreas Krieg, who notes that “Doha’s contribution is mainly through media and funding, while Ankara’s comes through hosting, political space, and audiovisual platforms.”

A Partial Split

Starting in the 2020s, Turkey and Qatar began distancing themselves from the Muslim Brotherhood. As Andreas Krieg explains, “Both states adjusted their relations without fully ending them. Turkey reduced or closed certain Brotherhood-linked media outlets in Istanbul as part of its reconciliation with Cairo and the Gulf capitals. Qatar, meanwhile, following the Gulf Cooperation Council’s reconciliation in Al-Ula in 2021, reduced the public visibility of some exiles while keeping its doors open to a wide range of opposition figures.”

This recalibration effort pursued by both Turkey and Qatar dealt a blow to the Muslim Brotherhood. In 2022, Ankara shut down the Mekameleen channel and stripped Egyptian Mahmoud Hussein, who led a branch of the Brotherhood in Turkey, of his Turkish citizenship. The country also curtailed the movement’s presence within its borders. Meanwhile, Qatar asked several Muslim Brotherhood leaders to leave the country to ease regional tensions and reduce the movement’s public visibility footprint.

Yet this distancing is not total. Turkey, for instance, continues to host Brotherhood cadres, while Qatar still supports certain organizations, but in a more discreet and measured way. The aim for both states is to preserve their ties and influence in the region while maintaining support for their Brotherhood allies.

Read more

Comments