Sexuality isn’t something that just happens. It begins to take shape from birth, through the body, language and family history. From breastfeeding to the Oedipus complex, psychoanalysis sheds light on the formative stages of desire and sexual identity.

Human sexuality is a journey. It doesn’t suddenly surface at adolescence or with a first sexual experience. It develops from birth, woven over time through sensations, taboos, fantasies, emotional attachments and inner conflicts. The libido, understood as the energy of desire, begins to form in early childhood, gradually finding shape, attachment and movement through both body and mind.

Human sexuality is therefore also psychological. What is often (wrongly) described as a “sexual instinct” is in fact a complex, conflict-ridden and deeply individual process.

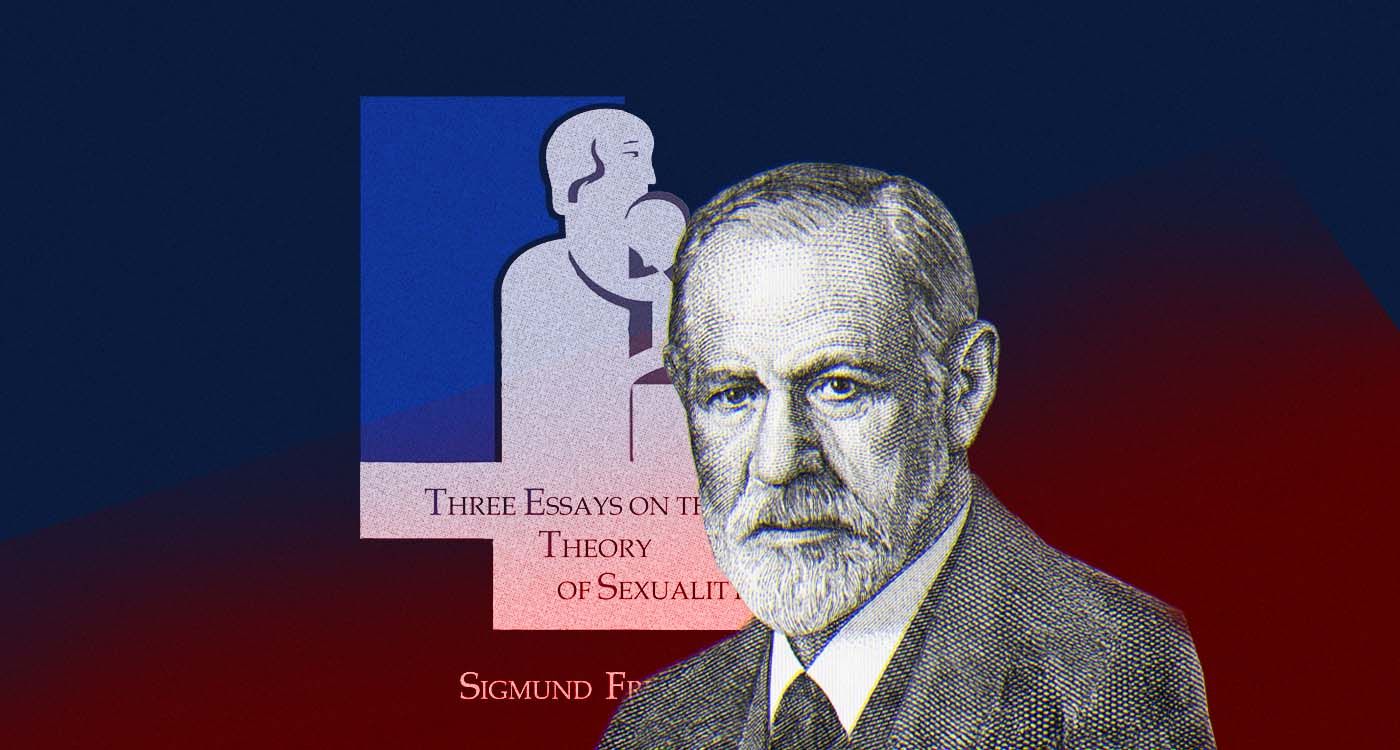

In Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, Freud outlines a series of phases through which the libido is directed toward different parts of the body. The first, known as the oral phase, places the mouth at the center of early libidinal life. The infant suckles, chews and bites, all actions charged with intensity, where pleasure and anxiety are intertwined. The mother, or her substitute, becomes the first object of love. It is through her that the world is first encountered, through both satisfaction and frustration.

The anal phase follows, between the ages of one and three, marked by what is commonly known as toilet training. This stage centers on the dynamics of retention and release, control and letting go. The stakes are not only physical: the child begins to discover the power to say no, to hold back or to give, to please or to defy. What is often wrongly dismissed as mere “tantrums” is in fact a desire continuing to seek expression.

Between the ages of three and six, the phallic phase emerges. The child, whether boy or girl, explores their genitals, becomes curious and begins to ask questions. They become aware of sexual difference, but most importantly, they confront it in a fantasized way. This is the time of the Oedipus complex, often described as the boy’s imagined desire for his mother and his view of the father as a rival, while the girl turns away from the mother and directs her desire toward the father. Emotions at this stage are marked by deep ambivalence.

This stage plays a key role in shaping identity. It’s where early gender positioning takes root and sexual identification begins to form. Children often model themselves on the parent of the same sex, while directing their desire toward the other. But these identifications are rarely clear-cut. A boy may strongly identify with his mother, just as a girl might with her father. The unconscious doesn’t follow straight lines.

From about age six, the latency period brings a relative calm. Sexual impulses settle down without disappearing. They shift toward socially valued activities like learning, friendships, sports or the arts. This is when Oedipal desires are repressed and libido is sublimated. The individual begins to engage with reality and negotiate it. But if this stage is disrupted, if Oedipal conflicts have not found symbolic resolution, future relationships, both emotional and sexual, may be compromised.

In adolescence, the genital phase begins. The body changes and sexual drives reactivate. But this sexuality isn’t simply a final stage, it’s a reworking of everything experienced in childhood, returning in new forms. When desires manage to find an external object beyond the family, old conflicts can still resurface. An adolescent whose impulses are suppressed, for example, may replay unresolved childhood scenarios when their urges are blocked.

It is important to emphasize that sexual maturity does not depend solely on hormones, but on how earlier psychosexual stages have been experienced. Being sexually active does not necessarily mean being psychologically ready for connection, for encountering another person or for shared desire. Sometimes, the body leads the mind and can even overwhelm it.

Freud introduced a crucial concept that is often overlooked: the early presence of psychic bisexuality. Every human being, regardless of anatomical sex, carries both masculine and feminine aspects within. These dimensions are present from childhood in dreams, play and desires. They do not cancel each other out but coexist, sometimes in harmony and sometimes in tension. This bisexuality is not about sexual orientation but a structural reality. A boy’s admiration for his mother and a girl’s rivalry with her father, all part of a mirror-like interplay, contribute to the formation of an originally multiple sexuality. Culture, society and social roles may restrict or channel this potential, but never completely erase it.

Psychoanalysis reveals that sexuality revolves around symbolization. The body alone does not speak; a person comes to understand their sexual identity through the gaze of others, the words we hear and the expectations we sense. Even before saying a word, the child finds themselves spoken for: labeled, named and woven into a story.

Biological sex serves only as a starting point. What truly shapes identity are the sexual signifiers, the way one is seen, treated or desired as a girl or a boy, or told they are “too much of this” or “not enough of that.” The unconscious forms within this network of words, gestures and unspoken rules passed down without awareness.

No two people are identical, nor are any two sexualities alike. Every individual story is subjective and therefore unique. What one person experiences as a gesture of affection may be perceived by another as control. The same action can be remembered as love or as rejection. It is not reality itself that shapes us, but the way it has been fantasized, interpreted and absorbed.

Within this intricate weave, psychoanalysis offers a compass. It does not prescribe what sexuality ought to be but seeks to understand how it has taken shape, through which wounds, attachments and repressions.

The body we are born into is a starting point, not a destination. It is through the body, and at times in tension with it, that the subject invents a way of being in the world, of forming bonds, of loving.

Comments