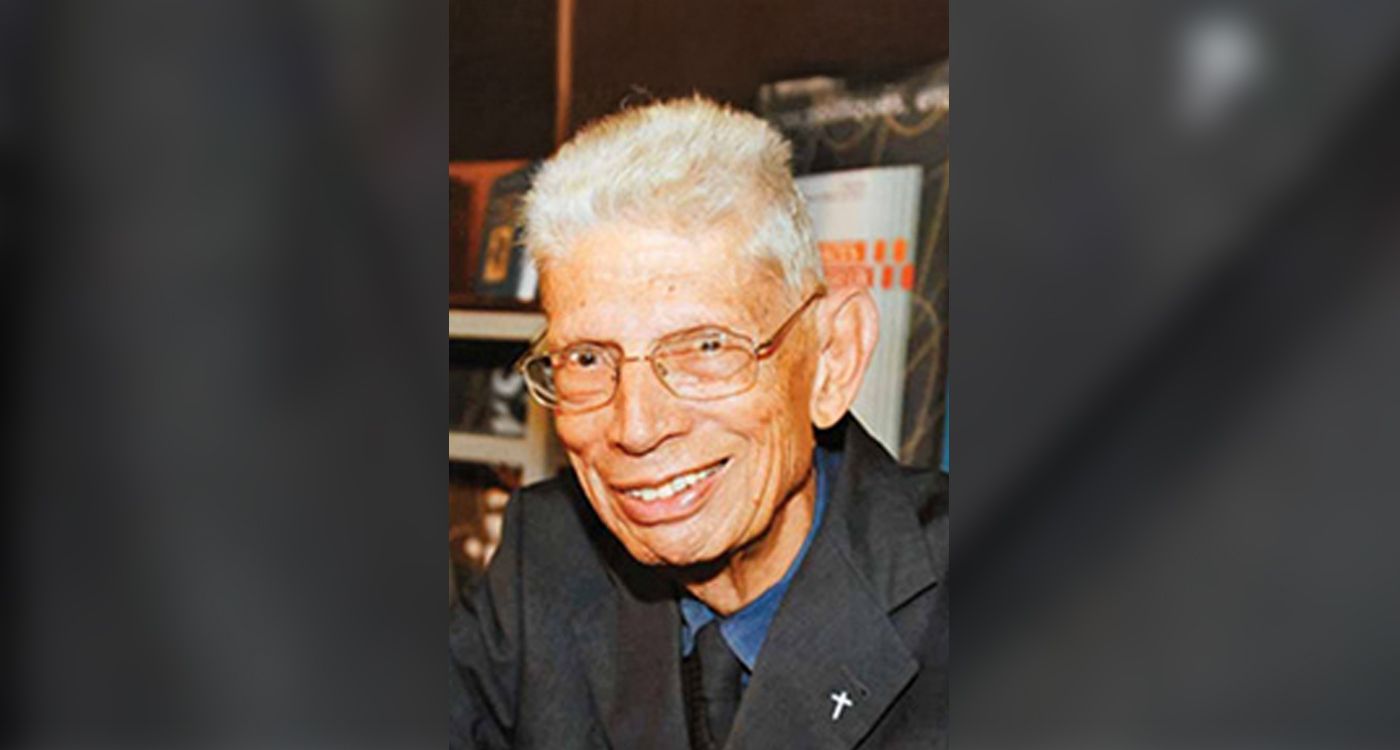

The chaplaincy of Saint Joseph University (USJ) had the inspired idea this year to honor Father Jean Ducruet (1922–2010), rector of USJ from 1975 to 1995, by dedicating its 8th Jesuit Week (March 10–14) to him. This tribute coincided with the 150th anniversary of the university’s founding in 1875.

To rediscover Father Jean Ducruet, one need only turn to L’Université et la Cité, a meticulously curated collection of his texts compiled by the university. This work highlights the breadth, diversity, and depth of his knowledge, the incisiveness of his reflections, and the unwavering determination with which he steered an institution that, without his leadership, might have faltered—but which he instead transformed into a leading private Lebanese university.

Indeed, in 1972, the Society of Jesus had contemplated closing the university altogether.

The book compiles speech transcripts spanning twenty years of his rectorship. From this extraordinary compilation emerges a man whose foreword highlights one of his greatest qualities: dedication.

This virtue is beautifully illustrated in a quote from General de Gaulle. Speaking in 1931 at Saint Joseph University’s College in Beirut, de Gaulle—then only a commander—stated:

“For collective tasks, energy and aptitude are not enough. Dedication is a must. One should be willing to sacrifice something of oneself for the common goal.”

This quote offers a glimpse of Father Jean Ducruet—a man of vision, endurance, and self-sacrifice.

The phrase "speech transcripts" may seem misleading. There is no banality in these texts, no matter how simple or circumstantial their occasion. Readers quickly realize that the rector fully embraces the weight of his office and always transcends the moment to address essential concerns. The book exemplifies this approach as every text carries the dual concern of learning and cultural and spiritual education; and every technical discussion connects back to the human and social dimensions of education.

"Resignation Is Not Lebanese"

No detail escaped Father Ducruet’s keen awareness. One striking example is his discourse on the importance of dialogue between doctors and nurses:

“How can a medical team remain motivated if they believe, rightly or wrongly, that the procedures they are asked to perform amount to therapeutic obstinacy?”

This remark, from a speech on the nursing profession, reflects the impact of Lebanon’s wartime struggles. Addressing a graduating class of nurses, he urged them “never to give up”—whether to poorly executed work or to the partitioning of their homeland.

“Do not give up,” he insisted, “because, through your profession, you will witness the suffering of the wounded, the rebellion of the maimed, the despair of families, and the misery of the poor.”

And he solemnly concluded: “Resignation is not Lebanese.”

Father Ducruet carried this patriotic message to all campuses—whether addressing students in humanities, law, economics, management, medicine, or engineering.

On Saint Joseph’s Day (March 19), his speeches took on a pedagogical tone. He analyzed the social realities of war, the conditions needed to restore social bonds, and the actions required to make the rule of law more than just an abstract concept—transforming it into “the historical horizon of fragmented narratives.” His speeches indeed serve as roadmaps for rebuilding the nation.

"Allowing Freedom to Emerge"

At the heart of his philosophy, citing Paul Ricoeur, he defined the mission of a worthy university education: “To a great extent, it consists of inscribing each individual’s project of freedom within a shared history of values.”

To this illuminating definition, he added: “Helping someone in their education means, first and foremost, helping them bring their freedom to life within the constraints that shape them.” (March 18, 1995, Patronal Feast of the University).

How far removed this vision is from the diploma factories into which so many institutions have degenerated!

In a Middle East shaken by fundamentalism and violent upheavals, Father Ducruet patiently cultivated in his students a sense of history and hope, making them aware that they were part of a nation in the making.

This Christian sense of hope—as a driving force of history—shone through in a graduation address at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities (January 8, 1994).

Speaking at a university inspired by Christian values (though never doctrinally rigid), Father Ducruet reflected on Lebanon’s rich multilingual literary scene, saying:

“Observing the thousands of books in diverse languages at these exhibitions, I thought of great rivers that, near their mouths, split into sluggish streams… I felt compelled to turn from these sometimes polluted waters and journey upstream to the source—the water that springs from the rock.”

Abraham, the Common Ancestor

He then made a profound observation: “These sources of our literature and civilization—need they even be named? They are Greek literature, which unveiled the universal human, and Biblical literature, which—before Christianity and Islam—revealed God within human history.”

He concluded: “This new understanding of history, both personal and collective—how can we not see it embodied in the figure whom Jews, Christians, and Muslims revere as their common ancestor: Abraham, father of all wandering peoples?

He believed in God’s promise, foreseeing a reality not yet visible. He awakened humanity to history—the history of a promise fulfilled.

And with him, responding to the call of the migrant God, a God who is both on the road and the road itself, we became nomads. From then on, our existence, now carrying the promise of the future, became history.”

There is no doubt that L’Université et la Cité is a goldmine of reflections, a majestic portrait of a university captured through the words of a man who remains, thanks to this legacy, one of its pillars.

USJ: Guardian of Collective Consciousness

As Pope John Paul II once affirmed: “Born in Europe within the Church, the university institution is one of humanity’s masterpieces.”

Citing the venerable universities of Bologna, Paris, Oxford, Krakow, Salamanca, and Coimbra, he noted how they played an essential role in shaping European culture.

No less esteemed than its predecessors, Saint Joseph University belongs to this same lineage of institutions. Without it, Lebanon would not be what it is today.

For many, USJ has had the immense privilege of nurturing Lebanon’s collective consciousness—shaping awareness of national identity and freedom.

In tribute to his legacy, Beirut’s municipality named a modest street near the USJ rectorate after Father Ducruet, running alongside the rectorate from Damascus Street to the Lycée.

Yet this gesture falls short.

For so great an educator, there should be a grand square—a crossroads worthy of his name.

Comments