The Théâtre de la Ville in Paris recently hosted a remarkable revival of Bérénice, boldly reinterpreted by Romeo Castellucci and featuring Isabelle Huppert. This free adaptation of Racine’s tragedy offers a deep, sensory exploration of the character’s solitude, breaking away from classical theater conventions.

The Italian director, known for his expertise in visual and sensory theater and inspired by his knowledge of painting, scenography and stage design, took Racine’s tragedy and transformed it into a fully contemporary interpretation. The production centers on the heroine’s intense pain, creating an immersive experience far removed from the traditional staging of the play. Portrayed by Isabelle Huppert, Bérénice embodies the face of absolute loneliness, in a performance where the voice – both spoken and amplified through sound – becomes a central tool beyond mere words. This is a monologue delivered in solitude, stripped of the original play’s dialogue. The actress confronts the heavy, heartbreaking, eternal pain of passion.

Bérénice, a first-century princess, remains one of the most compelling figures from antiquity, inspiring countless artists through the ages. Her tragic love affair with Roman Emperor Titus reflects the timeless conflict between passionate love and the demands of reason – especially those of state. In 1670, Jean Racine made this story the subject of a five-act tragedy entirely written in alexandrine verse – 1,506 lines in total – dramatizing an inevitable separation as a universal human drama. Romeo Castellucci revisits this iconic work, focusing on Bérénice’s inner solitude – a woman abandoned yet capable of ultimate surrender. True to his signature image-driven theater style, he entrusts the intense role to Huppert, a formidable contemporary stage actress. In this stripped-down, powerful staging, words nearly fade, syllables drop into silence under their emotional weight, making the mythic human despair palpable.

Set to an electronic soundtrack by Scott Gibbons, emotions are distilled through music. The composer demystifies speech, drawing us into a hypnotic, dreamlike world. Scientific percentages flash on a large screen, reminding the audience of the fleeting nature of the human existence. In this gripping set design, the actress begins from the back of the stage, shielded from the audience and reality by a translucent screen. Bathed in the deep blue of a woman’s life, the black of despair bursts forth. Desperate, she moves forward, toward her fate, crossing the majestic, sumptuous stage...

Huppert embodies Bérénice. She approaches Racine’s text like lines on a cinema screen – attacking, taming, articulating each syllable, playing with rhythm and sounds, leaving some words hanging mid-phrase, suspending gestures on the edge of self-forgetfulness. She lets silence speak; the audience hangs on her lips, her slightest movements. Her motions are modern, far from the calculated gestures of a princess. All codes, dialogues and characters fall away. Yet she holds her posture– upright, unyielding, truthful in her precision. The audience witnesses a long, unending lament from Bérénice, a solitary monologue. The actress clings to Racine’s alexandrines as her stage anchor. Gradually, she and the text become one. Through these words, she transforms back into a woman among all women, like a Cinderella in rags, alone and distant from her beloved. She lets herself fall and fall again, descending into the depths of despair – then returns.

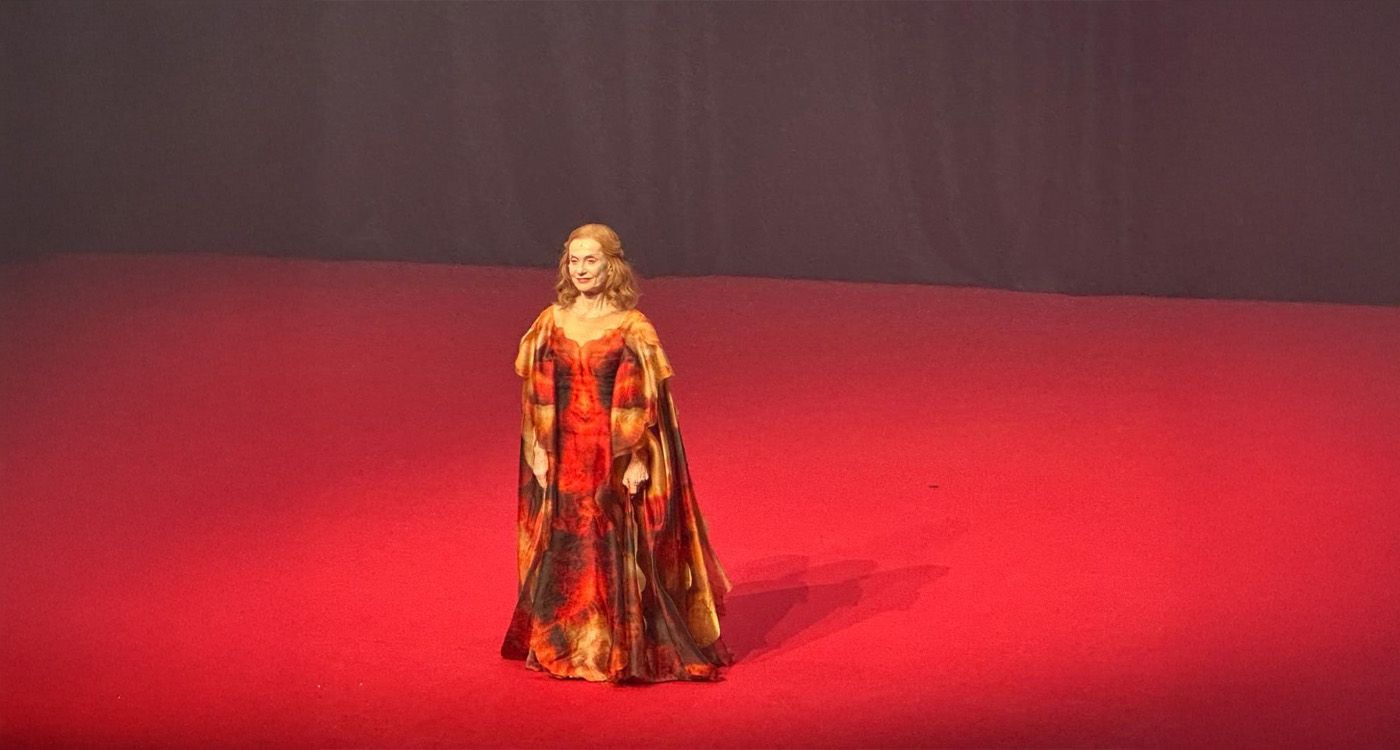

In her grand final act, she restrains herself, standing tall and proud despite interrupted words and the pain that threatens her composure. Standing in costumes by Iris Van Herpen – known for bridging fashion, nature and science – Huppert courageously embraces a stage design featuring giant flowers shedding their petals one by one. The play’s final moment is a staging masterstroke: the translucent curtain rises. It remains unclear whether it’s Bérénice or the actress speaking – two women separated by centuries, between imagination and reality, past and present, in a modest yet raw unveiling. The audience is instantly transported into a cinematic world, as if in a blink – a palpable homage. She, speaking for all women, demands a moment of reprieve between shadows and light, reminiscent of David Lynch’s The Elephant Man. The voyeuristic spectators watch breathless, eyes wide open, until the very last moment.

This production bears Castellucci’s unmistakable signature: contemporary, full of shadows and light, combining aesthetics and rigor. The supporting cast, often in the shadows, performs a precise choreography, their stage appearances like the Stations of the Cross. Racine’s presence is undeniable yet limited: Castellucci focuses on Bérénice’s sole monologue, with a few additional lines, embodied through a theater of body, voice and bare words by Huppert, alone on stage.

The standing ovation lasts for minutes, and Huppert takes a few quick, controlled steps backward for her final bow – perhaps restrained by memories of her role as Mary Stuart, performed in the same intimate Théâtre de la Ville venue a year earlier, in Mary Said What She Said, directed by Robert Wilson. Castellucci’s Bérénice, performed by Huppert, is a unique act rooted in profound solitude – a daring staging choice and a brave performance by an intrepid actress.

Comments