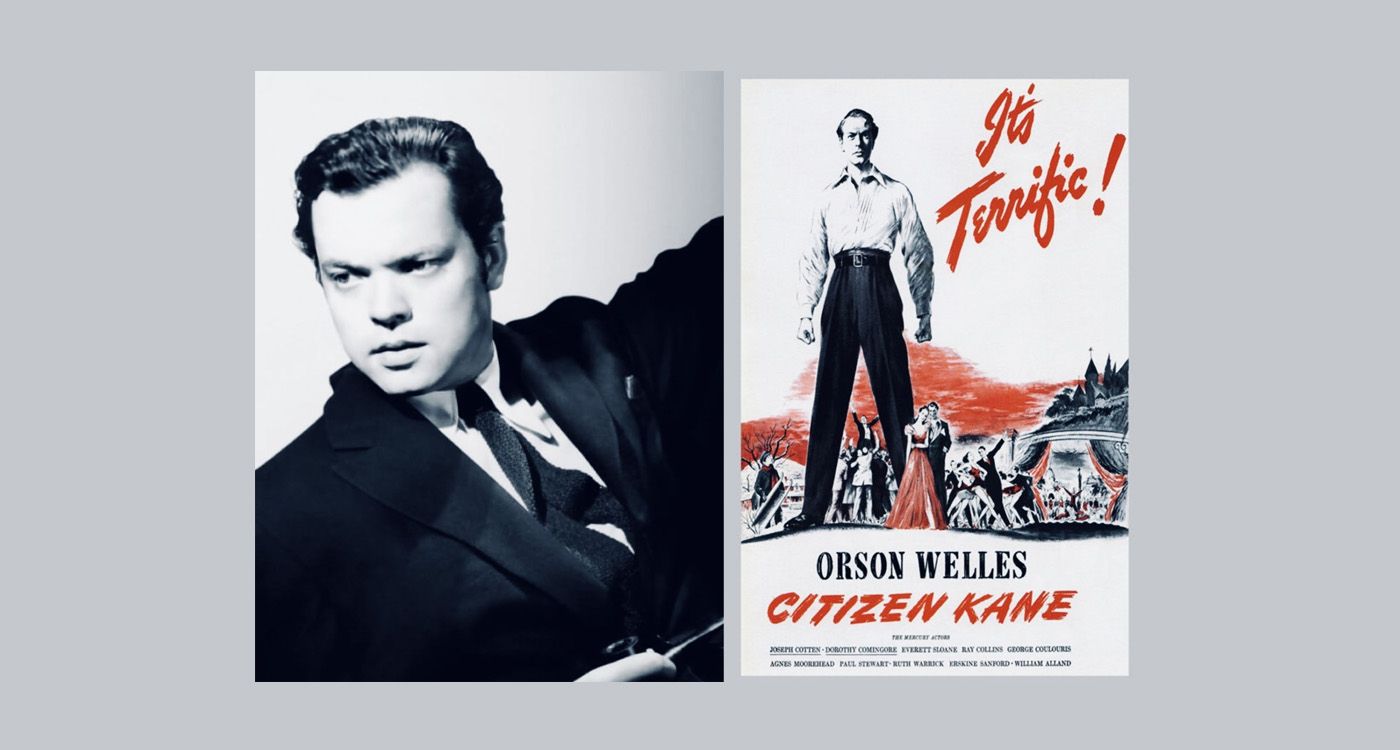

At 25 years old, Orson Welles reinvented cinema with Citizen Kane. Born of unprecedented creative freedom, media revenge, and breathtaking visual invention, this groundbreaking film is a declaration of war against conventional cinema.

What’s being told here is no myth. Orson Welles really was 25 when he shot Citizen Kane. He had never directed a film before, but had already caused a sensation in 1938 with his radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds, so realistic it panicked thousands of Americans. A prodigy to some, a fraud to others, he fascinated everyone. The RKO studio, in search of prestige, offered him a unique contract: total freedom over the script, casting, and editing. Welles could do whatever he wanted—and he took full advantage.

From that freedom came Citizen Kane, the portrait of a press tycoon, Charles Foster Kane, told from the moment of his death. His last word: “Rosebud.” A journalist tries to uncover the meaning of this mysterious word by interviewing those who knew him. Each one gives a different, often contradictory version. Kane remains elusive. The film, constructed like a puzzle, becomes a riddle—an impossible investigation of a man who defies any clear summary.

Behind Kane, many recognized William Randolph Hearst, the powerful newspaper magnate. Welles played on the resemblance. Kane’s extravagant castle, Xanadu, recalls Hearst’s own grand residence, San Simeon, on the California coast—a vast estate filled with artworks, empty rooms, and endless corridors. A place outside of time, designed to dazzle, but that becomes the stage for crushing solitude. In the film, the more the set expands, the more the character shrinks. Every room feels too big for the man wandering through it. It’s the perfect image of someone who conquered everything—except himself. Political ambition, failed loves, boundless pride—Welles pushes every lever to the limit. Hearst, furious, tried to suppress the film, threatened RKO, rallied his newspapers, and even offered to buy up all the copies to destroy them. The studio refused. The film was saved—barely.

To create such a portrait, the form had to match the substance. Welles partnered with Herman J. Mankiewicz, a once-brilliant journalist, caustic and bitter, worn down by alcohol and Hollywood cynicism. Together they wrote a radically new screenplay. There’s no linear chronology: the story unfolds in flashbacks and scattered, sometimes contradictory, memories. There’s no clear message: the film doesn’t judge or condemn—it asks questions. And there’s no heroic figure: Kane is neither a model nor a villain, but a man deeply fractured. The film resists any definitive interpretation. It embraces ambiguity, doubt, and a multiplicity of perspectives. That’s what gives it its richness and modernity.

But the true revolution of Citizen Kane lies in the image. With cinematographer Gregg Toland, Welles invented a new cinematic language. Together, they dared everything: high angles, low angles, extreme depth of field, tight framing, tracking shots that pass through walls. The camera seems free, unbound, alive. Lighting and shadows heighten the tension, faces are carved out by the light. Every shot is composed to reveal power, secrets, or solitude. Even the sound is sculpted: voices fade away, silences weigh heavy, noises become characters in their own right. Citizen Kane experiments boldly without ever losing the viewer.

Filming was tense. Hearst kept up the pressure. The press remained silent. The studio grew anxious. But Welles stood firm. He played Kane himself, his appearance transformed by makeup at each stage of the character’s life. He directed with surgical precision, demanding dozens of takes and fine-tuning every detail. He didn’t want to charm—he wanted to make his mark. To engrave his name, and that of his film, in cinema history.

When it was released in 1941, critics praised the film’s ingenuity, but the public remained wary, influenced by Hearst’s smear campaign. Citizen Kane received nine Oscar nominations, but won only one—for Best Screenplay. Hollywood, annoyed by this overly self-assured young man, gradually turned its back on him. Welles entered a period of decline. He would never again enjoy such creative freedom.

But the story didn’t end there. In the 1950s, the film was rediscovered in Europe. In France, the critics at Cahiers du Cinéma—Truffaut, Godard, Rohmer—celebrated it as a revolution. By the 1960s, it steadily climbed to the top of lists ranking the greatest films in cinema history—a place it has held ever since.

Because Citizen Kane is a film that speaks to everything: power, wealth, loneliness, loss, and the childhood left behind along the way. The word “Rosebud,” the last trace of a vanished world, becomes a universal symbol. A simple object, loaded with memories, pain, and regret. What Kane valued most—and abandoned in his quest to own everything.

Welles put everything he had into this film: his passion, his intelligence, his ambition. He defied the powerful, broke conventions, and challenged even the language of cinema itself. He wanted to say everything—and came very close.

Citizen Kane is both a warning and a masterpiece. It is proof that cinema can think, provoke, and innovate—even from within the system. It is also the portrait of a man who understood too much, too soon.

Comments