A surrealist masterpiece by René Magritte, the series The Empire of Light brilliantly explores the contrast between day and night. A striking fusion of paradoxical elements, it subtly disorients the viewer, standing in stark contrast to the flamboyant approach of Salvador Dalí.

The Empire of Light by René Magritte undoubtedly ranks among the most fascinating pictorial series of the 20th century. An emblem of the singular artistic approach of the Belgian surrealist master, it embodies his relentless quest to challenge our certainties about reality and its representation. Created over three decades, from 1940 to 1960, the series includes no fewer than 27 variations—17 oil paintings and 10 gouaches. A testament to its significance: one of these iconic works recently shattered auction records at Christie’s in New York on November 19, 2024, reaching the staggering sum of $121,160,000.

A Striking Visual Paradox

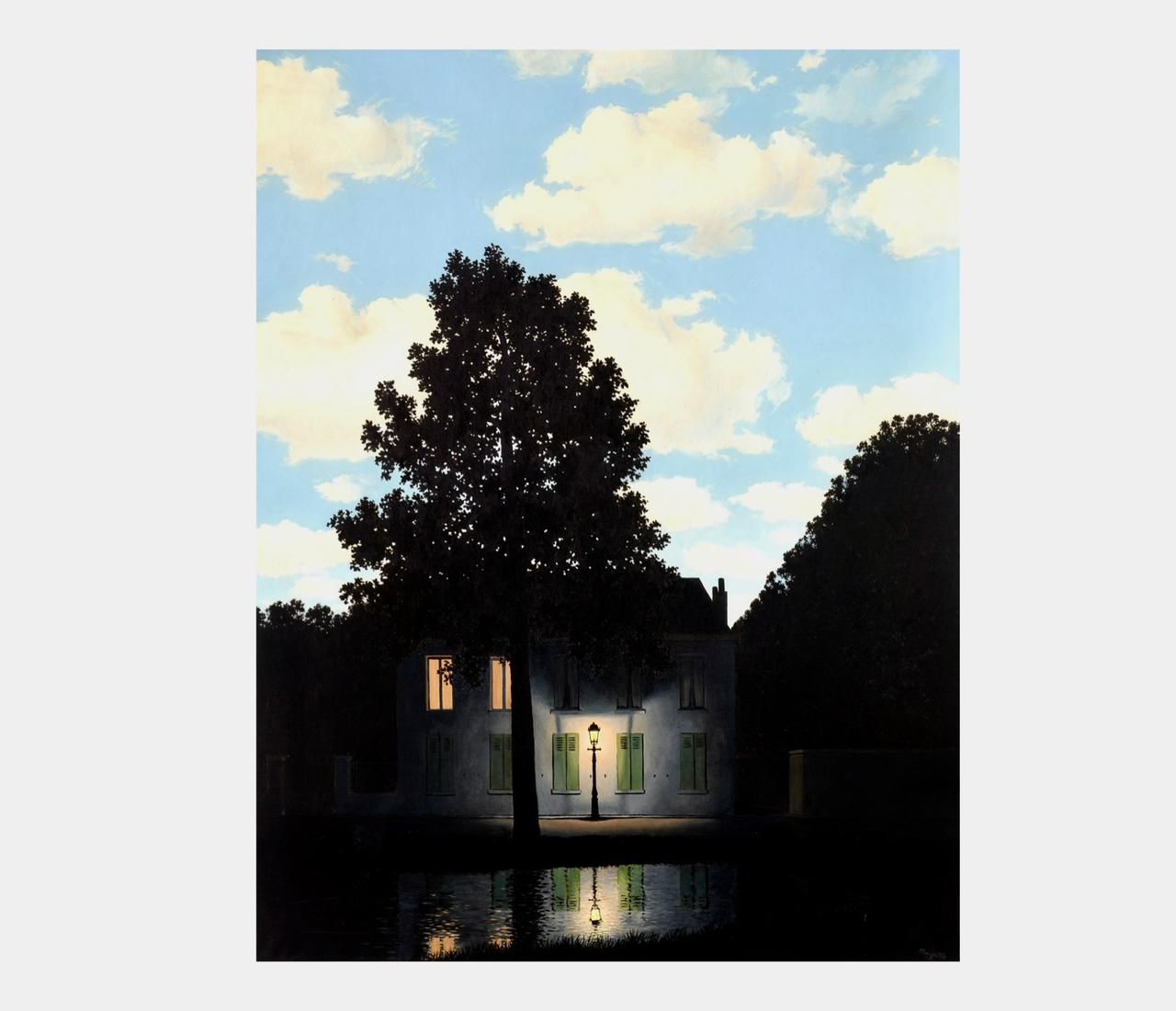

The power of this series lies in the visual shock it instantly provokes in the viewer. Magritte juxtaposes two theoretically irreconcilable elements: a serene nocturnal landscape, featuring a house illuminated by a solitary streetlamp and glowing windows in the dark, overshadowed by a radiant daytime sky, vibrant blue and scattered with white clouds. This radical contrast between day and night, illogically united in a single image, creates an immediate aesthetic tension. The eye, accustomed to a certain coherence, is suddenly caught off guard, disoriented by this enigmatic vision that defies common sense.

But beyond its purely visual impact, The Empire of Light invites deeper reflection on the very nature of reality and how we perceive it. By disrupting our familiar points of reference, Magritte encourages us to question what we typically take for granted. He suggests that the world may not be as obvious or unambiguous as it seems. Beneath the apparent banality of everyday life, hidden mysteries await discovery—for those willing to view it with fresh eyes. This is the genius of Magritte: transforming the familiar into the extraordinary, imbuing the ordinary with a “formidable and charming depth.”

This series is all the more captivating because it lends itself to multiple interpretations. The illuminated house in the night can be seen as a metaphor for individual consciousness, awake in the midst of a sleeping world. Alternatively, it might represent a secret nocturnal life, in opposition to the daylight clarity of social appearances. The solitary streetlamp evokes the quest for knowledge, the light of reason piercing the darkness of ignorance. As for The Empire of Light itself, it could signify the reign of day triumphing over shadows or the mind liberating itself from the illusions of the sensory world. These interpretative pathways demonstrate the symbolic richness of the work.

Magritte and Dalí: Two Approaches to Surrealism

To fully appreciate the originality of The Empire of Light, it’s useful to compare it to the work of another great surrealist: Salvador Dalí. While both Magritte and Dalí belong to the "veristic" strand of the movement, characterized by figurative representations rendered fantastical or impossible, their approaches differ radically. Dalí fills expansive landscapes with microscopic details in a flamboyant, almost hallucinatory hyperrealist style. In contrast, Magritte opts for pared-down compositions, almost classical in their simplicity, where strangeness arises from the subtle discord between otherwise perfectly realistic and recognizable elements.

While Dalí's melting clocks spectacularly dissolve time, Magritte's collision of day and night involves a more discreet mental distortion, almost imperceptible at first glance. It is this restraint, this economy of means, that gives his images their enduring power to astonish. Less immediately flashy than Dalí’s works, they are no less oppressive, imbued with a diffuse existential anxiety beneath their calm appearance.

Now housed in the world’s most prestigious museums—from MoMA in New York to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice and the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium—paintings from The Empire of Light have achieved iconic status in 20th-century art. Their influence extends far beyond the artistic realm: they have inspired filmmakers like William Friedkin, who explicitly cites Magritte as a major influence on his cult film The Exorcist. Further proof, if needed, of the timeless evocative power of these unclassifiable works.

Combining conceptual strangeness with pictorial mastery, The Empire of Light embodies the visionary genius of René Magritte. A disturbing mirror held up to our perceptions, this enigmatically beautiful series continues to challenge our understanding of existence. An inexhaustible invitation to question, it radiates a quasi-mystical aura that explains its universal appeal. Few works can so masterfully reconcile opposites as this one does.

Comments