Long before it became a glamorous showcase beneath the lights of the Croisette, the Cannes Film Festival emerged from a bold, forward-looking act of defiance: a refusal to let politics dictate the course of art. Behind today’s red carpets and awards lies a largely forgotten history, in which cinema defied dictatorship and became a tool of freedom on the eve of world war.

It was the late 1930s. The Venice Mostra, founded in 1932, was the world’s first international film festival. But by 1938, as global tensions mounted, it had turned into an ideological showcase for fascism. Under joint pressure from Hitler and Mussolini, the jury was compelled to award the festival’s top prize, the Mussolini Cup, to two propaganda films: Olympia, the Nazi documentary by Leni Riefenstahl, and Luciano Serra, Pilot, an Italian production personally endorsed by the dictator’s own son. The scandal caused outrage among delegates from several countries—including France, Britain and the United States—who chose to walk away from the Mostra in protest against the exploitation of art for political ends.

Upon returning from the Mostra, diplomat and historian Philippe Erlanger—then director of the French Association for Artistic Action—envisioned a competing festival, one free from political influence. His idea was clear and forceful: to offer cinema a neutral, independent platform where films would be evaluated on their artistic merit, not their ideological agenda. Erlanger presented his plan to Jean Zay, the young and dedicated Minister of National Education and Fine Arts, known for his strong republican principles. Backed by Albert Sarraut, then Minister of Interior, the project began to take shape, despite the political risks posed by strained relations with fascist Italy.

A Debut Cut Short by War

In May 1939, Cannes was officially selected to host the new festival. Other cities, including Biarritz, were strong contenders, but the sunny climate, hotels and strategic location of the French Riviera won over the committee. The project progressed rapidly, with the event scheduled for September, and Louis Lumière was named honorary president. Nine countries answered the call, and films like The Wizard of Oz and Union Pacific were included in the lineup. The movie world was on the verge of a defining moment.

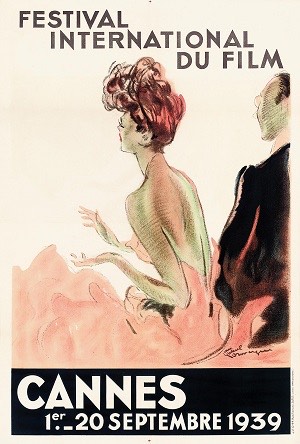

False start for the Cannes Festival in 1939. © DR

But history had other plans. On September 1, 1939—the very day the festival was set to open—Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, France and the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. The festival was cancelled before it even began. Only one film, The Hunchback of Notre Dame by William Dieterle, was screened amid a mood already darkened by the looming threat of war. Guests departed Cannes abruptly, and the hope for a major, independent cinema event was temporarily put on hold.

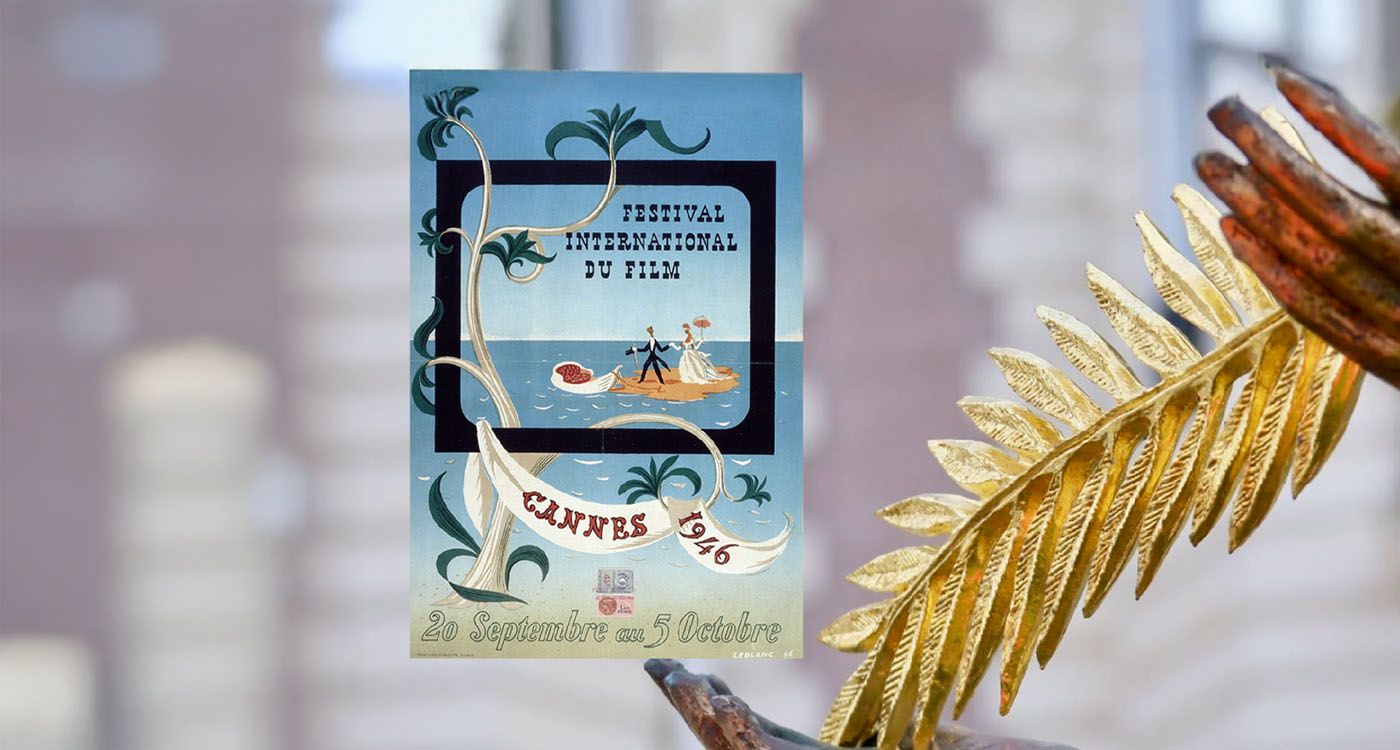

Not until 1946, in the aftermath of the Second World War, would the dream finally come to life. On September 20, under a radiant sun, the first official edition of the Cannes Film Festival opened amid an atmosphere of joy and renewal. Twenty-one countries were represented, including the United States, the USSR, France and the United Kingdom. Among the guests were Jean Renoir, David Lean and Walt Disney. According to some recollections, Philippe Erlanger is said to have described the event as “the world’s first celebration, in a kind of intoxication, beneath a sun that would shine steadily until mid-October.”

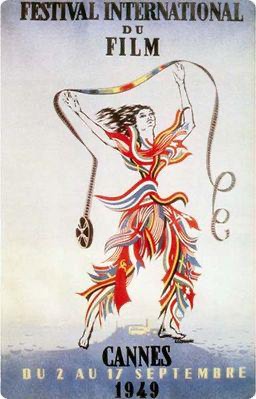

The poster of the Cannes Film Festival in 1949.© DR

The Cannes Film Festival was not born of mere cultural or touristic ambition, but of an act of resistance—resistance to censorship, to ideological control, to the subjugation of art by authoritarian regimes. It stands as a direct continuation of the determination to defend freedom of expression, even in the darkest of times. This spirit of resistance, often forgotten, gives the festival a historical depth that goes far beyond the glamour. With every walk up the steps, there is also a quiet tribute to those who, against all odds, insisted that cinema remain free.

Comments