Around 700,000 years ago, two human species diverged from a common ancestor, each evolving separately into distinct forms adapted to the conditions of their respective continents. The African species, known as Homo sapiens, eventually spread across the globe, while the European species, the Neanderthals, disappeared under mysterious circumstances.

Our planet has been home to various species of the Homo genus, with fossil evidence dating back around 2.8 million years. Among these, two species stand out as the closest relatives to modern humans: the European Homo neanderthalensis and the African Homo sapiens.

About 660,000 years ago, two branches of the Homo genus diverged from a common ancestor: one gave rise to Homo sapiens in Africa, and the other to Homo denisovaensis in Asia and Homo neanderthalensis in Europe. With the extinction of the latter two species, all of today’s human population traces its lineage back to African Homo sapiens, most likely originating from a single group that migrated out of Africa around 60,000 years ago.

The Two Species

The European species, Homo neanderthalensis, and the African species, Homo sapiens, evolved independently and in parallel on their respective continents between 500,000 and 300,000 years ago. The oldest known Homo sapiens fossils date back around 300,000 years, while Neanderthal remains have been found as far back as 430,000 years, notably at the Sima de los Huesos site in Spain.

The name sapiens means “wise,” while Neanderthal derives from German, meaning “valley of the new man.” However, this is purely coincidental—the valley had already borne that name long before the species was identified there in August 1856 and subsequently named after the site.

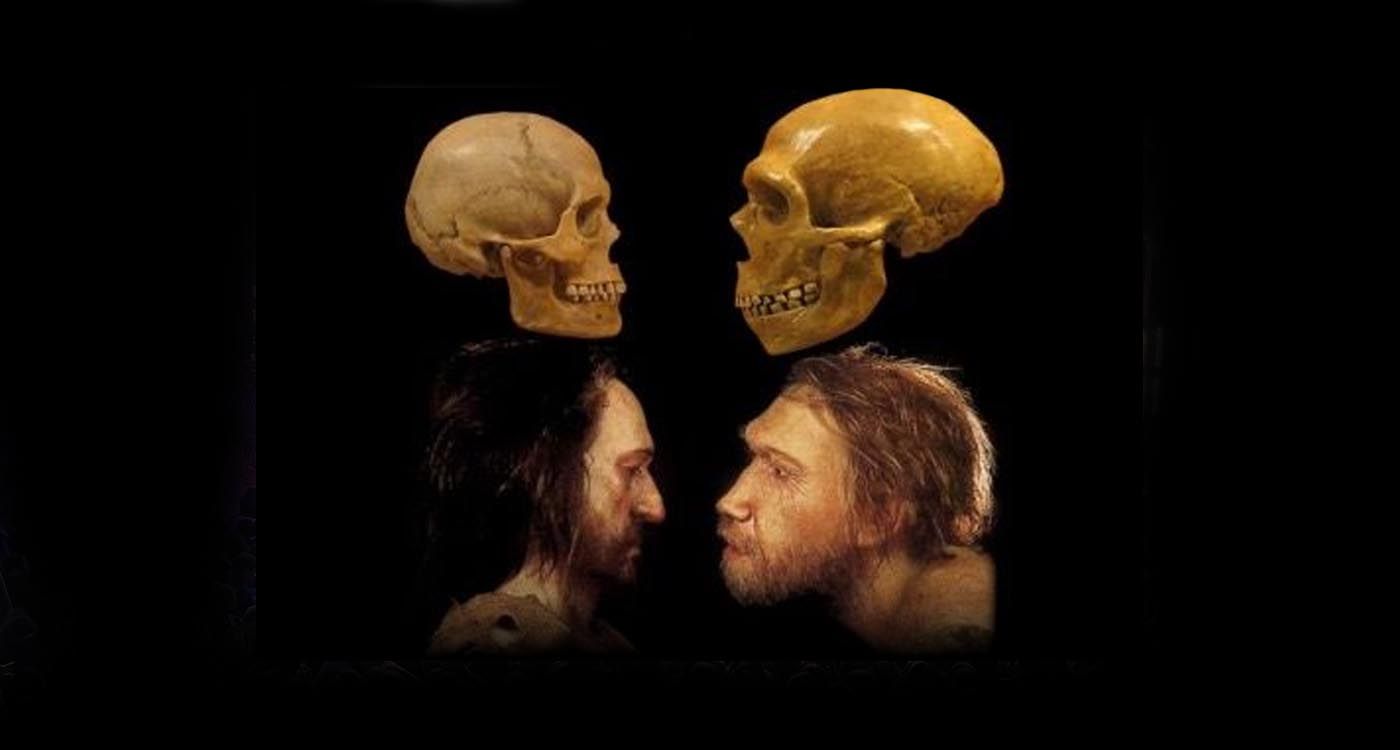

Defining Traits of the Two Species

The European species evolved into a sturdy, thick-boned, heavyset, and slightly stocky form, better adapted to the cold climate of its continent. Its massive build and prominent muscle attachments indicate considerable physical strength. A pronounced brow ridge—or supraorbital torus—gave it a distinctive appearance and, combined with the elongated shape of the skull, highlighted the clearest contrast with Homo sapiens.

On average, Neanderthal males stood around 165 cm tall and weighed about 90 kg, while females measured approximately 155 cm and weighed around 70 kg. Individuals taller than 190 cm were extremely rare.

Neanderthals showed the ability for speech and practiced group solidarity, burial customs, and funerary rituals. Their genetic predisposition for language is supported by DNA samples recovered from the El Sidrón cave in Spain, which revealed the presence of the FOXP2 gene—associated with the development of brain regions involved in language.

The African species followed its own path of development, evolving into a slender, lean, and lightweight form with a more rounded skull. It embarked on several migrations out of Africa, but these earlier waves did not endure. Only the final migration succeeded—and it was this small group of Homo sapiens that ultimately populated the planet.

Surprisingly, humans in Europe and the Levant—despite being better adapted to cold climates—disappeared following the arrival of African groups. The descendants of these African populations eventually spread across every continent, even reaching the Arctic ice caps. Why Neanderthals vanished after coexisting with Homo sapiens for more than 20,000 years remains an enduring mystery. Yet Neanderthals were not the only species to disappear; other human species, including the Denisovans and earlier “archaic” Homo sapiens from previous migrations out of Africa, also went extinct.

First Departures from Africa

Homo neanderthalensis, the European human species, left the north following an ice age that began around 120,000 years ago. Upon reaching the Levant, they encountered “archaic” Homo sapiens populations, who were already present in both the Levant and Europe. Evidence of their existence comes from excavations at sites such as Apidima Cave in the Peloponnese, Greece, and Misliya Cave on Mount Carmel, Israel. The former yielded a Homo sapiens fossil dated to approximately 210,000 years ago; the latter, a partial upper jawbone estimated at around 185,000 years old.

These early waves of Homo sapiens migrating out of Africa did not contribute to the genetic heritage of modern humans. They failed to survive the repeated glacial periods and were eventually supplanted by the Neanderthals, who were far better adapted to the cold.

The Last Departure from Africa

Only the migration out of Africa between 65,000 and 45,000 years ago achieved true global success. According to one hypothesis, it began with a very small group—around 150 individuals—who would go on to populate all of Eurasia, and eventually the Americas and Oceania.

This idea is supported by genetic evidence, specifically mitochondrial DNA, inherited maternally, and the Y chromosome, inherited paternally. Because these two parts of the genome do not undergo recombination during fertilization, they allow us to trace all of present-day humanity back to a single African woman, known as Eve, and a single African man.

The planet was gradually populated by this small group of Africans through successive waves of migration. They spread into Asia, likely following its southern edge, and into Europe from their Levantine cradle. Around 50,000 years ago, in the Levant, Neanderthals and Homo sapiens are believed to have interbred—just before the latter expanded across all continents.

This mixed Homo sapiens population is the one that reached both Australia and Europe around 50,000 years ago, as indicated by the genetic clock, which tracks mutations accumulated over time. Fossil evidence supports this, including human remains found at Lake Mungo in southern Australia and Mandrin Cave in the Rhône Valley.

The Levantine Cradle

Findings from Mandrin Cave have pushed back the presence of “modern” Homo sapiens—those from the most recent migration out of Africa—in northwestern Europe to around 54,000 years ago. Meanwhile, Neanderthals are believed to have disappeared only about 30,000 years ago. This means the two species coexisted for tens of thousands of years, allowing time to exchange ideas, cold-adaptation techniques, knowledge—and even genes.

Today, all Europeans, Levantines, and Asians carry between 1.8% and 2.6% Neanderthal DNA. Collectively, as much as 20% of the Neanderthal genome survives across the modern human gene pool. After leaving Africa around 60,000 years ago, Homo sapiens lived alongside Homo neanderthalensis in the Levant before continuing their colonization of the rest of the planet.

Human remains from Bacho Kiro Cave in Bulgaria have been found alongside sharp flakes typical of European Neanderthals, as well as retouched blades characteristic of Levantine Homo sapiens and the material culture known as the “Initial Upper Paleolithic” (50,000 to 40,000 years ago). The lithic industry at Bacho Kiro clearly derives from the Levant, as evidenced by similar tools and fossils discovered at Ksar Akil in the Antelias Valley, in the heart of Mount Lebanon.

The Levant served as a crossroads for the exchange of genes and ideas that laid the foundation for the Aurignacian culture (47,000 to 41,000 years ago) and the Mousterian culture (which ended around 35,000 years ago). Successive waves of prehistoric Levantine migrations continued to reshape Europe’s genetic and cultural landscape.

Comments