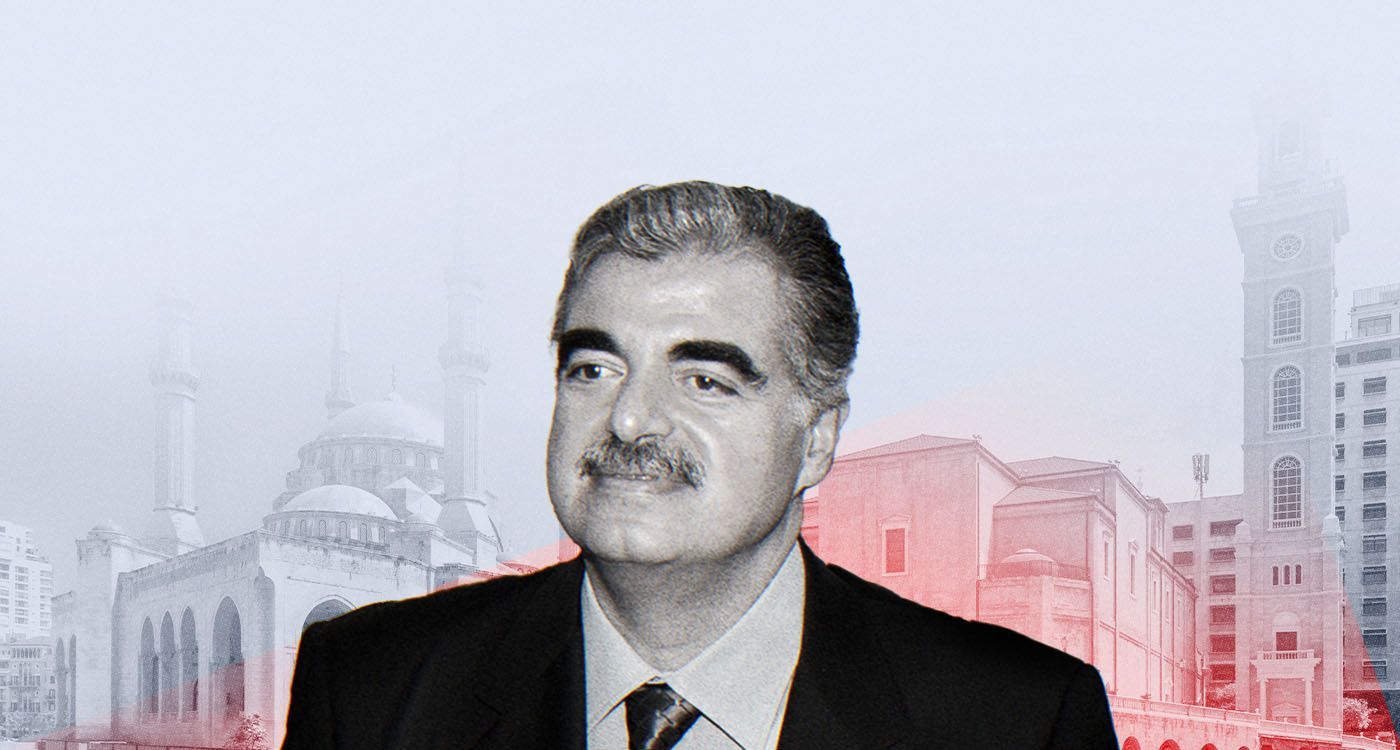

“No one can be greater than their country,” Rafic Hariri once remarked. Yet, two dominant forces in Lebanon challenged this notion: Hariri himself and Hezbollah. Their conflicting vision led to a violent confrontation—an all-out clash of titans—one that reached its climax 20 years ago, on February 14, 2005, when the former Prime Minister was assassinated along with nearly two dozen others. The Special Tribunal for Lebanon, based in The Hague, later implicated senior Hezbollah operatives in the attack.

Hariri had built a Sunni leadership that transcended Lebanon’s borders, earning him international recognition and influence. This growing stature was perceived as a fundamental “threat” by Hezbollah, a party unwaveringly committed to its transnational agenda and deeply entrenched in Tehran’s regional strategy.

Rafic Hariri’s ascent began in the wake of the 1982 Israeli invasion, when his company, Oger Liban—a subsidiary of Saudi Oger—undertook, at its own expense, clearing operations in downtown Beirut, a district left in ruins by years of conflict. This endeavor later evolved into large-scale reconstruction projects, reshaping the heart of the capital.

At the same time, during the 1980s, Rafic Hariri granted scholarships to more than 32,000 young Lebanese from across sectarian lines, enabling them to pursue higher education in Lebanon and abroad. This initiative not only cemented his influence but also strengthened his grassroots support, paving the way for his emergence as a dominant political figure.

A businessman and entrepreneur who amassed considerable wealth, particularly in Saudi Arabia, Rafic Hariri distinguished himself by making substantial investments, over many years, in projects that served the public interest—setting him apart from others. His efforts enabled him to establish himself as the undisputed and charismatic leader of Lebanon’s Sunni community, all while avoiding any sectarian approach.

His leadership spanned the country, from far north to the south, encompassing the Bekaa, Beirut and parts of Mount Lebanon. In doing so, he effectively laid the foundations of what could be termed “political Sunnism” while fostering dialogue with other communities—an approach that reinforced his reputation as a national leader with broad appeal.

Appointed to head the government in the early 1990s, Rafic Hariri left a distinct mark on the executive branch by spearheading ambitious infrastructure projects. A seasoned businessman with a deep understanding of private sector practices, he had a national vision and was not bogged down by restrictive or unproductive procedures. What set him apart was his ability to take risks, showcasing creativity, innovation and enough boldness to secure financing and execute large-scale projects, such as the airport that bears his name. It is notable that, since his death 20 years ago, no comparable large-scale infrastructure projects have been launched in the country.

Yet, Rafic Hariri’s influence extended far beyond Lebanon’s borders. He quickly gained international recognition, forging close ties with global leaders. He became the first Muslim leader in Lebanon to establish a privileged relationship with France at a time when Christian leaders were being sidelined by the Syrian occupier. Those who recall that period will remember his strong bond with President Jacques Chirac, whose unwavering political and economic support for Lebanon never faltered.

Rafic Hariri’s greatest vulnerability was arguably his close ties with both the Christian opposition to Syrian rule and key Sunni figures within the Syrian regime. The Pax Syriana imposed in the early 1990s, following the Taif Agreement, was built on a distinctly Baathist framework: all political and security matters remained the exclusive domain of the Assad regime and its Lebanese proxies, while Hariri was granted wide latitude over economic policy and development.

When the Future Movement leader made a concerted effort to engage with the Christian opposition around 2000-2001, the Lebanese-Syrian apparatus swiftly retaliated. In August 2001, mass arrests targeted student activists from Christian parties. “Rafic Hariri was supposed to stay out of politics and focus solely on economic affairs. Yet not only is he engaging in political action, but—worse still—he is forging ties with the Christian camp,” a pro-Syrian minister privately admitted at the time. (Ironically, that same minister would later switch allegiances…)

This was likely the turning point in the gradual breakdown in relations between Rafic Hariri and the Assad regime—one that would escalate until it became irreparable. The crux of the conflict lay in Hariri’s close ties with the Sunni wing of the Syrian power structure. His transnational Sunni network, which included key Baathist figures such as Abdel Halim Khaddam, Hekmat Shehabi and Ghazi Kanaan, was perceived as a direct challenge—both by the Assad regime and Hezbollah.

The devastating assassination on February 14, 2005, was followed by the systematic removal of prominent Sunni figures from the Baathist regime. Simultaneously, Hezbollah expanded its hold over Lebanese politics, while the Future Movement was progressively pushed to the margins.

Today, the regional dynamics have undergone a profound shift. Syria is no longer the same, with the downfall and fleeing of Bashar al-Assad, coupled with the significant weakening of the power held by the mullahs in Tehran and their regional proxy, Hezbollah. In light of the recent upheavals, could the 20th anniversary of Rafic Hariri's assassination mark a potential revival of what some describe as “political Harirism?” The answer is likely to unfold soon.

Comments