A towering figure of Latin American literature and a literary citizen of France, Mario Vargas Llosa passed away in Lima at age 89. From Paris cafés to the French Academy, his journey bridged two continents through the power of storytelling.

Born in 1936 in Arequipa, Peru, Vargas Llosa left his homeland in the 1950s, believing that true literary ambition could only flourish elsewhere. He arrived in Paris in 1959 at the age of 23 with his first wife, Julia Urquidi, who would later inspire Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter. He found a city pulsing with intellectual energy—where Sartre and Camus debated ideas, and where Latin American authors like Octavio Paz were already widely read.

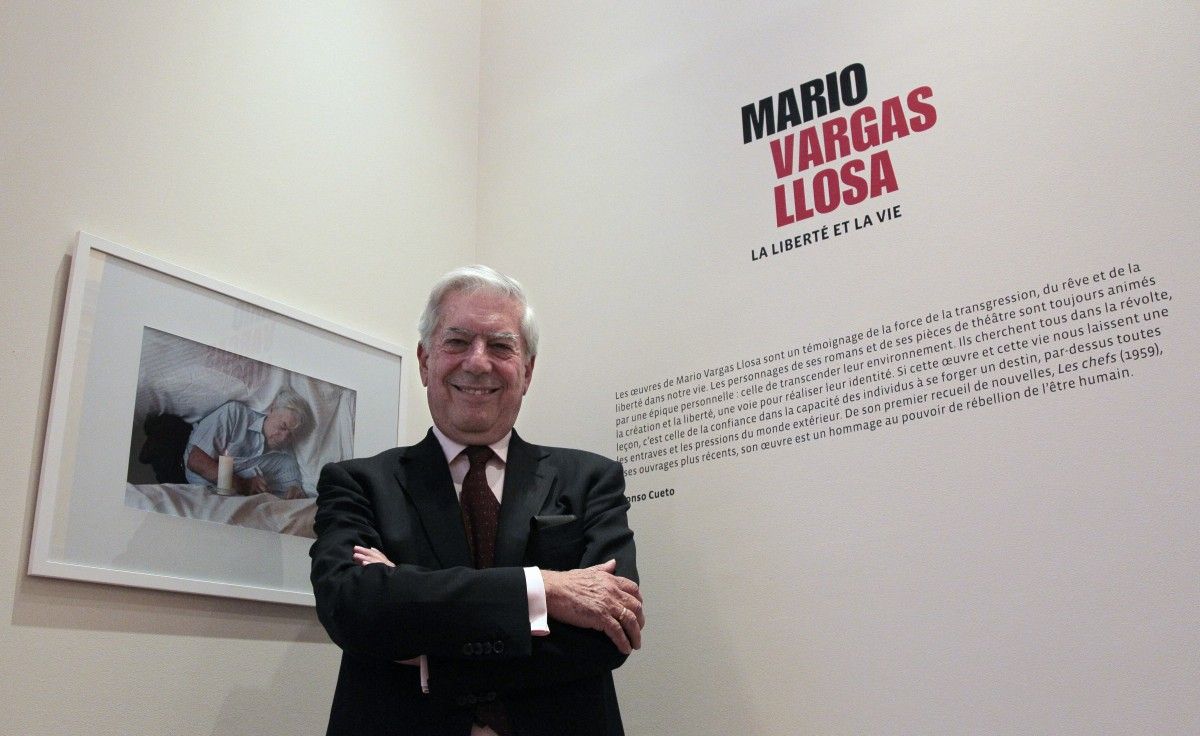

A Writer Born in Paris

Mario Vargas Llosa died in Lima, the city of his final years, but it was Paris that shaped his literary soul. “I became a writer in France,” he declared in February 2023 during his induction speech at the Académie Française—a rare honor for someone who never wrote directly in French.

Flaubert’s Heir in the Latin World

Shortly after arriving in France, he purchased Madame Bovary, the novel that would become his lifelong literary compass. The influence of Gustave Flaubert led to his critical essay The Perpetual Orgy, a deep exploration of what it means to be a writer.

Alongside Flaubert, Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas shaped his narrative sense. In 2004, Vargas Llosa published The Temptation of the Impossible, a brilliant meditation on Hugo’s Les Misérables, where he explored the tension between political ideals and fictional form.

His admiration for French literature was later crowned by two unprecedented honors: in 2016, he became the first living foreign author to be published in the prestigious Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, and in 2021, he was elected to the Académie Française.

From El Desafío to Literary Triumph

Long before global recognition, Vargas Llosa’s literary connection to France began in 1957 when he won his first prize for the short story El Desafío (The Challenge), awarded by La Revue Française. At the time, he was convinced that becoming a writer in Peru was impossible—“a country with no publishing houses and very few bookstores,” he would later recall.

Paris gave him the space to work. He taught Spanish, translated, and worked as a journalist at Agence France-Presse. And he began writing his first novel, The Time of the Hero (La ciudad y los perros), a powerful indictment of military brutality in Peru. The novel won the Biblioteca Breve Prize in 1962 and launched his international career.

Voice of the Latin American Boom

Alongside Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortázar, Juan Rulfo, and Carlos Fuentes, Vargas Llosa became a pillar of the Latin American literary "boom" of the 1960s and ’70s. Unlike his peers, he resisted the pull of formal experimentation and remained faithful to classical storytelling—favoring structure, conflict, and clarity.

His novels tackled corruption, authoritarianism, sexuality, and identity with unflinching honesty. Conversation in the Cathedral, The War of the End of the World, and The Feast of the Goat solidified his reputation as a master of political fiction and psychological depth.

A Sharp Political Shift

In the early 1970s, Vargas Llosa distanced himself from Cuban communism and gravitated toward liberalism, influenced by French political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville. This ideological shift earned him criticism from South American intellectuals but brought him closer to thinkers like Jean-François Revel in France, who welcomed his anti-totalitarian stance.

He would go on to become a vocal critic of authoritarian regimes across Latin America, engaging in public debates and even running for president in Peru in 1990—an experience that would later feed his novels.

Rediscovered by a New Generation

Vargas Llosa’s influence continues long after his Nobel Prize win in 2010. Streaming platforms like Netflix and Prime Video have sparked a renewed interest in Latin American classics, adapting major works of the “boom” generation for global audiences.

His 2006 novel The Bad Girl is set for adaptation, as are García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and Isabel Allende’s The House of the Spirits. “It’s not just about their era,” says Netflix VP Francisco Ramos, “these are simply great stories.”

According to a 2024 report by Digital TV Research, Latin America is set to see a 50% increase in streaming subscribers by 2029—up to 165 million households. Platforms are racing to meet the demand with quality content that resonates both locally and globally.

A Final Stroll Through Lima

In late March 2025, just days before his 89th birthday, Vargas Llosa reappeared in public in a series of photos shared by his son Álvaro on social media. The images showed the author walking through Lima—his city of memory and fiction—where he had written his last two novels: Cinco Esquinas (2016) and I Dedicate My Silence (2023).

In one photo, he walks arm-in-arm with his grandson Leandro, dressed simply in a light shirt, dark trousers, and sneakers. It was a quiet, intimate image of a man who had lived through literary revolutions and ideological storms, now returning to the streets that first inspired him.

Between Two Worlds

In his 2010 Nobel Prize speech, Vargas Llosa said: “I have never felt like a foreigner in Europe—or anywhere else.” It was a statement that defined his entire life: born in Peru, reborn in France, and recognized everywhere as one of the finest novelists of his generation.

Through language, he built bridges between worlds. And it was in France—his adopted literary homeland—that Mario Vargas Llosa truly became the writer he had dreamed of being.

Comments