In his writing workshop, Georges Perec draws inspiration from instruction manuals, spinning words like the drum of a washing machine. By delving into everyday life, he creates a literature where household items become sources of invention and poetry.

A drum, a muffled sound, cycles, programs. A round door swings open onto the world’s laundry. A washing machine, yes – but for Georges Perec, it’s never just an appliance. It’s a trigger – his engine for writing. In the workshop of this master of literary constraints, even the most ordinary object can become a source of invention. Especially the simplest ones.

You could imagine an opening line – very much in Perec’s style: “Front-loading washing machine, 5 kg capacity, 800 rpm spin cycle.” A technical sentence, perhaps, but one that could just as easily begin a novel or a poem. Perec used to say – half-joking – that the user manual was a form of literature. He turned it into a writing tool. Drawn to rules, lists and fixed forms, he saw household appliances as another way to set language in motion – like the drum of a machine.

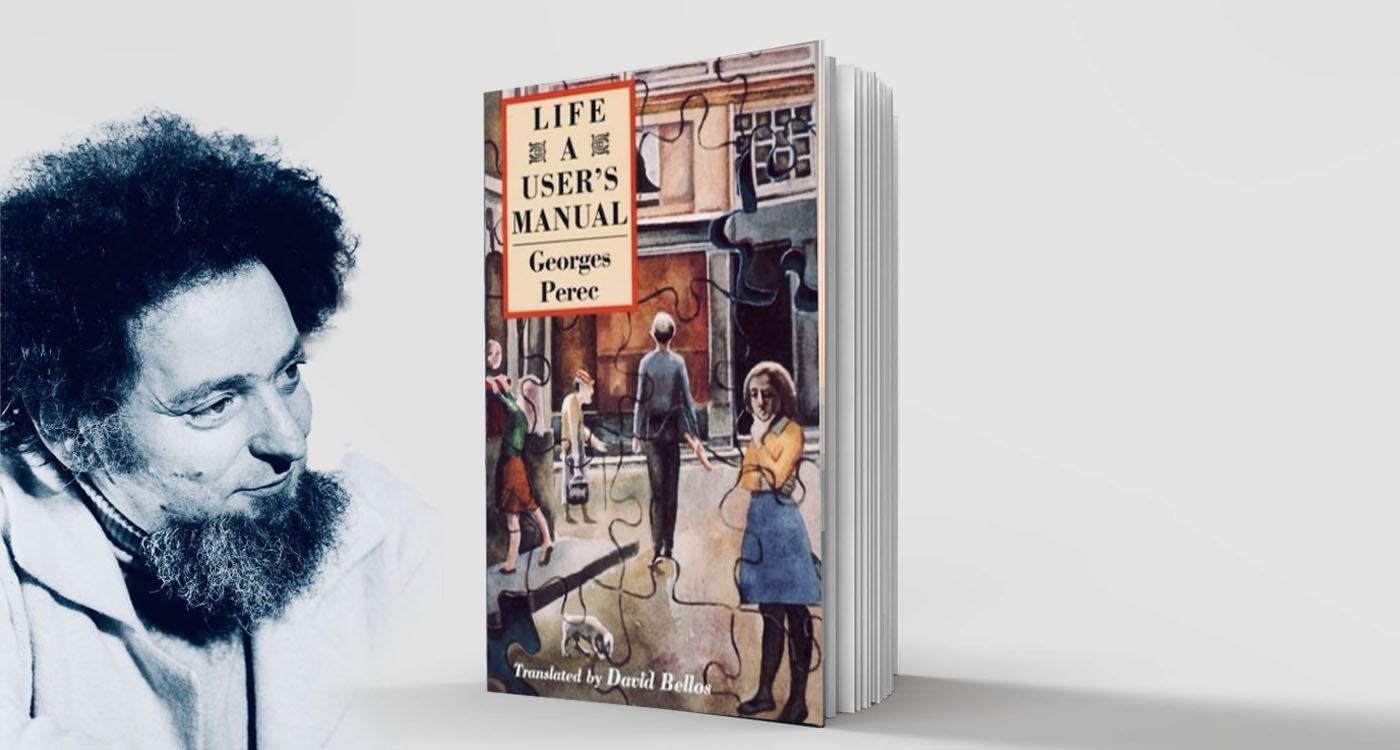

It’s no coincidence that the washing machine features in La Vie Mode d’Emploi (Life: A User’s Manual, 1978), one of Perec’s most ambitious works. The novel tells the story of a Paris apartment building, room by room, along with the lives of its residents. The machine turns up in a bathroom or a laundry room – quietly, but unmistakably present. More importantly, it echoes the structure of the book itself. The spin cycle puts language to the test. The pre-wash is a plunge into memory. Fabric softener adds a hint of poetry. Every button tells a story.

This fixation on everyday objects runs through other works of his – some even more experimental. In Un Homme Qui Dort (A Man Asleep, 1967), the narrator withdraws from the world, watching his life pass by without taking part in it. Everything becomes mechanical and repetitive. The fridge hums, the lamp shines on its own, the washing machine spins on a loop. These objects set the rhythm of a life drained of desire. They fill the space left by the absence of will. Household appliances become characters in their own right.

But it is in L’Infra-ordinaire (The Infra-ordinary, 1989), a collection published after his death, that Perec takes this idea the furthest. There, he questions our everyday lives: “What have we done with our days? With our gestures? With our objects?” The washing machine becomes a symbol of what we no longer see. Like so many household items, it blends into the background. Its constant presence makes it invisible. For Perec, writing means giving new weight to what we’ve stopped noticing.

This is the exact opposite of romanticism. Where others write about sweeping landscapes, fiery passions or mysteries, Perec focuses on the power outlet, the light switch, the user manual. It is in this attention to the ordinary that his strength lies. He turns the sink into a stage, dust into a subject, the washing machine into a literary object. His genius lies in writing about things no one else considers interesting.

For Perec, the washing machine is also a nod to his era: the “Trente Glorieuses,” when households began acquiring appliances and comfort became an attainable dream. It’s an object that eases chores. But it’s also a symbol of routine and repetition. Perec doesn’t judge. He observes – with tenderness, with humor. He seeks to understand what these objects reveal about us, our habits and our expectations.

At its core, what Perec really spins isn’t clothes – it’s language. He twists it, sends it through turns and cycles. His prose, like a garment fresh from the wash, is never perfectly pressed; it holds creases that tell a story.

And then there’s this somewhat wild but beautiful idea: that anything can become literature. A button, a hinge, a drum, a laundry drawer – anything. For Perec, no subject is insignificant. He constantly asked himself: why do we always write about the extraordinary? Why do we forget that life is made up of crumbs and dust? By choosing the washing machine, he’s really addressing our need to put things in order and start anew.

It’s no accident that in Perec’s work, actions often feel mechanical. He is like a watchmaker of language – each word a gear, every sentence triggering a chain of logic. Yet within this mechanism, there is always a flaw. Reading Perec is like stepping into a laundromat. You set your gaze, press “delay start,” take a seat, and wait. Eventually, something surfaces – a soft noise, like a drum spinning. A mix of memories and foam. Then you realize it’s not just a washing machine. It’s poetic prose. And Perec is at once the engineer, the repairman and the faithful customer.

Comments