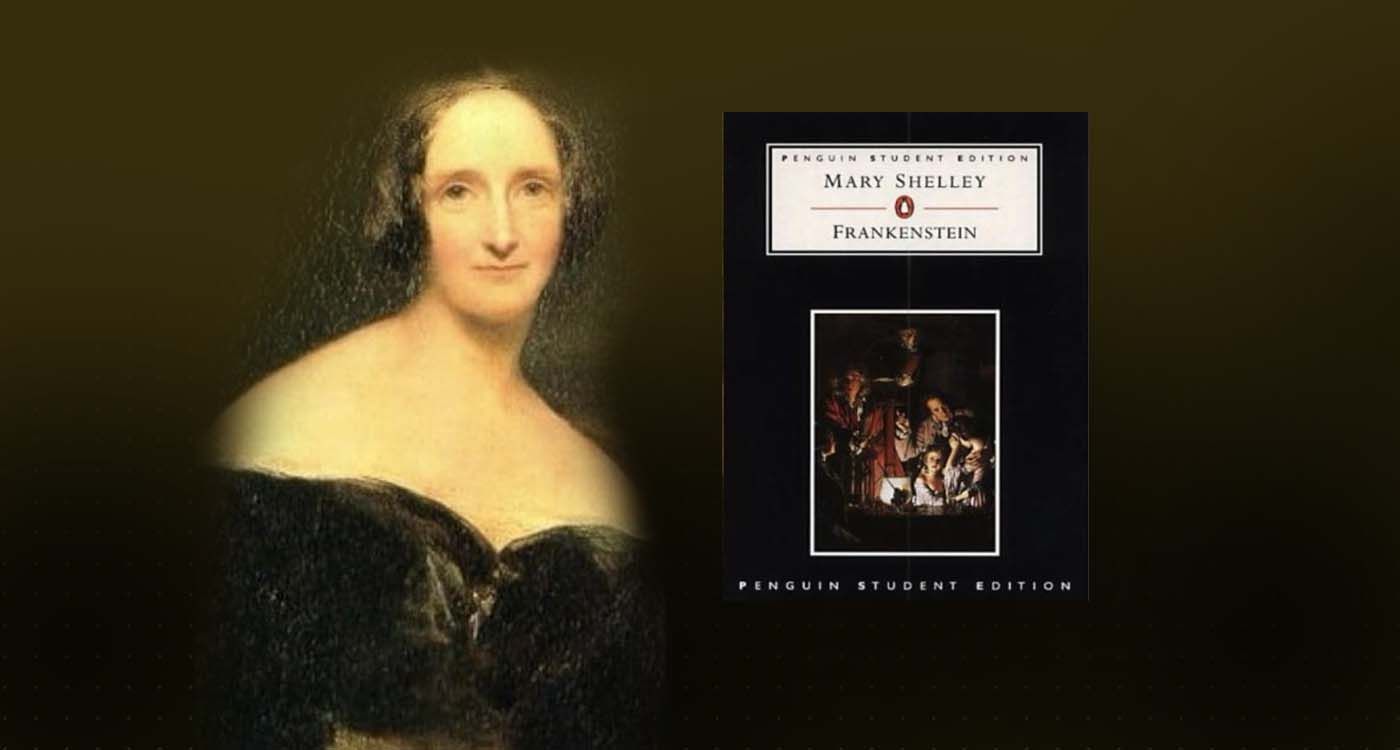

Born of a wager made during a stormy night at Villa Diodati, Frankenstein took shape under the pen of Mary Shelley, barely 18 years old. Since then, the novel has continued to challenge our views on creation, loneliness and the limits of science.

Summer of 1816 was not actually a summer. Across Europe, skies remained dark, veiled by the ash of Mount Tambora, which had erupted the year before. In Geneva, it rained relentlessly, lightning flashing over the shores of Lake Leman. It was in this strange atmosphere that a small group of English literary exiles found themselves confined indoors. Among them were poet Lord Byron, young writer Percy Shelley and his companion Mary, daughter of philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft. Mary was only 18. She observed, listened, read and wrote in silence. From that moment, the idea for a novel was born – Frankenstein – one that continues to haunt us two centuries later.

The setting was Villa Diodati, on the lake’s edge. Conversations drifted from science to life and death, from electricity to poetry. Evenings were filled with readings of gothic tales and spirited debates. One night, Byron challenged his guests to write a ghost story. The game was on. It took Mary several nights to find inspiration. She later described a kind of vision: a scientist leaning over an inanimate body, slowly reanimated by electricity. It wasn’t a dream, she said, but an image that emerged in the liminal space between sleep and waking. Within weeks, she began writing. The book was published in 1818, under the title Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus, anonymously. She was just 20.

A Creature More Human Than It Looks

Frankenstein is often labeled a mere horror novel, but it’s much more than that. It delves into science, yes, but also into solitude, rejection and responsibility. Victor Frankenstein, the scientist, creates a being he immediately abandons. He is no hero, but rather a man overwhelmed by his own ambition. His creature – so often referred to as “the monster” – is first and foremost a sensitive being, eager for love and understanding. Rejected by all, it turns violent only after enduring humiliation and exclusion. The novel never quite reveals who the real monster is: the man or his creation.

The creature is also a reflection of its time. It is born in a world where science is advancing rapidly, where electricity is being tested on corpses, and where many dream of defying death. Victor Frankenstein seeks to unlock the secrets of life, as many scientists of the era did. But Mary Shelley also warns of the dangers of such ambition: pride, lack of accountability and indifference to what we bring into the world. Without knowing it, she sketched the figure of the modern scientist – and the unease that comes with it.

At the heart of the novel lies an open question: Who is more monstrous? The one who kills or the one who rejects? The creature learns to read, speak and feel. Yet it has no name, no place in the world. It is cast out for its difference. What frightens us in this story is not horror itself, but what it reveals about our tendency to deny what we create.

Shelley wrote other works, but Frankenstein is the one that endured. It has been adapted, retold and transformed into a lasting icon of modern culture.

We see it in film, in debates on bioethics, in conversations about artificial intelligence. What it says about science, humanity and the lines we cross without thinking remains deeply relevant.

And yet, it all began with a game, a thunderstorm and a young but watchful mind. What Shelley gave us is not just a chilling creature, but a lasting unease: the anxiety of a world that creates without measure, that discards what doesn’t fit, and that risks forgetting what it means to be human.

Did you know? Frankenstein’s first film adaptation dates back to 1910

Long before Hollywood turned Frankenstein into an icon, the novel was first adapted for the screen in 1910 by Edison Studios (founded by Thomas Edison himself). This 16-minute silent short film – now restored – depicted the creature as an almost magical being emerging from a cauldron. Though far from faithful to the novel, it laid the groundwork for the visual language of horror cinema that would follow for over a century.

Comments