Lebanon is preparing to overhaul its school curricula, including the history program, which remains in the drafting stage. While the details of the future curriculum are still confidential, one central question looms: Could history one day be taught in Lebanese schools through multiple perspectives—in a country still deeply divided over its past?

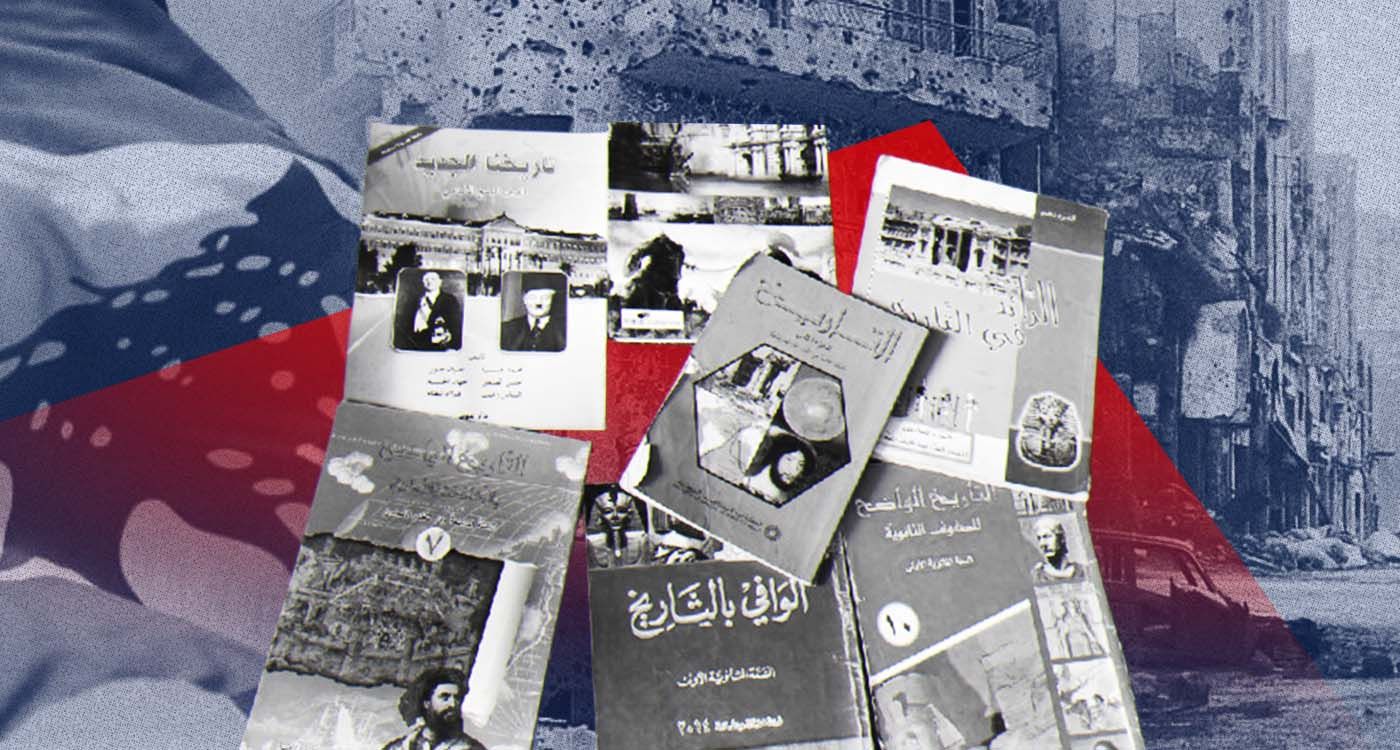

In Lebanon, the official history textbook ends with the withdrawal of French troops in 1946, following the country’s independence in 1943. Entire chapters of the country’s modern history remain unaddressed—most notably the 1975–1990 war, which left at least 150,000 dead and 17,000 missing. Even the terminology remains contested: Should it be referred to as “the events” (al-ahdess)? A civil war? A regional conflict? A proxy war?

In 2022, the Center for Educational Research and Development (CERD), under the supervision of the Ministry of Education, relaunched a plan to overhaul the curriculum. “We are currently in the drafting phase,” CERD president Hiyam Ishak told This is Beirut. According to the official timeline, the new programs are expected to be introduced in schools by 2026.

What direction might the new history curriculum take — and is a single, unified narrative a necessary starting point for a new textbook?

Teaching About War to Build Peace

On January 25, 2007, history teacher Lamia Hitti was watching TV when scenes of armed clashes between young men outside a university flashed across the screen. The moment has stayed with her ever since.

“One thought kept coming back: maybe if we taught the history of the war, we could build peace.”

“We’ve clearly fallen short in education,” she told This is Beirut. “We’re carrying the wounds of the war and handing them down to younger generations—yet we’ve done almost nothing to help them understand how to move past the trauma.”

Drawing on her experience as an educator, Hitti observes that while many Lebanese students are eager to learn about history, they are often exposed to only fragments of it.

“What is needed is an academic framework for teaching sensitive history,” she explains. “In such cases, we can draw on multiperspectivity—a pedagogical and historiographical approach rooted in Western education—which can equip students with tools for critical thinking.” This approach, she adds, would offer significant educational value, fostering empathy and encouraging respect for different narratives.

For instance, take April 13, 1975, commemorated as the day the Lebanese Civil War began, also linked to the massacre of the Ain el-Remmaneh bus.

“There isn’t just one narrative of what happened that day; there are numerous perspectives. So, we will encourage young people to conduct a historical inquiry, drawing insights from document analysis,” explains Hitti. These documents could include testimonies, writings by historians or even excerpts from novels, film sequences or songs.

What really happened on April 13? The answer isn’t straightforward, as there are still unresolved and murky aspects. “We must accept that there are still open questions,” says the teacher.

Historians are often criticized for their inability to agree on a single version of events. “The historian is not a judge, and the history curriculum is not a courtroom,” she asserts.

Beyond the accounts of massacres and battles, the human experience remains the same on both sides of the so-called demarcation line. “This is also what needs to be emphasized: the stories of people who advocated for peace, even during war, and those who helped each other despite holding opposing political views,” Hitti added.

A Necessary and Thorough Preparation

To implement a multiperspective approach in history education, it is essential to remain vigilant in order to avoid “the risk of falling into a war of memories,” according to the educator.

The classroom should serve as “a safe space where historical narratives meet personal stories, within a framework of mutual respect,” she stresses. This environment would be guided by the teacher, who must first receive specialized training. “They must learn to manage their own emotions and memories in order to create space for the students and strike a balance between memory and history,” she adds.

Simultaneously, “proper societal preparation is essential, as the process of reconciliation must start at the grassroots level, not be confined to political institutions,” Hitti explains. In this process, the media plays a crucial role, as do micro-communities. Individual initiatives and social activities, especially at the municipal level, contribute to rebuilding the puzzle of collective memory, she notes.

However, this momentum would be insufficient without “a political will capable of uniting these efforts under an institutional framework,” she warns.

Deferred Reforms: A Curriculum in Perpetual Limbo

The first curriculum established after Lebanon’s independence was created in 1946. It was revised in 1968, 1970 and 1971. A reform initiative was launched in 1994, resulting in new curricula in 1997-1998, followed by evaluation guides in 2000.

“The gap between reforms is about 25 years, whereas the legal requirement is to renew the curriculum every three years, as stated in the 1997 decree,” explains Ishak.

The Taif Agreement (October 22, 1989), which marked the end of the war that began in 1975, assigned the state the responsibility of revising school curricula. According to this document, the restructuring of curricula aims to “strengthen national belonging and integration, as well as spiritual and cultural openness.” The Lebanese state is expected to carry out, in this spirit, “the unification of textbooks in the subjects of history and national education” (Part I, Art. 3.E, Paragraph 5).

Subsequent reform initiatives were launched, but ultimately not completed. The efforts included a competency-based curriculum in 2008 and preparatory meetings from 2016 to 2020, the outcomes of which were not incorporated into the official curriculum.

Between 1996 and 2000, two commissions— for Civic Education and History—were tasked with updating the curriculum. The resulting 90-page work was published in the Official Gazette, following a ministerial decree unanimously approved by the Council of Ministers, with support from all educational institutions (Decree No. 3175, June 8, 2000, Official Gazette No. 27, 06/22/2000, pp. 2114-2195). However, after being printed, the textbooks were withdrawn from circulation for political reasons.

An Ongoing Initiative

The current action plan for renewing school curricula was launched in 2016, though it has experienced several interruptions.

“The reform project was relaunched in 2022,” explains Ishak. “The CRDP formed committees, enlisting both Lebanese and French experts, particularly in history and civic education.”

Following the development of a national curriculum framework that defines core principles, 11 educational policies were introduced. A pilot phase was then carried out to test and assess these policies in a controlled environment.

Currently, the curricula for each subject are under development. This phase will be followed by the creation of textbooks and digital resources, leading to their implementation in schools.

The details of the new curriculum, particularly for history, remain confidential for the time being. What changes can we expect?

At the same time, some history teachers are already adopting innovative methods that have proven effective in the field of education.

In 2019, hundreds of students gathered in front of the Ministry of Education to protest an “outdated” history textbook, symbolically burning a copy in protest.

Will the long-awaited new official curriculum live up to the expectations of the entire Lebanese population?

The Center for Educational Research and Development (CRDP) was established in 1971 under the Ministry of Education and Higher Education's supervision. This public institution is responsible for overseeing educational projects in the school system. It defines curricula, manages official exams and conducts various educational research, publishing periodic bulletins for this purpose. Additionally, it is tasked with training teachers in the public school sector.

Comments