A soul utterly devoted to music, Henri Goraïeb left his mark on the 20th century, illuminating international stages from the Middle East to Europe, from Russia to India. In this third article in our series, we pay tribute to the exceptional journey of this “living musical encyclopedia,” marked by his first triumph at Baalbeck. A triumph that was only the prelude to a series of international successes, driven by an incessant quest for musical truth and a modesty that often concealed a talent of rare finesse.

Some souls pass through this world like a shooting star, leaving behind a light that never fades. They are born in silence and return to the original silence. On tiptoe, it is said. Henri Goraïeb (1935-2021) was one of them. A concert pianist — and, oh, what a virtuoso — he was one of those candles that burned stoically despite the contrary winds, illuminating with their presence a musical landscape that gradually crumbled under the weight of the ephemeral and the trivial. An artistic world that feels the need, even the urge, to destroy itself. The image is dark, we agree, but how can one avoid this observation when witnessing, helplessly, the collapse of this “revelation higher than all wisdom and all philosophy,” to borrow Beethoven's expression?

The rot had been in the fruit for decades, slowly festering within Western art music, which was losing its bearings. But Henri Goraïeb, for his part, knew how to bite elsewhere. He fled corrupted obviousness to draw from still fertile lands, where music retained its first breath. He was one of those Don Quixotes of the piano, fighting the windmills of a world where the search for musical truth seemed to have been lost. Where others complacently rested in ease, he persisted in searching, exploring, dreaming, digging, over and over again — intuitively making his piano “sing,” as he liked to say, continuously reviving masterpieces that an overwhelming modernism sought to bury. And we know, alas, the price to which honest men are condemned.

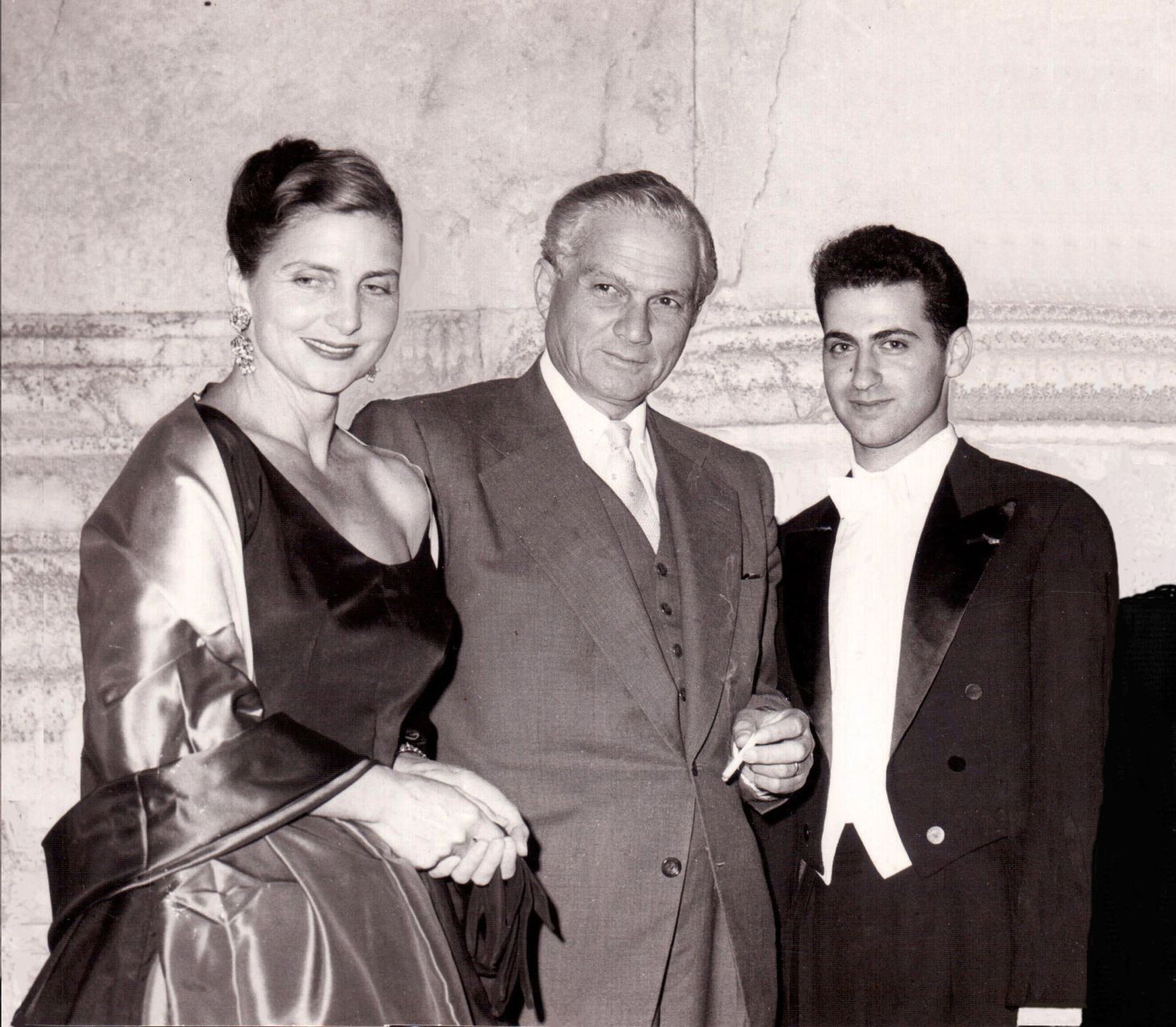

The third article in our series, dedicated to the City of the Sun, honors this “living musical encyclopedia,” to quote Polish pianist and composer Milosz Magin (1929–1999), a long-time friend of Henri Goraïeb. It focuses on his two concerts at the Baalbeck Festival in 1956 and 1957 — performances that offered a taste of eternity to many demanding and refined souls, including Charles Munch (1891–1968), one of the most sensitive conductors of his century.

Impromptu Selection

July 1956. Following the success of the previous year, the Baalbeck Festival was preparing to lift the curtain on its second edition. Among the honored guests was none other than Wilhelm Kempff (1895–1991), whose elegance and mastery of the piano remained undisputed, although he seemed somewhat overshadowed by the emergence of new great musical figures, notably Sviatoslav Richter (1915–1997) and Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (1920–1995). However, it was another concert that particularly captured the attention of music enthusiasts that year: Firebird by Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971), performed by the NDR Hamburg Orchestra, conducted by Léon Barzin (1900–1999). Everything seemed ready for the mythical bird to take flight at Baalbeck — almost. The piano part, essential to the work, still lacked a designated performer.

“I timidly mentioned that I knew the piece, and I was invited to play it,” Henri Goraïeb recalled in his correspondence with the author of these lines, who is none other than his biographer. Thus, on July 31, 1956, on the steps of the Temple of Bacchus, the 21-year-old pianist brilliantly performed with the German orchestra. He especially rose to the challenge by infusing the energy and vigor necessary to magnify the exalted spirit of this quintessentially Russian work, which precedes the earthquake, or even the scandal, of The Rite of Spring. The piano blended harmoniously with the ensemble, accentuating the orchestral colors and shimmering effects. A perfect symbiosis that revealed Stravinsky's genius in sculpting timbres. Although modest, Henri Goraïeb’s performance garnered attention from the press, which gave him unanimous praise. His performance even overshadowed that of the remarkable pianist Aldo Mancinelli (1928–2020), soloist in Anis Fuleihan’s Piano Concerto No. 2 (1900–1970). The evening also featured Mozart’s Symphony No. 35 in D major, K. 385 (known as the "Haffner"), conducted by Barzin.

Historic Concert

“This performance earned me great success both with the public and the press. I cannot say whether it influenced Mme Aimée Kettaneh and the Baalbeck Festival Committee to invite me, for the next edition, to perform a concert with orchestra,” Henri Goraïeb wrote. The project materialized in August 1957, when the pianist was invited to perform Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54, with the Orchestra of the National Academy of Santa Cecilia of Rome. “However, this choice was not met with approval by Anis Fuleihan, then director of the Lebanese National Conservatory, who suggested the inclusion of violinist Varoujan Kodjian and pianist Diana Takieddine in the program,” the virtuoso added. The rest belongs to history and musical criticism.

That year, the Baalbeck Festival hosted two renowned musical figures: Charles Munch, one of the most illustrious conductors on the international stage, and Fernando Previtali (1907–1985), whose name is inseparable from the Italian repertoire. The latter was tasked with conducting the orchestra during Henri Goraïeb’s concert. “Munch was furious that I wasn’t entrusted to him,” Goraïeb remarked. The French conductor, however, attended the concert and was impressed by the level of the soloist’s performance, characterized by great technical mastery but above all, expressiveness. Indeed, Schumann’s concerto has a very pronounced Romantic flavor, highlighting the intimacy of the dialogue between the piano and the orchestra. This is particularly emphasized in the first movement (Allegro affettuoso), where the refined writing for the solo winds contrasts with the pianistic discourse that invites careful listening to nuances and sonic colors. The Intermezzo of the second movement explores a variety of introspective moods before seamlessly blending into the joyful finale.

A Radiant Prelude

The concert almost touched the sublime. A triumph. “Munch showed me an esteem that moved me for the rest of my life. He even took the trouble to send a little note to Marguerite Long to tell her about my performance,” the Lebanese-French pianist recalled. “Dear, dear friend. I just heard a young Lebanese pianist who played Schumann wonderfully. His name is Goraïeb. Another one who plays so well because he is one of yours. With all my deep affection, your Charles,” he wrote in his letter. At that time, Henri Goraïeb was a disciple of Marguerite Long (1874–1966), a French pianist of international renown, recognized for her interpretation of the great classical repertoire and her influential role as a pedagogue in the world of piano music.

This first dazzling success at Baalbeck would be just the prelude to a series of triumphs that would profoundly mark his career, notably in France and Luxembourg with Louis de Froment (1921–1994), across Europe with prestigious orchestras (the Luxembourg Philharmonic Orchestra, the French National Radio Orchestra, the Bucharest Symphony Orchestra, among others), in the Soviet Union, where one of his concerts was broadcast by national radio, as well as in India and the Middle East, including Lebanon. “His modesty always concealed his pianistic talent, as a recitalist, concert artist and accompanist. And that talent was very great, as were his repertoire and musical culture,” shared Gilles Cantagrel, a leading expert on Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) and former director of France Musique, where Henri Goraïeb hosted a series of shows in the 1980s: Les Archives lyriques, Premières loges, Voix souvenirs, Les Voix de la nuit and D’une oreille à l’autre.

If Poland had Arthur Rubinstein (1887–1982), Italy had Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, France had Alfred Cortot (1877–1962) and the Soviet Union had Emil Gilels (1916–1985), Lebanon had Henri Goraïeb. Requiescat in pace, Maestro.

Comments