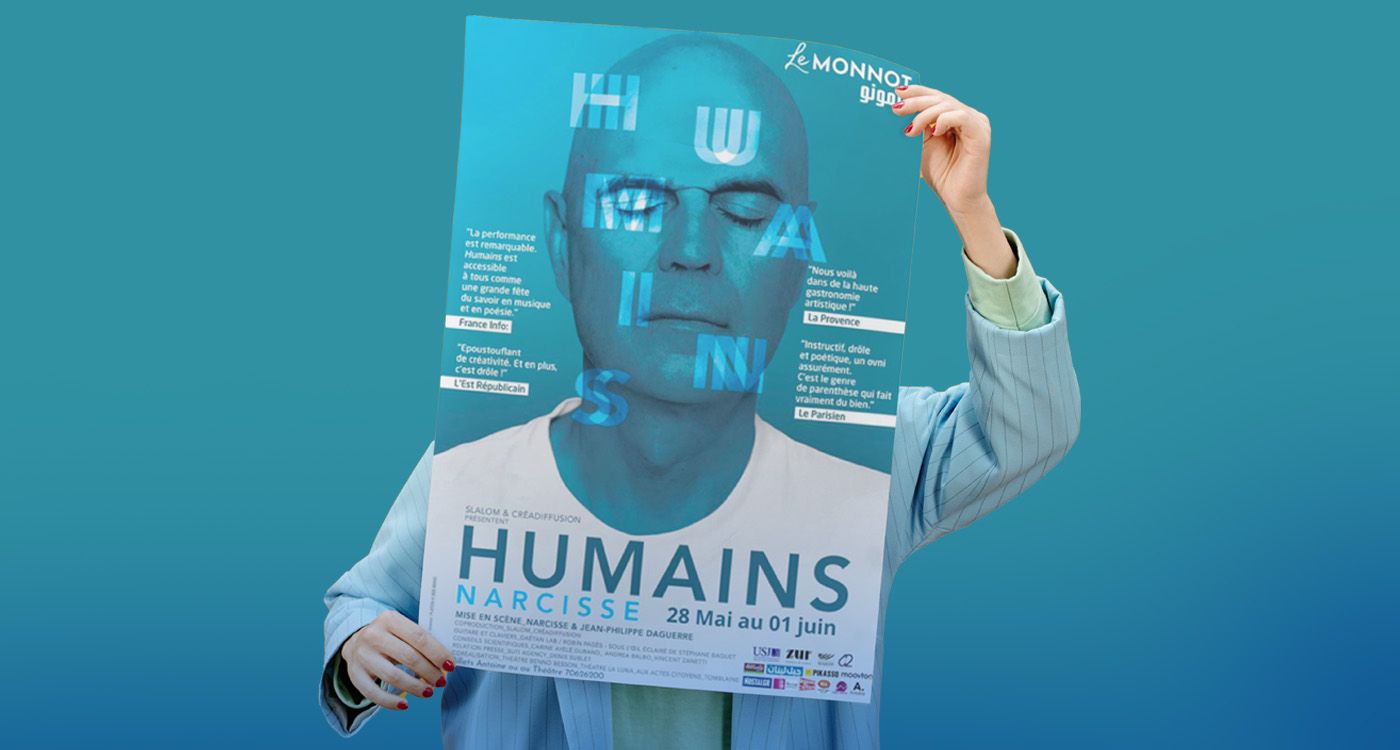

From May 28 to June 1, Le Monnot Theater will host Humans, a moving and artistic reflection on what it means to be human. Swiss artist Narcisse delivers a one-of-a-kind stage experience blending poetry, live music, and fresh perspectives on knowledge. The performance is at once intimate and universal, humorous and thought-provoking. An interview with Narcisse for This Is Beirut.

From May 28 to June 1, Le Monnot theater welcomes Humans, a unique performance by Swiss artist Narcisse. Directed by Jean-Philippe Daguerre, this poetic-musical creation explores human knowledge through an innovative staging that blends poetry, music, and theater. Praised by French critics, Humans stands out for its intellectual richness, boundless creativity, and subtle humor. Narcisse spoke with This Is Beirut about the play.

How does your piece reflect its title, and how did the idea come about?

During the Covid pandemic, I wrote a slam poem as a tribute to healthcare workers. The video of that poem went viral on social media, and I received messages from all over the world telling me how much it helped them. At the same time, there was a growing sentiment that humanity had lost its way, that we were somehow worth less than other animals. As a follow-up to my tribute, I wanted to help us reconnect with what makes us human—what we’re capable of. After all, we’re the only species that writes, paints, composes music, and has walked on the moon. I'm not saying everything is fine—far from it. And as a European man, I don’t pretend to speak for all of humanity. In fact, the show’s script was reviewed and enriched by several people, including the director of the Geneva Museum of Ethnography, a woman of African descent. I believe we need a better world—but we won’t get there if we only listen to people saying we never will.

What drew you to this project in particular?

What sets Humans apart, I believe, is our incredible ability to learn from each other and build upon collective knowledge. Think about it: alone on a desert island, no one could make a smartphone. That device is the result of thousands of years of shared invention and discovery. And that’s just one example. Humanity is made up of all of us, not just the famous names the media focuses on—like Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos. Humans is my attempt to tell that broader story. I speak from personal emotion, but also from research—I read about 50 books while creating this. I’m not here to lecture anyone on being human.

How did you manage to blend all the artistic disciplines so seamlessly?

In all my shows, I love working across multiple art forms. I imagine the final result from the beginning, and I develop text, music, video, and technology all in parallel. That’s probably why my shows feel cohesive. But the heart of it all is the text. Technology is always in service of the message.

Can we still speak of “humanity” in a world fractured by individualism? And how do technology and holograms fit in?

People often say we’ve lost our humanity. But let me share a story: near my home, a woman fainted in the street. Immediately, someone lifted her head, another ran for water, another called emergency services, and someone else held her hand and comforted her. This kind of response is completely normal—and would happen almost anywhere. I believe we are far more human than we give ourselves credit for. Sure, some people commit atrocities, and they dominate the headlines. But to make progress, we must stop thinking we're worthless.

As for technology—it’s just a tool. It can be used for good or harm: atomic energy can power bombs or cure cancer. In my show, holograms allow me to have 20 performers on stage at once, showing how music and dance from around the world can harmonize. It also adds a bit of magic. People often tell me they can’t tell who’s real and who’s a hologram—and I love that playful ambiguity.

Should we prioritize beauty over utility—or the other way around?

I’m not here to give advice. But in the show, I highlight how many discoveries were first used to create beauty before finding practical uses. For example, we made fireworks for 600 years before using gunpowder in cannons. And isn’t it wonderful that we can simply enjoy a sunset or a piece of music?

Do you think slam poetry belongs within the tradition of poetry?

Slam is poetry—plain and simple. It began in Chicago in the 1980s as a way for people to share poems out loud. Over time, it evolved: now slam artists set their words to music, make albums, and stage performances. Because of that, slam is often confused with a musical genre close to rap. But at its core, it’s still poetry—just one where people don’t fall asleep. And that speaks to me.

Tell us about working with Jean-Philippe Daguerre, especially after his 2025 Molière Award for Best Director.

I’ve known Jean-Philippe Daguerre for over ten years. We have great mutual respect, even though we come from different worlds: he’s rooted in classical theater, while I come from music and multimedia performance. I wanted Humans to be tied to the grand tradition of theater, so I asked Jean-Philippe if he’d direct it. He immediately said yes, even before reading the script.

He later wrote a short text about our collaboration that I found very moving: “When Narcisse honored me by asking to get involved with his new piece, I said yes before even reading it. And when he handed me Humans, I immediately knew I was holding a masterpiece. All I had to do was add my little touch to this extraordinary creation.” I’d add that one of Jean-Philippe’s many strengths is his humility. What he calls his “little touch” actually enriched the entire show.

Comments