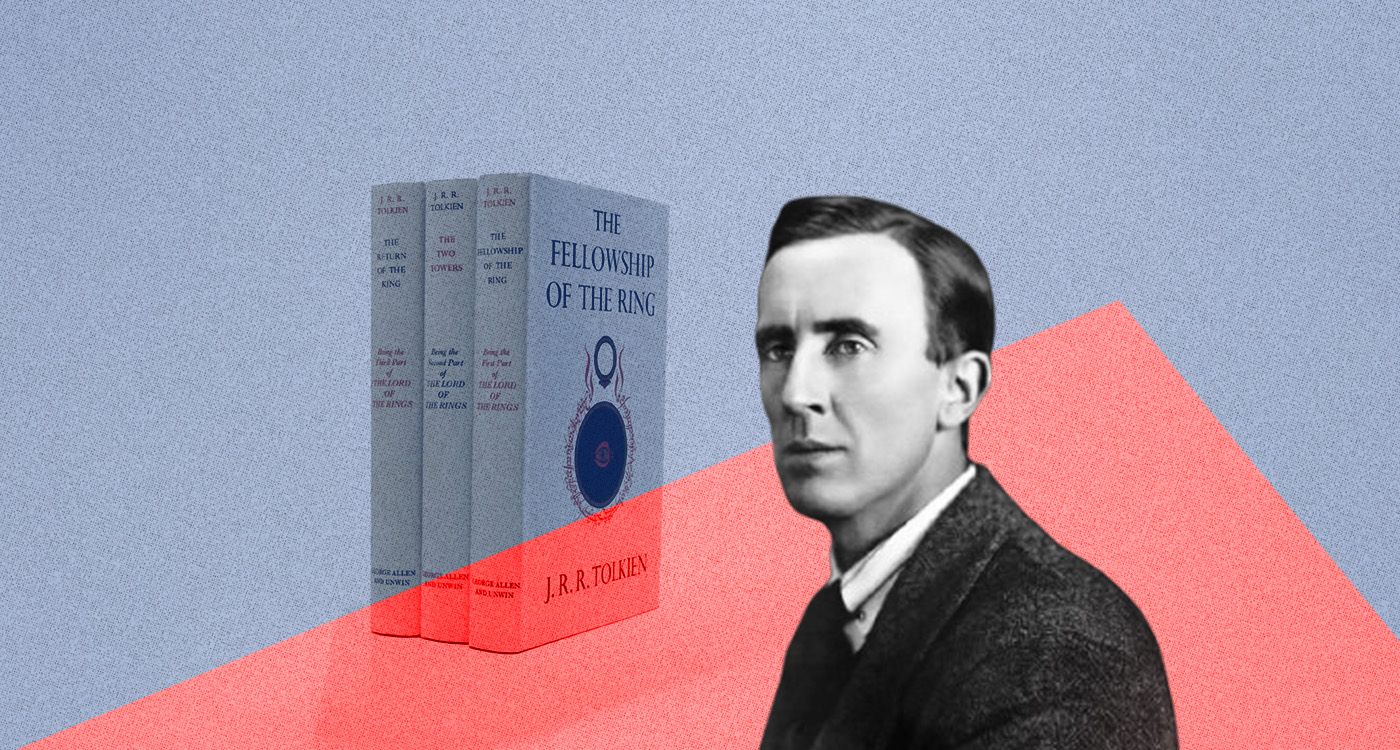

Before it became a cult saga, The Lord of the Rings was the fruit of solitary, patient and stubborn labor. For over 12 years, Tolkien wrote and typed his epic by hand, letter by letter, with just two fingers and an unshakable vision.

We tend to picture The Lord of the Rings as a towering monument of modern fantasy, which it is, unquestionably. But what we often forget is that this masterpiece is not only the product of an Oxford professor’s fertile imagination and passion for ancient languages. It was forged through relentless, profoundly manual work, carried out in solitude and with unyielding resolve. For more than a decade, J.R.R. Tolkien wrote, revised, recopied and then typed his work; not at the lightning speed of modern word processors, but slowly, painstakingly, with just two fingers.

In today’s age of nimble keyboards, such slowness seems obsolete. Yet that is precisely where The Lord of the Rings draws its singular breath: each word weighed, each sentence carved. Behind the magic of Middle-earth lies a silent epic: the story of a man alone before a blank page, advancing letter by letter with fierce determination.

Tolkien was not a professional writer in the conventional sense. A philologist and Oxford professor, he wrote early in the morning, late at night, between stacks of papers to grade and family life. Far from the pace now dictated by the publishing market, he worked like an artisan, setting his own tempo, even in his typing: two fingers, one on each hand, on a 1940s Royal typewriter. Speed was irrelevant, and rigor was everything. What might seem like a handicap became a tool for focus. Tolkien reread, crossed out and started again. He would draft in ink on lined paper, and only when satisfied would he type a stable version, then revise it yet again. Multiple drafts of each chapter still survive, covered in annotations and suggestions.

Twelve Years of Obsession and an Epic Forged in Slowness

In December 1937, just after The Hobbit was published, Tolkien began writing The Lord of the Rings. The journey would last until 1949; 12 years marked by doubts, interruptions and editorial disputes. Initially intended as a simple sequel for Bilbo, the project soon became sprawling. He invented languages, people and kingdoms. His correspondence reveals the toll: fatigue, anxiety and, above all, the sense that the end was always out of reach. Many times, he thought of abandoning it, but an inner vision pushed him to continue. Typing with two fingers slowed time, allowing him to immerse himself in the world he was building. Each typed page became a tangible fragment of Middle-earth.

One can picture him hunched over his machine, focused, striking each letter slowly, surrounded by stacks of papers and hand-drawn maps. The clack of the Royal typewriter was like a metronome. Slowness was his method, and the typewriter, far from being a mere tool, was part of the process. It gave official, physical form to a world born of heavily corrected, often illegible manuscripts. Despite his awkwardness, Tolkien long refused to let others type for him, insisting every page pass under his own fingers. Only in later years, and for certain copies, did he reluctantly accept help.

What stands out is his absolute fidelity to his own rhythm. He never sought to go faster, never to save time. It’s a quality that echoes through his work: heroes of Middle-earth travel on foot, slowly, at the cost of endless effort, far from shortcuts and sudden feats. In his world, adventure is an inner journey.

Tolkien quite literally lived his novel as he wrote it, in a stubborn dialogue with his typewriter and his two fingers: slow, but unwavering. Reading The Lord of the Rings today, one feels this density, this resistance to haste: nothing comes easily or gratuitously; everything is earned, page by page. Tolkien never typed fast, but he typed true. His dense, sometimes archaic style was born of effort, rigor and slowness.

In an age ruled by immediacy and the weary tyranny of the instant, his path reminds us that literature can also be born of patience and that masterpieces are acts of faith, built one keystroke at a time.

Comments