Composed in 1933 by Rezső Seress, “Gloomy Sunday” carries a dark reputation: the song is said to have triggered a wave of suicides. A look back at the sinister legend of a piece that became a symbol of universal despair.

It is rare for a song to inspire as much fascination, dread and myth as “Gloomy Sunday.” Written in the depths of the Great Depression by Hungarian musician Rezső Seress, this melancholy waltz has carried with it for nearly a century a trail of persistent rumors: branded the “suicide song,” it was allegedly banned from airwaves and accused of driving dozens to take their own lives. At the crossroads of social reality, historical misunderstanding and urban legend, what does this story truly reveal?

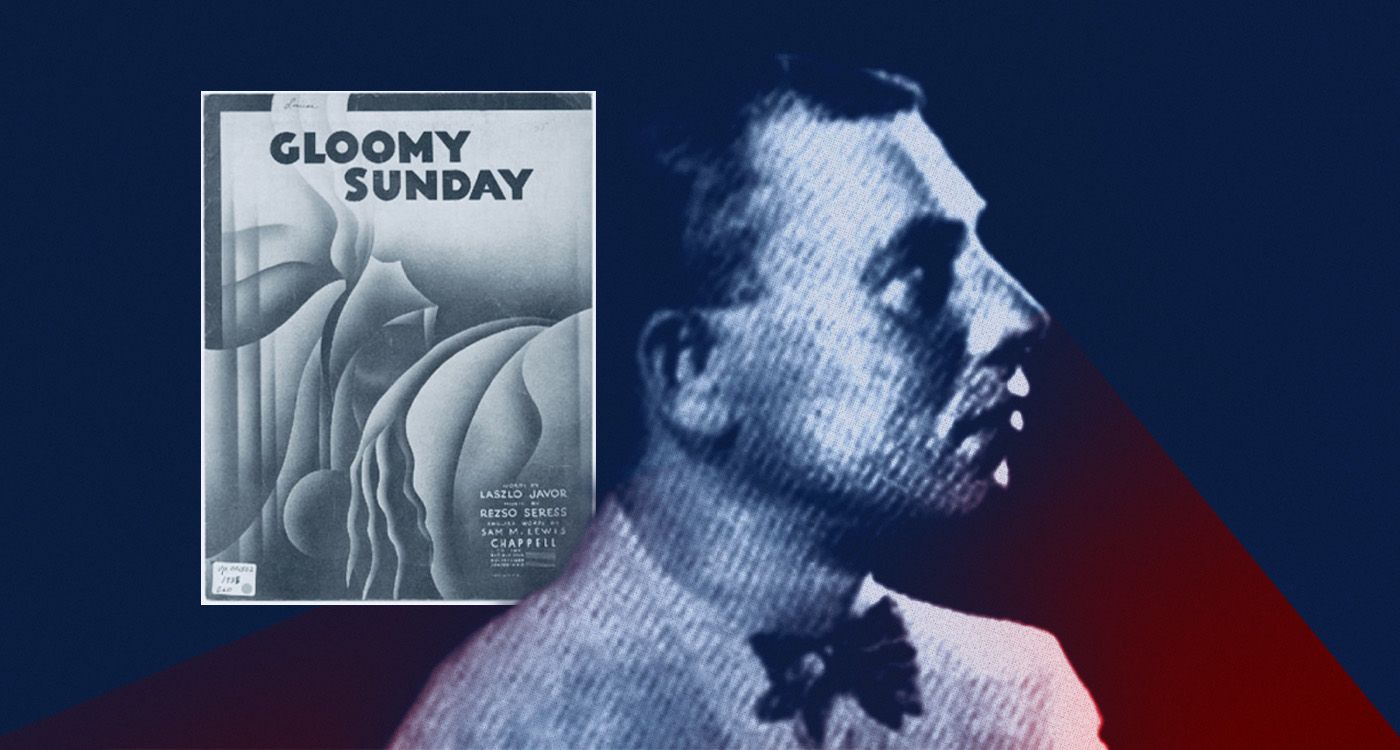

Rezső Seress was hardly destined for posterity. A self-taught pianist, he composed while in Paris in 1932 a simple yet haunting melody, said to have been inspired both by his own romantic despair and by the grim atmosphere of an era marked by mass unemployment and poverty. The first version, titled “Vége a Világnak” (“The End of the World”), read like an existential lament. But it was in Hungary that the song took its definitive form, when poet László Jávor penned new lyrics focusing on the grief of a man mourning a lost love. Thus, was born “Szomorú Vasárnap-Gloomy Sunday.”

The piece quickly found its way into Budapest cabarets. Its overwhelming sadness and heartbreaking lines, “My heart and soul are crying, it’s a gloomy Sunday,” resonated with an audience already devastated by the crisis. In 1930s Hungary, suicide rates were among the highest in the world, driven by poverty, insecurity and isolation. Against this backdrop, stories began to circulate: newspapers reported suicides where the sheet music of “Gloomy Sunday” was found near the deceased, or farewell notes that mentioned it. Soon, the myth took on a life of its own.

Internationally, the tale grew darker. In Budapest, a young woman was said to have thrown herself into the Danube with the score in hand; elsewhere, a restaurant owner allegedly ended his life after hearing it on the radio. None of these accounts were ever verified, yet the legend spread. By the time the song crossed the Atlantic, it already bore the nickname “the Hungarian Suicide Song.” In 1941, Billie Holiday gave it new life: her raw, aching interpretation turned the piece into a cult classic.

The real turning point came in London. Disturbed by the rumors, the BBC banned the broadcast of the sung version for decades, allowing only the instrumental version. This fact, unlike many of the stories, is well-documented, and it reinforced the song’s sinister reputation. In Hungary, some institutions are also said to have banned it temporarily, though no official proof remains. “Gloomy Sunday” thus became taboo, feared and admired in equal measure. It was, in brief, a “cursed” song.

Researchers who have studied the phenomenon agree on one point: no suicide wave can be scientifically attributed to the song. Deaths reported in the press were largely products of journalistic exaggeration or urban folklore. What truly explains Hungary’s epidemic of suicides were the social conditions of the time: war, poverty, loneliness. “Gloomy Sunday” was more a mirror of collective despair than its cause, a lament rather than a trigger.

The tragic fate of Rezső Seress only deepened the curse’s aura. A survivor of Nazi persecution, but consumed by depression, he took his own life in 1968, almost as if to seal the fatalistic legend tied to his creation. Yet, behind the dark myth lies a more complex truth: “Gloomy Sunday” stands above all as proof of music’s ability to crystallize the anxieties of an era and to speak directly to all those left on the margins of life.

Comments