On the eve of winter vaccination campaigns, Didier Raoult reignites controversy by claiming that a large South Korean cohort “confirms” an increase in cancers among vaccinated people. Yet the study speaks of associations, not causation. This is Beirut has gathered and cross-checked analyses from Lebanese specialists, and sets the record straight, testing the claim against both clinical practice and the available literature. Between scientific prestige, COVID-era media frenzy and a battle over evidence, what does the medical literature actually say?

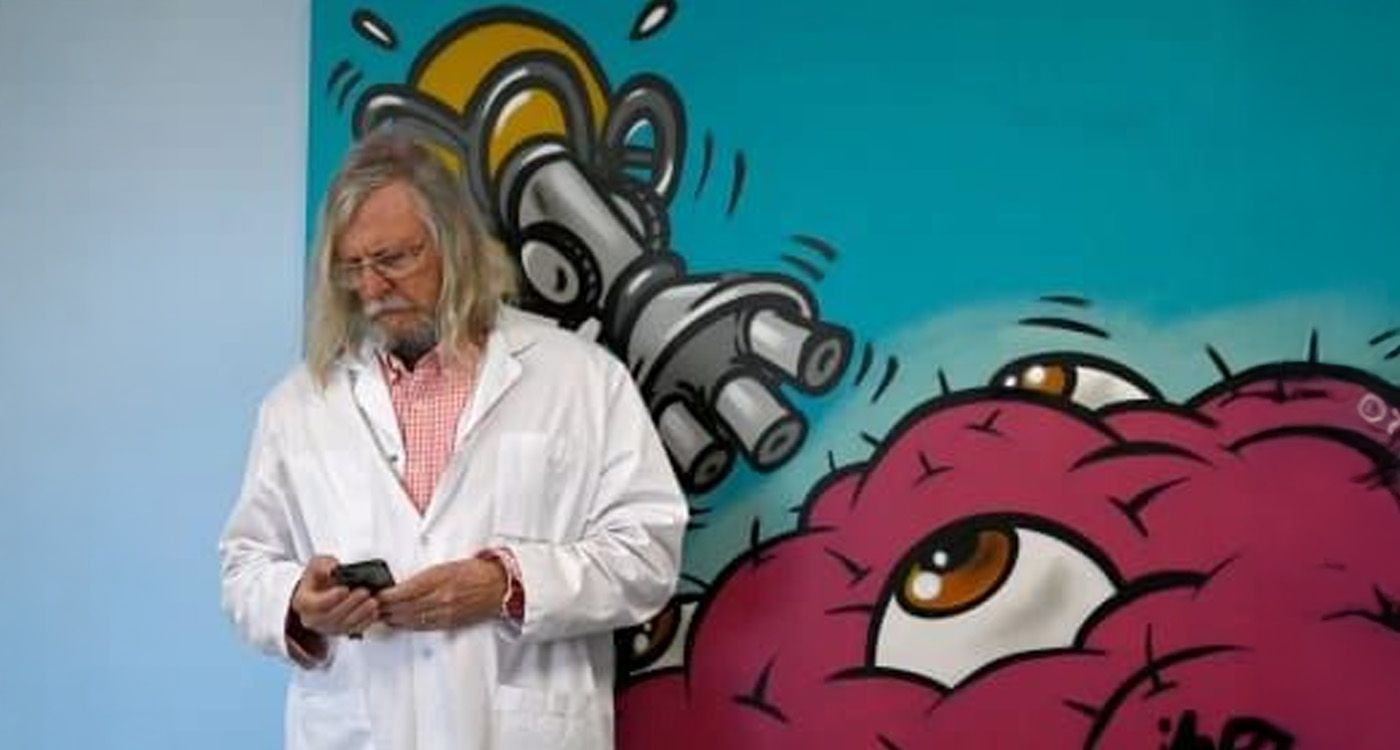

An internationally reputed microbiologist before 2020, Didier Raoult moved to the eye of the media storm with his promotion of hydroxychloroquine.

Raoult, from Mandarin to Divisive ‘Star’

Since then, investigations, methodological critiques and disciplinary proceedings have piled up: in May 2023, his “off-protocol” regimens and a massive Marseille study were publicly challenged; in October 2024, the French Medical Council imposed a two-year practice ban (effective February 1, 2025) for the imprudent promotion of hydroxychloroquine and statements undermining public-health guidance. Judicial inquiries remain open concerning “unauthorized” trials at the IHU-MI.

On the therapeutic evidence front, major randomized trials (RECOVERY, WHO-Solidarity) showed no clinical benefit for hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized COVID patients, and the FDA withdrew its Emergency Use Authorization as early as June 2020.

What the Korean Cohort Actually Shows

Biomarker Research published a South Korean cohort study (national health insurance data; 8.4 million people; 2021–2023). Over one year post-vaccination, the authors observed statistical associations with six cancers (thyroid, stomach, colorectal, lung, breast, prostate), with variations by vaccine regimen (mRNA, “cDNA,” heterologous). The authors explicitly state that they do not establish a causal relationship and call for further research.

In the hours that followed, several media outlets – wrongly – headlined that the researchers had “proven” a link; newsrooms later corrected their articles, noting that the study does not demonstrate that vaccines cause cancer.

Lebanese Perspectives: Explaining, Confirming, Nuancing

In Beirut, clinicians ground the debate in day-to-day care.

Jacques Choucair (assistant professor at Hôtel-Dieu de France, HDF) begins, “I have known and worked with Didier Raoult. He was a respected physician. But his positions during the deadliest phase of COVID, followed by increasingly controversial decisions, eroded his aura.” On substance, he confirms, “I see no correlation between vaccination and cancer. Without proof, we can’t rely on mere observations. In fact, once vaccination started, COVID mortality declined.”

Marwan Ghosn (oncologist and professor of medicine at HDF) adds a crucial piece of context: “During COVID – especially in the first two waves – the percentage of diagnosed cancers fell, which was logical: screening campaigns collapsed and patients avoided hospitals and clinics for fear of infection. Later, when screening resumed, the rates unfortunately rose again.” He further notes, “To date, in our practice, we have not observed any increase in cancer incidence attributable to the vaccination campaigns.”

A Lebanese internist, supportive of the IHU’s “all-terrain” approach, tempers the crisis-time therapeutic stance: “In the midst of an epidemic, you don’t always have the luxury of waiting for long trials; you mobilize whatever tools you have.” Still, he concedes, this does not justify turning a statistical signal into a causal verdict.

What to Understand – at a Glance

An observational cohort can detect coincidences; it cannot settle causation. Even with careful matching, it remains exposed to two classic pitfalls:

– Detection bias: in a country with very active screening (and a past history of thyroid over-diagnosis), patients who seek care more often are diagnosed more often – without a “real” rise in disease.

– Confounding factors: health behaviors, socioeconomic status, exposures, prior infections, care pathways… are never fully captured.

To move from association to cause, we need more granular individual data, study designs that limit these biases (prospective cohorts, target-trial emulation, randomization when ethically acceptable) and solid biological plausibility (a reproducible mechanism, dose–response gradients). As it stands, the Korean cohort points to a lead worth exploring, not a verdict.

So: hero or zero? Time will tell. For now, the evidence demands that we don’t mistake signal for judgment. The ethics of scientific communication require stating exactly what the authors say: an association, hypotheses and much work are still needed to decide. Between clinical intuition and trial rigor, medicine is built on facts – not shortcuts.

Comments