- Home

- Middle East

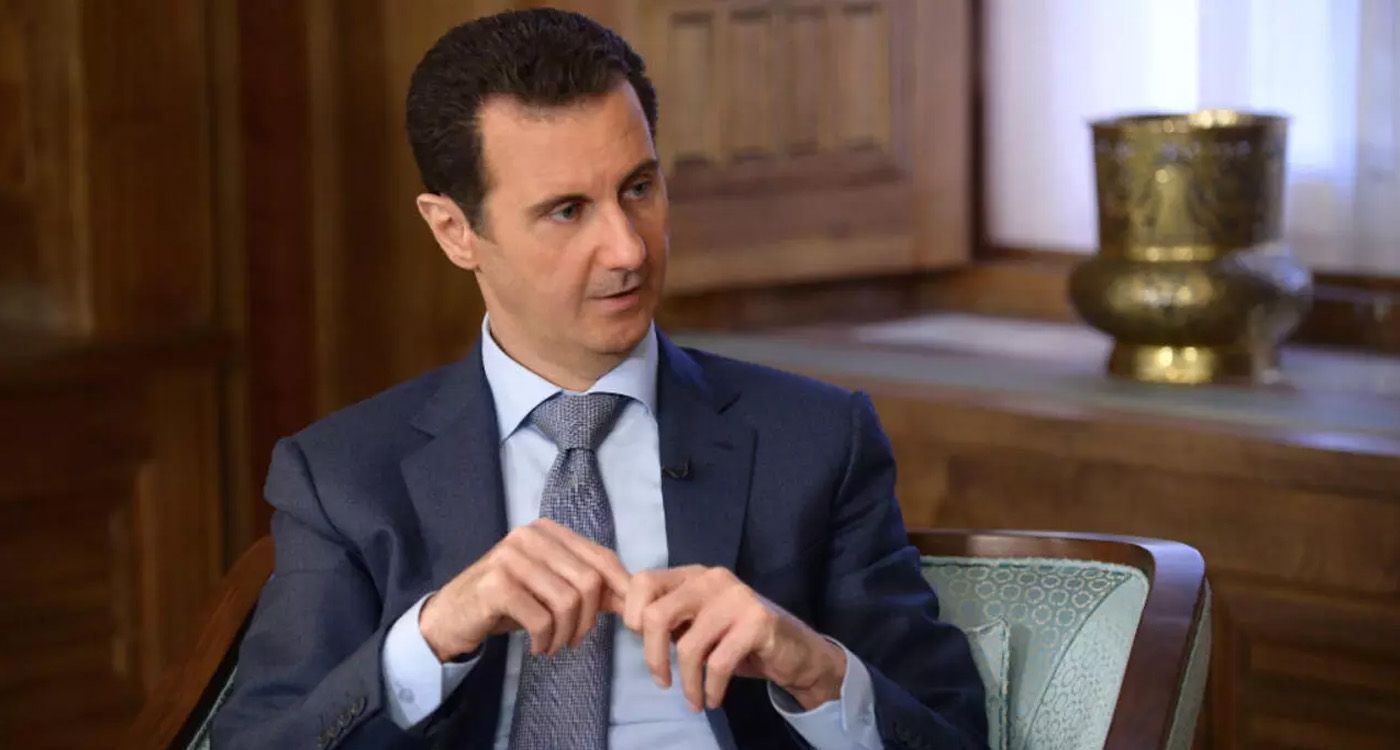

- Can Bashar al-Assad Be Judged for His Crimes?

©SANA / HO / AFP

War crimes, crimes against humanity, the use of chemical weapons against civilians… The accusations directed at former Syrian President Bashar al-Assad raise pressing questions, particularly following the fall of his regime on December 8: can he be brought to justice? If so, through what legal mechanisms? And what about the status he enjoys in Russia?

In theory, several mechanisms pave the way for the possibility of bringing Assad before the courts.

First, the International Criminal Court (ICC). This international body is competent to try war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. However, it does not have automatic jurisdiction over crimes committed on Syrian territory. Why? Because Syria has not ratified the Rome Statute, the founding treaty of the ICC. An alternative would be for the United Nations (UN) Security Council to refer the case to the ICC for investigation. Yet, another obstacle arises at this level. Russia and China, permanent members of the Security Council, have regularly vetoed any resolution aimed at sanctioning or prosecuting the Syrian regime. This protection, for now, blocks any recourse to the ICC.

“On the international level, even though the ICC is not, in principle, competent (for the aforementioned reasons), there is certainly the possibility to study the Myanmar case,” highlights Professor Eric Canal-Forgues Alter, a public law scholar, professor of international public law and diplomacy, former UN official and Dean of the Anwar Gargash Diplomatic Academy (Abu Dhabi), in an interview with This is Beirut. “Faced with a similar challenge in Myanmar, the ICC prosecutor focused on the massive and forced expulsion of Rohingya (a persecuted Muslim minority group) into Bangladesh (a state party to the ICC), carried out by the Myanmar military,” he says, adding, “Today, the prosecutor of the international legal body is seeking an arrest warrant against Myanmar’s junta leader. A similar argument could establish the ICC’s jurisdiction over senior Syrian officials, including Assad, for atrocities that forced hundreds of thousands of Syrians to flee to Jordan, which has ratified the Rome Statute.”

Second, an ad hoc international tribunal. In this context, a special tribunal could be established by the UN, similar to those created for the former Yugoslavia (International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia – ICTY) or Rwanda (International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda – ICTR), specifically to investigate crimes in Syria. However, this option would require the approval of the Security Council, where Russian and Chinese vetoes remain a major obstacle.

Third, national jurisdictions under the principle of universal jurisdiction. “There are possibilities to hold senior officials of Assad’s fallen regime accountable, including Assad himself – who no longer enjoys the immunity granted to heads of state since his overthrow – for atrocities committed in Syria. However, this would require decisive action by the international community or individual states,” explains Professor Canal-Forgues Alter. “This has already occurred, for example, in France and other European countries (especially Germany), under the principle of universal jurisdiction, which allows a nation to prosecute the perpetrators of the most serious crimes regardless of their nationality or where the crimes were committed,” he notes. Indeed, some countries, such as Germany and France, apply the principle of universal jurisdiction, enabling their courts to prosecute perpetrators of serious crimes even if committed abroad and without direct connection to the country. In 2021, a German court convicted a former Syrian officer for crimes against humanity, paving the way for further prosecutions. However, for Assad to be tried under this framework, he would need to leave Syria and travel to a country willing to prosecute him.

Fourth, a trial in Syria after a regime change. The collapse of Assad’s regime now paves the way for the formation of a new government that could decide to prosecute the former president in a national court. According to Professor Canal-Forgues Alter, “this is possible, provided negotiations with the new regime are conducted regarding their appropriateness and feasibility.” However, the support of Assad’s Russian and Iranian allies makes this option highly speculative.

What Status Does Assad Have in Russia?

As Assad’s primary international supporter since the beginning of the Syrian war, Russia enabled the deposed head of state to regain much of Syrian territory through its military intervention in 2015. This support extends beyond the battlefield, with Moscow also shielding Assad diplomatically, particularly by blocking any international efforts to prosecute him.

Today, Assad has found refuge with his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin. He reportedly enjoys the status of a political refugee, or even special protection offered by Moscow as a strategic ally. While Russia has yet to publicly acknowledge such plans, history shows that the Kremlin has previously granted refuge to other deposed leaders (such as former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych in 2014). “Thus benefiting from asylum in Russia, which is not a party to the ICC, it is highly unlikely, if not impossible, to obtain Assad’s extradition. However, he can still be tried in absentia,” notes Professor Canal-Forgues Alter.

The trial of Assad raises fundamental issues for international law and the fight against impunity. Although the path to justice currently seems fraught with obstacles, such an endeavor is not beyond reach. One only needs to recall that leaders once deemed untouchable eventually appeared before the courts.

Read more

Comments