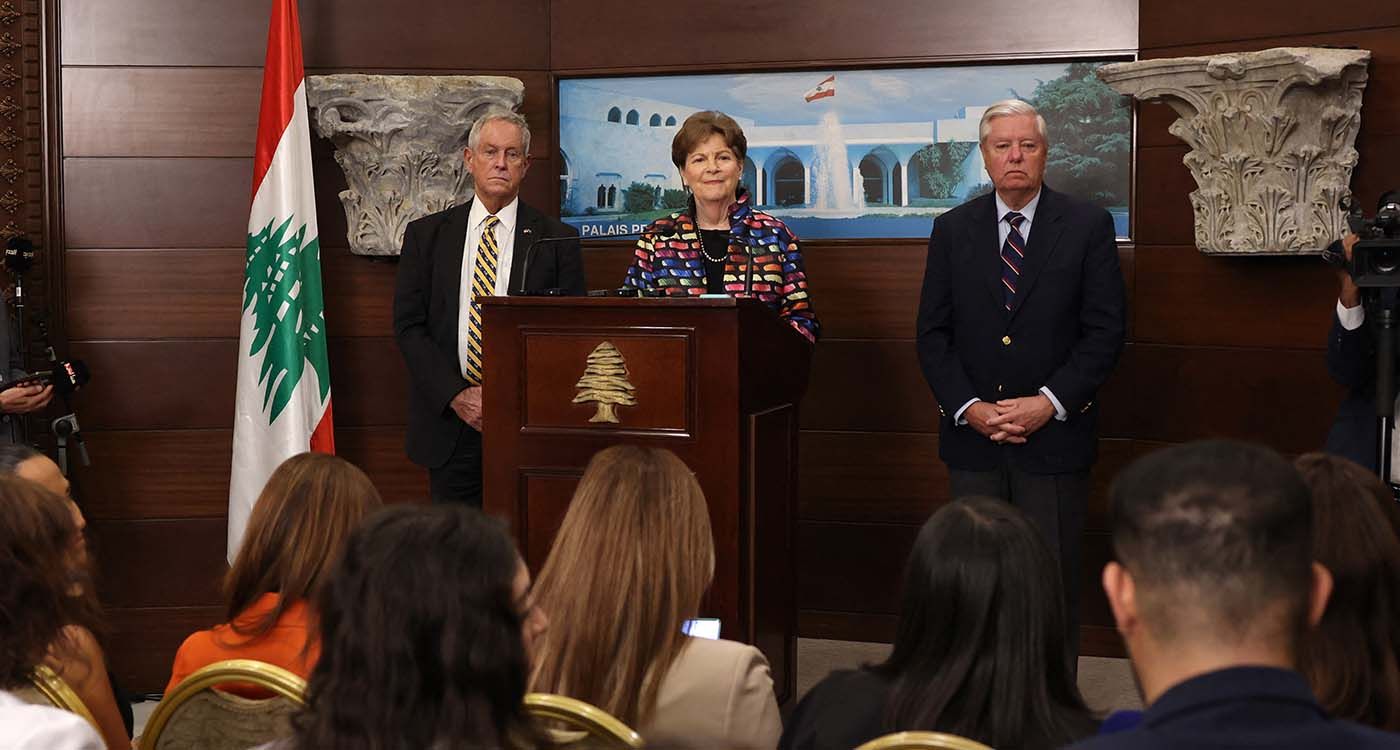

When Tom Barrack, Morgan Ortagus and Senator Lindsey Graham touched down in Beirut, it was clear that the United States was no longer willing to watch Lebanon’s crisis unfold from the sidelines. Their visit was not ceremonial. It was an intervention, part carrot, part stick, designed to push Lebanon into one of the most consequential decisions in its modern history: whether it can disarm Hezbollah without tearing itself apart.

The delegation had just left Jerusalem, where they met with Israeli leaders, including Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Defense Minister Israel Katz.

Their agenda in Beirut was sharp and urgent: Hezbollah’s weapons; urging Lebanese leaders to implement a plan that restores the state’s monopoly on arms; ceasefire guarantees; securing Lebanese buy-in for an arrangement that halts Israeli strikes and promises withdrawal from occupied Lebanese land; regional stability; aligning Beirut and Damascus with Washington’s wider effort to stop the Israel–Iran shadow war from exploding across the Levant.

At Baabda Palace and the Grand Serail, President Joseph Aoun and Prime Minister Nawaf Salam entertained the plan. However, Speaker Nabih Berri drew a red line: no Lebanese concession without ironclad Israeli guarantees. The Lebanese Army, caught in the middle, was ordered to produce a framework by the end of August, careful to avoid igniting sectarian tensions, and the deadline ends today.

Tom Barrack cast the project as a “step-by-step” choreography: Lebanon presents a plan that persuades Hezbollah fighters to transition into civilian life; Israel reduces “non-essential” strikes and begins a phased pullback from its border outposts.

This approach avoids demanding the impossible overnight. But critics note the imbalance: Lebanon must dismantle its non-state actor, while Israel’s obligations remain vague. Without clear reciprocity, the plan could falter.

Morgan Ortagus, serving as deputy special envoy, sharpened the message. Lebanon, she said, faces a stark choice: comply with the US framework or risk renewed Israeli escalation. Her blunt language may have clarified Washington’s expectations, but it also risked sounding like an ultimatum in a country where compromise, not absolutes, is the currency of politics.

Senator Lindsey Graham added congressional weight. He dangled incentives: deeper US–Lebanese military cooperation, a potential defense agreement and international aid, all conditioned on tangible steps toward disarmament. For Lebanese leaders navigating economic collapse and donor fatigue, the promise of new security and financial lifelines was difficult to ignore.

Lebanon’s dilemma is not just political, it is economic. Hezbollah operates as both a militia and a welfare network, paying salaries, running clinics and managing trade. Barrack’s answer was a Gulf-funded development zone in southern Lebanon, bankrolled by Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

The concept is to convert Hezbollah’s payroll into regular jobs, absorb fighters into a revitalized economy and create a peace dividend. But in Lebanon’s patronage-ridden system, skeptics ask: Will the money really reach disarmed fighters’ families, or be swallowed by contractors and politicians?

In parallel, Barrack and Ortagus pressed Jerusalem to temper its own behavior. Their talks in Paris with Strategic Affairs Minister Ron Dermer outlined a tentative quid pro quo: if Lebanon advances on disarmament, Israel must scale down strikes and test withdrawal from one or more occupied positions. This reciprocity, quiet and fragile, is the linchpin of the entire effort.

President Aoun and Prime Minister Salam know their survival depends on framing the initiative as a sovereignty project, not a sectarian confrontation. Their line is clear: no internal war, no coercion. The state must reclaim the gun gradually, while Israel reduces its footprint.

That balancing act is perilous. Push too hard, and Hezbollah’s Shia base feels besieged. Move too slowly, and Israel resumes its air campaigns.

Yet, even as Washington tried to choreograph diplomacy, Barrack undercut his mission. During a press conference, he scolded Lebanese journalists as “animalistic” and demanded they “act civilized.” The backlash was immediate, accusations of colonial arrogance, a wave of protests and the cancellation of a planned southern tour. In Lebanon, where dignity is as political as sovereignty, the misstep reinforced suspicions that Washington’s agenda humiliates more than it helps. Later on, Barrack’s team stated and clarified that the Ambassador meant “Anomalistic.”

The looming question is whether Israel will launch a major operation next month.

Why it won’t: Israel has hinted at a gradual pullback if Hezbollah disarms, the Lebanese cabinet approved a disarmament plan by year’s end and Washington is pouring diplomatic capital into de-escalation.

Why it might: Hezbollah remains defiant, Lebanon’s political divides could stall the plan and a single border incident could trigger retaliation. Add Syria’s instability, and the risk of miscalculation remains high.

The most likely scenario: Israel holds off on a full-scale operation in September, but continues calibrated strikes. The US mediation buys time, not peace.

The Barrack-Ortagus-Graham mission was the boldest American diplomatic thrust in Lebanon in years. It laid out a simple trade: guns for jobs, disarmament for withdrawal, sovereignty for aid. But Lebanon is not a place where simple trades hold.

Disarming Hezbollah is not just about weapons, it’s about identity, economics and survival. What is unfolding today in Beirut is not just another round of diplomacy, it is the start of a new chapter for Lebanon and the wider region. The delicate balance of pressure, incentives and international guarantees is gradually reshaping the political map. For decades, Hezbollah’s weapons defined the limits of the Lebanese state. Now, those limits are being tested, and for the first time, there is a realistic framework to restore sovereignty without plunging into civil war. Change in Lebanon will not come overnight, and the region’s rivalries will not vanish with a single agreement. But the direction is clear, and the trajectory is irreversible. It may take time, but the outcome is inevitable.

Comments