In this fifth and final article of our series dedicated to the City of the Sun, we look back at three historic concerts held in 1969 during the Baalbeck Festival, where Sviatoslav Richter and Mstislav Rostropovich offered the Lebanese public exceptional performances. These moments of eternity recall the golden age of (so-called) classical music, where technical excellence served the soul of the work. It was a time when interpretation was still a profound act of connection and communion.

“It is not the path that is difficult; it is the difficult that is the path.” This aphorism from the great Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) illustrates, through its paradox, the contrast between effort and goal, discipline and freedom. This reflection is entirely fitting within the domain of classical music, especially when considering how interpretation has developed over time. In the past, musical performance was based on absolute rigor, dictated by the score and the composer’s intent. The path, both arduous and demanding, acted as a sieve, retaining only those who truly deserved to access it, inevitably leading to an authentic and profoundly human form of expression. Today, however, this path seems to have been redefined. What was once an act of communion between the work, the artist and the audience increasingly seems to have become a demonstration of technical skill, where the search for immediate effect now takes precedence over the soul of the music. Yet, not all that glitters is gold.

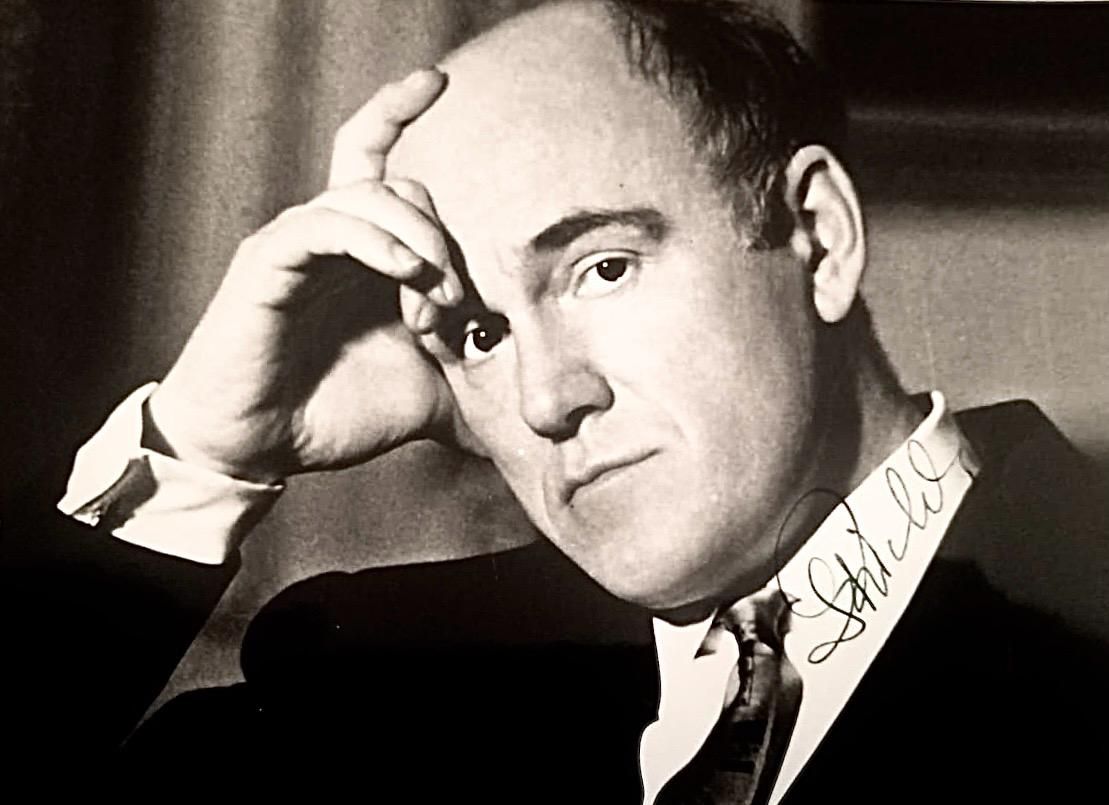

The fifth and final article in our series, dedicated to the City of the Sun, focuses on three historic concerts held in 1969 at the Baalbeck Festival, featuring two princes of musical interpretation: the Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter (1915-1997) and the Soviet cellist Mstislav Rostropovich (1927-2007), known as Slava. They were among the last representatives of an era that is rightly called the golden age of music, where the quest for authentic expression was not only seen as a necessity, but as an imperative, even a true cult.

A Message of Continuity

"Since the founding of the Baalbeck Festival in 1956, Aimée Kettaneh had been its president. After twelve years in office, in 1969, and without informing her, the Committee decided to appoint a new president. Salwa Saïd was then elected to succeed her and presided over the Festival from 1969 to 1972, continuing the same tradition as her predecessor,” wrote the late pianist Henri Goraïeb (1935-2021) in his correspondence with the author of this article. That year, two renowned Soviet artists, Richter and Rostropovich, were invited to the Baalbeck Festival, each performing a concerto with the Gewandhaus Orchestra of Leipzig, conducted by Kurt Masur. A prominent figure in East German musical life, Masur would later play a key role in the events that led to the fall of the Communist government in late 1989. Notably, Rostropovich’s impromptu recital (after being stripped of his Soviet citizenship in 1978 for "acts systematically detrimental to the prestige of the Soviet Union") at the Berlin Wall, at the symbolic crossing point from East to West, on November 11, 1989, became a powerful symbol of regained freedom after the fall of the Wall and marked the end of an era.

On August 7, 1969, the cellist arrived by helicopter at the Temple of Bacchus, while the audience was already seated and the orchestra took its place on stage. No rehearsal had taken place before the concert. The evening’s program was of great diversity: Triptych for Orchestra by Otto Reinhold (1899-1965), Symphony No. 1, Op. 38 by Robert Schumann (1810-1856), and, of course, the famous Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104 by Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904), a masterpiece that is now irrevocably associated with Rostropovich’s virtuosity. Nearly three decades later, on July 31, 1997, after the end of the so-called Civil War, he returned to the land of the Cedars to perform this concerto again, reconnecting with a memorable past. He said in 1997, “Baalbeck is, for me, an unforgettable place, and its beauty carries great spiritual strength. I suffered a lot with you throughout your years of hardship, and that is why I have chosen today to play the same concert I performed nearly thirty years ago in 1969, as a message of continuity from a beautiful era.”

“Rostropovich was an extraordinary cellist,” says French composer Éric Tanguy to This is Beirut. “He had a perfect mastery of the instrument; all musicians celebrated the ‘Rostro’ sound, unique, powerful and instantly recognizable in his sublime phrasing. He had such an intense connection with creation, telling me that when he had to perform a new composition, it became the most important thing in his life.” Tanguy continues, “Rostropovich was a man of immense generosity. I will never forget the chance he gave me when he commissioned and performed my second cello concerto several times.”

A Magical Journey

On August 9, 1969, it was Richter’s turn to enchant the Lebanese public, still under the baton of Kurt Masur, in a concert decidedly Germanic in nature. The program included Beethoven's Symphony No. 7, Op. 92, an emblematic work of Beethovenian grandeur, and Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 83. Filled with a wide range of emotions, from burning passion to intimate melancholy, this romantic work perfectly blends pure emotion with musical complexity. “It was one of the most beautiful days of my life, confides Lebanese-French concert pianist Billy Eidi. A magical journey, where we crossed Lebanon from side to side, from the early hours of the day, traversing the mountains before descending into the Beqaa Valley, to finally arrive in Baalbeck, with a mandatory stop in Chtoura, where we’d have a slice of labneh. It was an expedition we loved to make. As an encore, Richter replayed the sublime final of this magnificent concerto.”

A day or two later, the Carlton Hotel in Raouche hosted a private recital, where Richter performed sixteen preludes and fugues from the first book of The Well-Tempered Clavier by J.S. Bach, from numbers 1 to 8, and then from numbers 17 to 24. “This concert deeply marked me, and it was at this recital that my overwhelming love for Fugue No. 18 in G-sharp minor, BWV 863, was born. Throughout the summer, I began to sing the theme of this fugue morning and night,” recalls Billy Eidi, now a piano professor at the Schola Cantorum in Paris. He continues, “Richter entered the stage with a score in a thousand pieces, which he simply placed on the stand without ever opening it. We were in a state of ecstasy. It was my teacher, Zafer Dabaghi, who gave me a ticket she had received as a prominent musical figure in Beirut, and I accompanied her.” Eidi believes that the rare “happy few” present that evening had the privilege of witnessing one of the greatest piano legends, performing some of the most beautiful, richest and deepest works in the piano repertoire. “A moment that marks an adolescent for life,” he concludes, moved.

That evening, at the end of the concert, the young Robert Lamah, then a piano student at the National Conservatory in the class of Wadad Mouzanar, was chosen to present the bouquet to the Soviet pianist. “I had the honor of shaking his hand,” remembers the Lebanese-British pianist, former disciple of great international interpreters such as the Russian Victor Bunin, the Polish Ryszard Bakst and the Hungarian Louis Kentner. The impression I have of him is one of great kindness, and above all, humility. That brief moment was imbued with rare intensity.” On August 14, Richter gave another concert, this time solo, at the Baalbeck Festival. He performed Thirteen Variations on a Theme by Hüttenbrenner, D. 576 by Franz Schubert (1797-1828), six of the eight pieces from Fantasiestücke, Op. 12 by Schumann and twelve Preludes by Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943). “He had unlimited resources: energy, strength and so much love in his playing. And on top of that, he was a true encyclopedia of the piano,” says Robert Lamah.

It was a beautiful era. An era when Baalbeck wrote the most beautiful chapters of its history in golden letters.

Comments