In January 2025, a devastating fire ravaged the Schoenberg family home in Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles, reducing thousands of Arnold Schoenberg's scores to ashes. Through an in-depth analysis and an exclusive interview with Larry Schoenberg, the composer's son, this article explores the musical legacy of this revolutionary figure and the impact of this loss on the transmission of his work.

January 2025. The scene seemed unreal. A devastating fire ravaged the Pacific Palisades neighborhood in Los Angeles, sweeping away everything in its path, including a major pillar of musical history. In the Schoenberg family home, Belmont Music Publishing preserved one of the greatest treasures of modern Western art music: the scores of Arnold Schoenberg (Vienna, 1874 – Los Angeles, 1951). The Austrian composer, who became a naturalized American citizen in 1933, is one of the most influential figures in 20th-century music, particularly for his foundational role in the development of atonal music and the twelve-tone technique, a method of composition based on the use of a series of twelve distinct pitches, without traditional tonal hierarchy.

The Schoenberg home, a true center of the composer's musical legacy, burned down in a matter of hours. Over 100,000 scores, which had supported the practice of orchestras and musicians around the world, were reduced to ashes. While the original manuscripts of the works were preserved, it was still a catastrophe for the living transmission of his music. These scores, borrowed and shared by orchestras of all sizes, were essential for interpreting his avant-garde compositions. “Arnold Schoenberg’s manuscripts were not affected by the fire disaster. His estate has been preserved at the Schönberg Center in Vienna since 1998. In 2024, the center in Vienna also received his paintings and drawings as a donation from the Schoenberg family,” said one of the officials from the Vienna department in an interview with This is Beirut.

For many musicians, these scores were the gateway to a sound that, before Schoenberg, was inaccessible. Leon Botstein, the conductor of the American Symphony Orchestra, immediately responded by calling these scores an “indispensable resource.” So who is this (misunderstood) revolutionist of the 20th century?

Musical Schism

Arnold Schoenberg was a composer and theorist whose radical approach to music upended the established norms of his time and now, ours as well. Throughout his career, he challenged the tonal system and classical harmony, primarily developed by Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) and Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), which had dominated Western art music for two centuries. Rather than following a linear evolution of tonality, he chose to break free from it, laying the foundations for atonality and thus founding the Second Viennese School. This approach led to a sharp break from long-established conventions. A schism, quite literally. He is to music what Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) is to visual art. “His legacy has been established,” said Lawrence Adam (Larry) Schoenberg, the composer's son, in an exclusive interview with This is Beirut. “In the long term, his innovation, determination and perseverance in following what he believed was necessary for what he would have considered progress in the evolution of music. His influence through his compositions and his writings are evident in the whole spectrum of music from popular, jazz through classical.”

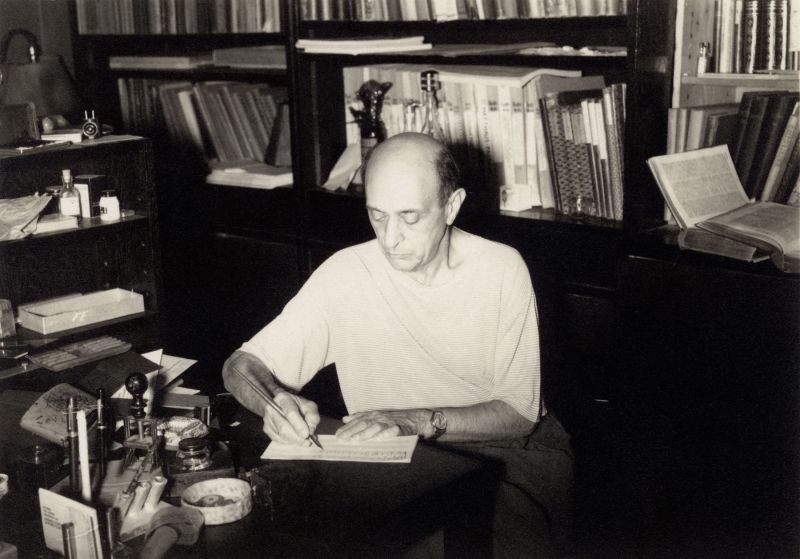

Arnold Schoenberg composing in his Los Angeles studio in 1940 © Arnold Scheonberg Center, Vienna

Stylistic Transition

His work exists within a historical context of stylistic transition, marked by the shift from late Romanticism to a completely avant-garde musical aesthetic. Schoenberg began his career within the tonal tradition, but very early on, he developed an increasingly experimental approach. Traces of the influence of Richard Wagner (1813-1883) and Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) can still be found in his early compositions, such as Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night, 1899). But he also introduced elements of dissonance that marked a turning point in his musical thinking. At the beginning of the 20th century, he abandoned tonality and experimented with atonality, a system that has no defined tonal center and where classical harmonic rules are systematically challenged. Schoenberg's true revolution came with the development of the twelve-tone technique, a method in which twelve notes are treated as equals. This contrasts with tonal music, which is based on chords and harmonies centered around a fundamental note, the tonic.

“When he encountered a problem, he identified it and then continued until he found, discovered or invented a solution,” explained Larry Schoenberg, who just celebrated his 84th birthday. “This could be applied to his bookbinding techniques, his solution for a four-way vehicle intersection, his automatic plant-watering device, as well as to our everyday lives, like how he prepared food for his children. Of course, that's exactly how he developed his twelve-tone composition, with each tone linked to the others.” This method allowed music to free itself from tonality while maintaining a certain formal and structural coherence. His Suite for Piano, Op. 25 (1921-1923), a set of five piano pieces, was the composer's first entirely twelve-tone work.

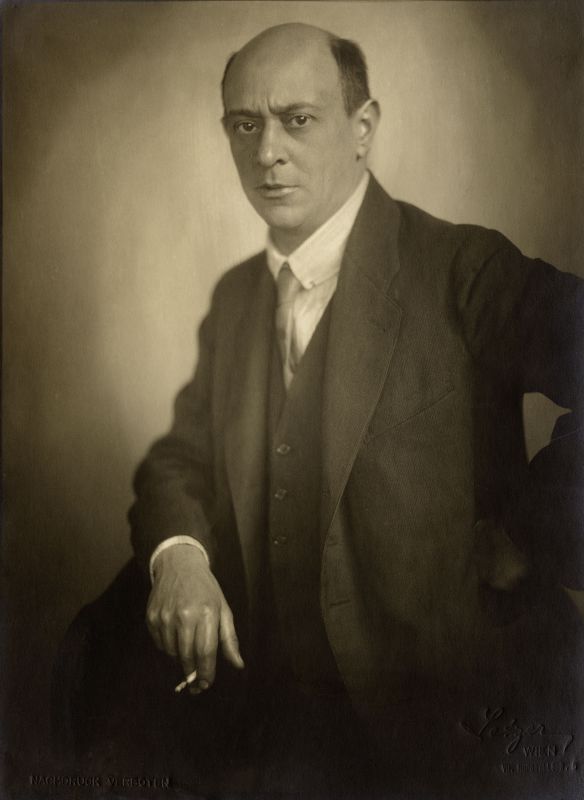

Arnold Schoenberg in 1922. ©️ Arnold Schoenberg Center, Vienna

‘Degenerate Music’

In addition to his career as a composer, Schoenberg was also a prolific theorist, having a profound influence on the evolution of modern music, both through his compositions and writings. In his Harmonielehre (Treatise on Harmony, 1911), he developed innovative ideas about harmony and musical organization, which would become essential principles in 20th-century musical thought. His move to the United States, following the rise of Nazism, marked an important turning point in his career. He continued to develop his musical ideas while also teaching and mentoring young composers, including notable figures such as John Cage (1912-1992). Schoenberg's influence remains crucial in 20th-century composition schools, despite the diversity of approaches that emerged after him, from minimalism to serial music.

During the Third Reich, Schoenberg's music was labeled “degenerate music” (Entartete Musik in German). The Nazis, with their very conservative and nationalist view of culture, rejected modern musical forms, which they considered foreign, decadent or even subversive. The term “degenerate music” was used by the Hitler regime to describe music they saw as deviating from classical and traditional norms. This view still lingers today, as many musicologists, critics and composers see atonality as a form of suicide of Western art. They explain that this “inevitable evolution,” which accelerated from the late 19th century, did not necessarily have to result in such breaks.

But what does Schoenberg's proud heir think? “As the famous Austrian philosopher Gustav Schneider would say, ‘Different opinions vary.’ Some people love Donald Trump, others not so much. I think that he would either have ignored it or more likely responded very strongly, with a comprehensive explanation based on his concept of the evolution of music,” he responds courteously.

Arnold Schoenberg with his friend and mentor Alexander Zemlinsky in Prague in 1917.©️ Arnold Schoenberg Center, Vienna

Difficult Times

Visibly upset, the octogenarian expresses his emotions regarding the tragic event caused by the devastating fire that destroyed his home. Calling the ordeal “difficult times,” he emphasizes that “the loss of the materials at Belmont Music and the personal loss of my home will in no way alter the way that my father's works will be performed.” His son, Arnie Schoenberg, stated to This is Beirut, “We were all very positive at first, but I think the shock is starting to sink in more and more.” Belmont Music Publishing, a publishing house dedicated to the works of the Austrian composer, had digitized much of its catalog. But some digital copies, stored only on local computers, were lost in the fire. “This now requires new digitization. We are rebuilding Belmont as a mostly digital publisher, but hope to provide some printed copies as soon as possible,” he adds.

Beyond the economic loss for Belmont, some rental scores included annotations made over the decades by great orchestras, and this information is now lost forever. A significant amount of Schoenberg's documents is preserved at the Arnold Schoenberg Center in Vienna. However, objects intimately tied to the composer were lost in the fire, such as a paper cutter he owned and a foot stool he made. These objects were part of a working desk until the fire. “The original flexatone of Schoenberg was lost, among other things, in the fire,” laments the composer's grandson.

Despite the ashes, Schoenberg's work continues to burn in the minds of those who cherish his music, indestructible and eternal.

Comments