A true musical landmark of the 20th century, Maurice Ravel’s Boléro is still the subject of legal disputes despite entering the public domain in 2016. The heirs of collaborators, such as decorator Alexandre Benois, are seeking to have their role in the creation of the work recognized in order to extend the copyright protection and associated revenues.

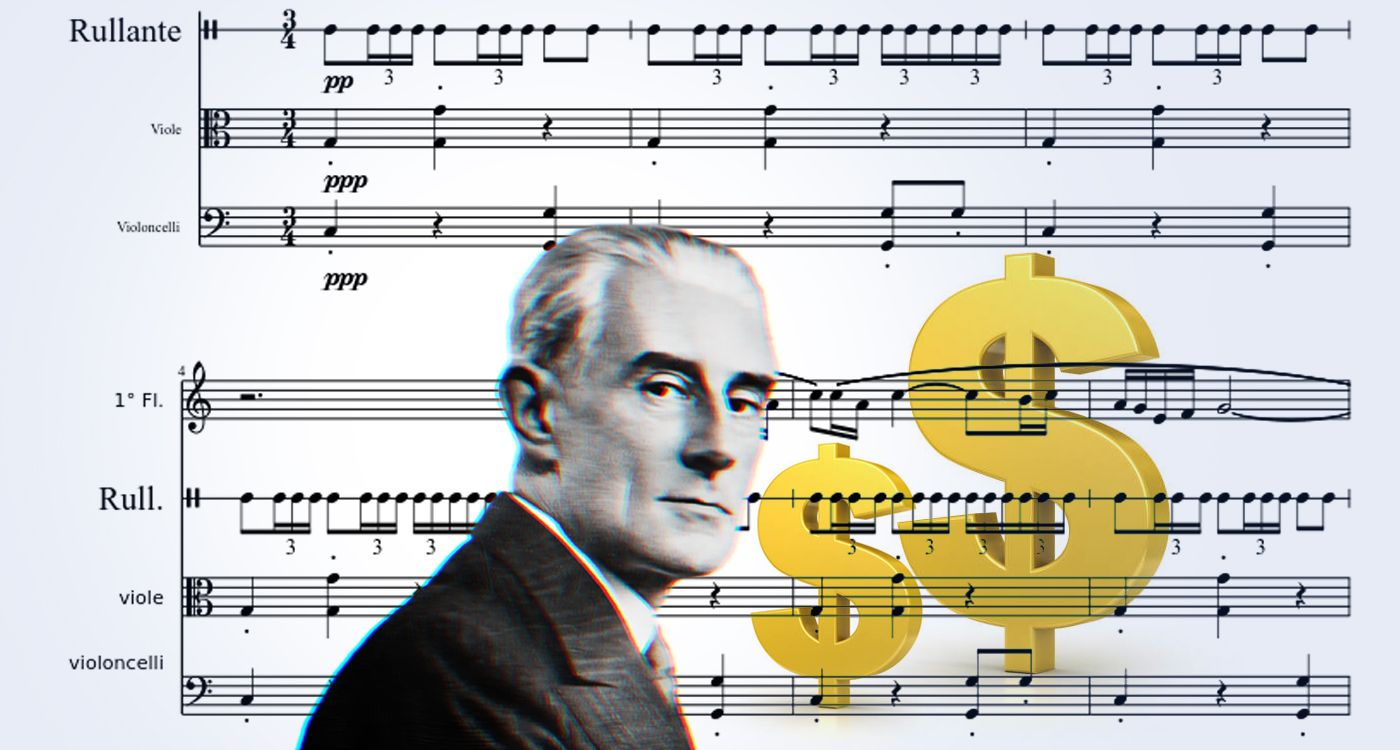

In 1928, at a time when the artistic world was in full effervescence and musical experimentation was at its peak, Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) composed his Boléro (M.81), a work that would quickly become one of the most famous pieces of Western 20th-century art music. Commissioned by the Russian dancer Ida Rubinstein for a ballet, the piece initially seems almost mechanically simple, with its repetitive structure and uninterrupted orchestral crescendo. Yet, this orchestral writing conceals remarkable compositional boldness: Ravel pushes the boundaries of orchestration, gradually layering new textures and instrumental colors with each repetition of the theme. In 2025, as the 150th anniversary of the French composer's birth is celebrated, Boléro remains embroiled in a controversy over copyright, which persists even after the work entered the public domain in 2016.

Legal Debate

Recently, the heirs of Russian decorator Alexandre Benois (1870-1960), who collaborated on the project, and the composer’s heirs contested in court the assertion that Ravel is the sole author of Boléro. Benois’ heirs, who argue that he contributed to the creation of the piece, appealed the ruling in late November 2024, hoping to continue receiving revenue generated by it. As long as the work is protected by copyright, the rights holders can earn royalties, particularly through the Society of Authors, Composers and Music Publishers (SACEM). Although revenue from the work has declined from its peak years, it remains substantial. Between 2011 and 2016, Boléro brought in an average of €135,507 annually for SACEM. Since it entered the public domain in 2016, the heirs of Ravel and Benois no longer receive financial benefits from it, reigniting the legal debate.

Attribution Dispute

It is essential to determine whether Alexandre Benois can be recognized as a co-author of Boléro, which would allow the rights holders to extend the work's copyright protection for 70 years after his death. Taking into account the law compensating French artists for losses during the two World Wars, this period would be extended until 2039.The Nanterre court rejected this request in June 2024, ruling that the evidence presented by Benois’ heirs did not demonstrate his role as a creator. Additionally, the court dismissed the possibility of choreographer Bronislava Nijinska (1891-1972) having contributed to the creation of the ballet. This dispute raises a fundamental question: how do we attribute contributions to a collective work and determine the boundaries of copyright protection, especially when some heirs are attempting to claim rights that do not belong to them? Such legal battles, driven by clear financial motives, are unfortunately common in the arts and music scenes, where the creator’s work often becomes a pretext for excessive patrimonial claims.

Orchestral Crescendo

Far from these financial concerns, Ravel’s Boléro remains a masterpiece, its artistic value far surpassing the issues related to its posthumous copyright. Formally, it is a series of variations around the same melodic theme, characterized by minimal harmonic progression and a steadily intensifying orchestration. The piece is built on an incessant rhythmic ostinato, initially played by the snare drum, which serves as the guiding thread throughout the composition. This regular rhythm, combined with a repetitive structure, gives Boléro an obsessive quality, where the focus is on the evolution of the orchestral texture rather than harmonic development. The musical theme, repeated 18 times, is successively performed by different groups of instruments within the orchestra. This continuous repetition generates a growing sense of tension, ultimately culminating in a powerful and expressive sonic explosion at the end of the piece.

Comments