- Home

- Middle East

- Netanyahu’s Gaza Strategy: Ambiguity, Internal Divisions and Looming Chaos

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu looks on after a press conference at the Prime Minister’s Office in Jerusalem on August 10, 2025. ©AFP

As the war in Gaza enters its 22nd month, political and on the ground uncertainties continue to grow. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s recent statements highlight this growing strategic confusion. He says he wants to “take control of Gaza,” while specifying that Israel has “no intention of governing” the territory. This wording reflects a deep ambiguity, especially due to the ongoing confusion between the entire Gaza Strip and Gaza City, its capital, now seen as one of Hamas’s last strongholds.

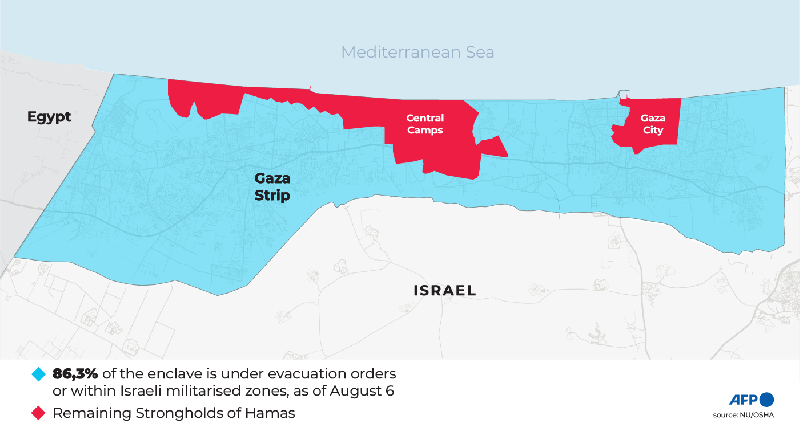

It’s important to distinguish between these two entities. The Gaza Strip, about 365 km², is a territory bordered by Israel, Egypt and the Mediterranean, with roughly 2.2 million people before the conflict. Gaza City, the largest city in the enclave, covers around 45 km² in the north and had nearly 750,000 residents. Despite the fighting, about 300,000 civilians remain trapped there today.

This ambiguity isn’t just a matter of terminology; it directly affects military operations, post-conflict political prospects and the dire humanitarian situation in the city.

At a press conference on Monday, Netanyahu stated that “the Israeli army controls 75% of the territory,” while demanding “the dismantling of the last Hamas strongholds, mainly located in Gaza City and certain central refugee camps,” such as Nuseirat, Bureij, Deir al-Balah, and al-Mawasi. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 86.3% of the enclave is either militarized by Israel or subject to evacuation orders still in effect.

Gaza City, along with its crowded neighborhoods, extensive tunnels and intricate underground networks, has become the main focus. Michael Milshtein, the head of the Palestinian Studies program at Tel Aviv University, estimates that Hamas’s military wing may number between 10,000 and 15,000 fighters in the city alone, many recently recruited – especially from the Zeitoun, Sabra and Shouja’iyya districts.

However, these numbers are difficult to verify, fueling significant uncertainty about Hamas’s actual military strength.

Netanyahu’s official plan is ambitious but remains unclear. He pledges a “swift operation” aimed at gaining full military control over the entire Gaza Strip and neutralizing Hamas’s last strongholds, while rejecting any long-term political or administrative governance. Last Thursday, the cabinet endorsed five basic terms to end the war: disarm Hamas, secure the return of all hostages (alive or dead) demilitarize the Gaza Strip, maintain Israeli security control over the area, and establish a civilian administration that is neither Hamas nor the Palestinian Authority.

This strategy lacks consensus within the Israeli government. While Netanyahu calls for military control without political occupation, ultranationalist ministers Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir demand a full and permanent occupation of the Gaza Strip. Although Chief of Staff Eyal Zamir has voiced concerns about the potentially catastrophic humanitarian consequences of such an operation, he nonetheless affirmed on Monday that the Israeli army is “capable of taking control of Gaza City, just as it did in Khan Younis and Rafah.”

Meanwhile, the humanitarian situation in Gaza City remains critical. Despite evacuation orders, many civilians remain, living in precarious conditions – often in tent camps or makeshift shelters – right in the heart of the conflict zone. Humanitarian aid struggles to reach the population, largely due to Israel’s refusal to allow the United Nations to manage distribution, fearing it could benefit Hamas. Instead, Israel has entrusted this task to the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation, supported by both Israel and the United States. This initiative, sharply criticized by NGOs, has been accused of militarizing aid and described by Human Rights Watch as a “deadly trap” for civilians.

Several key questions remain unresolved: What exactly does Netanyahu mean by “control of Gaza?” Is he referring solely to Gaza City or the entire territory? How can military control be maintained without political governance in a devastated region lacking functional institutions and reliable political representation? And most importantly, if Hamas is truly weakened, how does it still manage to maintain its armed presence and continue operations despite the ongoing Israeli offensive?

Overall, the situation in Gaza remains a complex web of uncertainties, ambiguities and internal tensions – both Israeli and Palestinian – that hinder any clear short- or medium-term prospects. Meanwhile, civilians continue to endure suffering and death amid ongoing strikes, hunger and a dire lack of medical care.

Read more

Comments