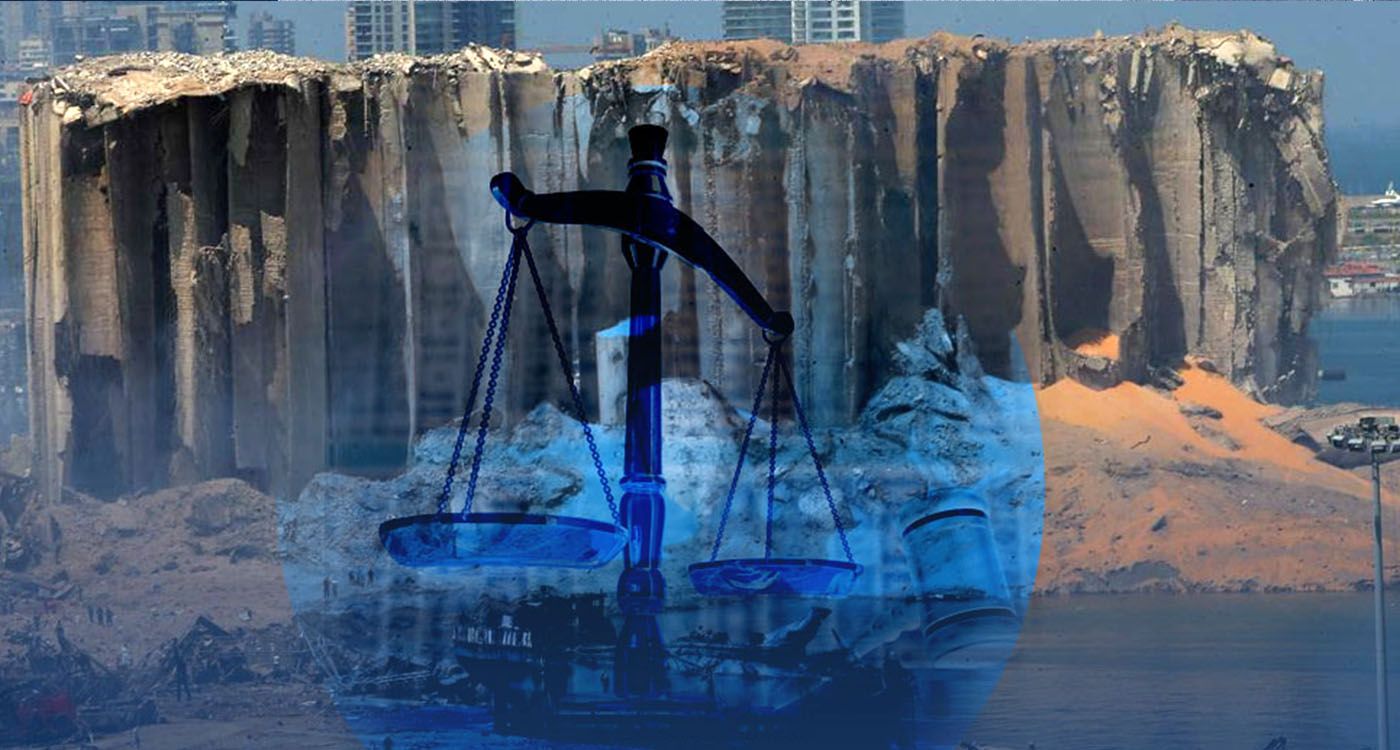

Five long years. Five years since the explosion on August 4, 2020, that mushroom-shaped cloud that swallowed the capital, crushed hundreds of lives, and left a nation in shock. Yet in Beirut, life has gone on as if nothing happened. As if more than 240 people had not died, as if over 7,000 had not been wounded, and as if the country were not facing a series of economic, political and security-related crises.

At a glance, the city looks alive: terraces are crowded, ruins have faded beneath new real estate projects, and official statements rarely mention ammonium nitrate anymore.

But beneath this fragile facade, one question weighs heavily on survivors, the families of hundreds of victims and thousands more injured: Where does the investigation into the Beirut port explosion stand? And more importantly, how much longer will the truth be kept from the public?

Even more so because the newly elected president, Joseph Aoun, and Prime Minister Nawaf Salam, shortly after forming the government, pledged to “shed full light on the case.” This commitment was reiterated on July 31, when the president addressed the nation on the occasion of the army’s national day.

“Taboos are being broken, immunities lifted, and those involved in the August 4 explosion case will be prosecuted and jailed without any protection other than the law,” President Aoun declared, emphasizing that “this is the start of a long process of accountability, with judges as its only guarantors.”

While this message offers hope, it faces a significant hurdle: several ministers and MPs implicated in the case are questioning Judge Bitar’s authority to prosecute them. They maintain that the High Court – tasked with trying presidents, prime ministers and ministers – should hear their cases, not an ordinary court. Some legal experts dismiss this argument, pointing instead to the principle of probable intent.

A Hindered Restart

In January 2025, an unexpected twist: after a two-year pause, Judge Tarek Bitar resumed control of the investigation. His sudden return sent ripples through the judiciary. He quickly moved to summon several senior officials, including former General Security chief Abbas Ibrahim and former State Security Director General Tony Saliba. Some complied with the summons. Others, however, chose silence, most notably two key figures: MP and former Public Works Minister Ghazi Zeaiter and Court of Cassation Prosecutor General Ghassan Oueidat.

The former was due to appear most recently on July 18, 2025, following multiple prior refusals. This time, he was officially notified. The latter refused to accept notification for his scheduled hearing on July 21. Neither is expected to appear, according to a source close to the case.

On July 15, a court bailiff acting on behalf of Judge Jamal Hajjar, who succeeded Judge Oueidat, arrived at Oueidat’s residence in Shehim to deliver the summons. The recipient accepted the document but refused to sign it, stating in a handwritten note added to the case file that he did not recognize Judge Bitar’s authority or legitimacy. Using language that was more political than legal, he even described the investigative judge in the port explosion case as an “invalid party” and called on the prosecutor general to file a complaint against him.

And yet, if the notification procedures comply with the law, which seems to be the case according to judicial sources interviewed by This is Beirut, the investigating judge does not need to secure their physical presence. He can consider the notification effective, indict them in absentia, and issue the indictment after submitting it to the Prosecutor General at the Court of Cassation, who will then provide a non-binding opinion.

A Doomed Investigation?

How did things come to this point? To understand the current deadlock, it is necessary to go back to the beginnings of the investigation.

The first judge assigned to this high-profile case was Fadi Sawan, who began work in 2020 by seeking to question several former ministers: Ali Hassan Khalil, Ghazi Zeaiter and Youssef Fenianos. Political pressure quickly followed. Two ministers filed a challenge, citing a “legitimate suspicion” of bias. In February 2021, Judge Sawan was removed from the case by the Court of Cassation.

Tarek Bitar then took over the investigation. He summoned ministers, security chiefs, former prime ministers and even President Michel Aoun with a written list of questions. That’s when the deadlock deepened. Legal challenges flooded in, and the investigation ground to a halt. In January 2023, Ghassan Oueidat, despite being implicated himself, declared himself competent and ordered the release of the 17 detainees connected to the case. He even launched proceedings against the investigating judge. The investigation was suspended, leaving Judge Bitar sidelined for nearly two years.

Public authorities have also been carrying out a methodical sabotage, blocking judicial appointments, refusing to appear and using legal maneuvers.

Today, however, a long-standing barrier appears to be breaking after eight years: judicial appointments, the last of which dated back to 2017. On July 30, the Higher Judicial Council (HJC) approved the appointments and transfers of 524 judges before forwarding the list to Justice Minister Adel Nassar. At this stage, the minister can either approve the nominations or raise objections.

In the second scenario, the HJC faces two options: either take the minister’s objections into account and amend the proposal, or approve it as submitted by a majority of seven out of the ten council members.

Next, the signatures of the Minister of Defense, the Minister of Finance, the Prime Minister and the President of the Republic will also be required.

These appointments are particularly crucial because they allow for the reformation of the plenary assembly of the Court of Cassation, the only body authorized to rule on appeals involving Judge Bitar. However, this assembly has been dysfunctional since January 2022 due to a lack of quorum following the retirement of several members.

In the past, the HJC repeatedly prepared appointment proposals, but these were stalled for months at the Ministry of Finance. The former Minister, Youssef Khalil, an ally of Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri, refused to sign the document, citing “an imbalance and ambiguity in the text.”

The Crime Scene: Unresolved and Unexplained

At the center of this case is a stockpile of 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate, stored for six years in a warehouse at the port. The Moldovan-flagged vessel Rhosus, chartered by Russo-Cypriot businessman Igor Grechushkin, was supposed to deliver the cargo to Mozambique. Yet since 2020, no one has been able to reliably trace the funding routes, logistical responsibilities or the final beneficiaries.

Shell companies, suspicions of Lebanese and Syrian networks, and goods potentially diverted for military or industrial use all remain unclear. No authority has yet had the courage to illuminate this shadowy area. To date, no scientifically confirmed explanation has been accepted to clarify the causes of the blast, which experts say should be relatively simple to determine.

In response to the failure of local justice, several legal proceedings have been initiated abroad, both by the Beirut Bar Association’s prosecution office and by victims with dual nationality. These actions involve countries such as France, Germany and the United Kingdom. Non-governmental organizations including Human Rights Watch, Legal Action Worldwide and Amnesty International have also called for an international investigation.

Although some progress has been achieved thanks to the tireless efforts of the prosecution office and the victims’ families, the international community remains unresponsive. Despite repeated calls from Judge Bitar for cooperation, including the provision of satellite images, expert reports and other evidence, no response has been forthcoming.

For the judge, a resolution remains possible. If he can overcome the final procedural obstacles, validate the refused notifications and issue his indictment, a critical milestone will have been reached: formal charges. What follows will then depend on the state, or what is left of it.

If this investigation, like previous high-profile cases in Lebanon, has taught us anything, it is that truth hinges more on political will than on judicial process.

Comments