Every week, we invite you to explore a striking theme to reveal its depth and richness. These lapidary, often provocative formulas open up new perspectives on the intricacies of the human psyche. By deciphering these quotes with rigor and pedagogy, we invite you on a fascinating journey to the heart of psychoanalytic thought to better understand our desires, anxieties and relationships with others. Ready to dive into the deep waters of the unconscious?

"The good only dream of what the bad actually do."

This quote from Plato, later referenced by Freud, could be seen as an epitome of The Interpretation of Dreams, the cornerstone of Freud's theory that a dream is a disguised fulfillment of a repressed desire. For Freud, dreams, like fantasies, play a crucial role in the human unconscious. Repressed desires and unconscious thoughts often reveal themselves during sleep.

Beneath the façade of those who consider themselves “good” lies an array of unspoken urges that find an acceptable outlet in dreams. These individuals may dream or fantasize about immoral or forbidden acts without actually carrying them out. The "bad," on the other hand, succumb without restraint to their destructive urges, acting them out in reality. Surface morality and real-life violence on one hand, versus instinctual satisfaction in dreams or fantasies on the other: this is the dichotomy Freud highlights with striking clarity.

In reality, beyond this dual vision, Freud suggests an unsettling truth: both "good" and "bad" share the same instinctual nature. The fate of these drives alone differs—repression and dream distortion for some, direct action for others. Dreams thus emerge as a powerful mechanism of psychic regulation, a “royal road” to the unconscious that governs us unknowingly.

Psychoanalysis rejects the idea of a natural goodness in humanity, an ideal naively upheld by J-J. Rousseau. For Freud, this is a “dangerous illusion,” for the “wild beast” lies dormant within each of us. Kindness and benevolence prove to be the fruits of rigorous psychic work under the guidance of a conscience that has internalized moral values. The feeling of being "good" often comes hand-in-hand with guilt; they appear as two sides of the same coin.

As for wickedness, it can be defined as the conscious and deliberate desire to make others suffer. Self-centeredness, envy, blind conformity, or serious instinctual conflicts are its roots, and harassment, passive or active aggression, and common sadism are its daily expressions. At its core, wickedness reflects a rupture with otherness and a fixation on archaic instinctual satisfactions.

The other key actor behind the duality of good and bad is fantasy. In dreams, it represents the disguised realization of an unconscious desire, weaving psychic elements into a hallucinatory storyline that can fulfill the dreamer’s desire without their awareness.

Outside of dreams, fantasy takes on the more conscious form of imaginary scenarios, daydreams. Lacan sees it as a protective screen raised against an unbearable reality and the enigmatic desire of the Other. While dreams open onto reality, fantasy invites it in on tiptoe, “plugging the gap of desire” through a neurotic construction. The psychoanalyst elaborates on this idea by explaining that, while reducing anxiety, fantasies act as a shield against the Other’s desire, which looms as a threat of annihilation. In this way, fantasy offers a safe space where one can explore desires without being overwhelmed by others. As Lacan writes: “The function of fantasy is to set a limit on desire. It serves as a barrier that prevents the Other’s desire from engulfing the subject.”

Fantasy has also been described as a “psychic prosthesis,” allowing a person to experience themselves as the object of the desire of an absolute Other. It transforms the distressing lack in the Other into a simple demand to which one can present oneself as the answer. The analytic process can dismantle this scaffold of fantasy to reveal the irreducible lack at the core of the Other.

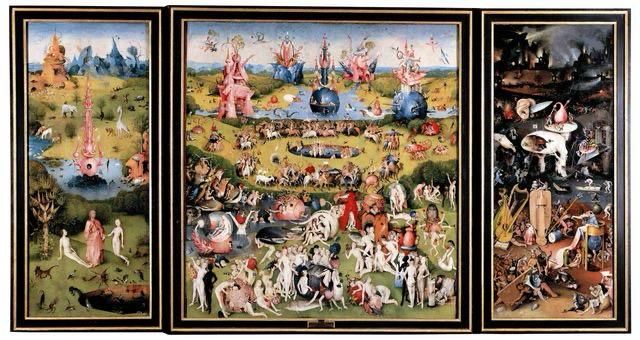

In The Garden of Earthly Delights, the Dutch primitive painter Hieronymus Bosch offers a striking illustration of fantasy’s function, which constitutes the hidden garden of each person. One almost feels immersed in a waking dream or nightmare. His triptych, vertiginously rich in artistic skill and knowledge of hidden desires, juxtaposes three panels: the creation of the world, the Garden of Eden, and hell. The central panel, the realm of fantasy, displays a chaos governed by the logic of dreams, where the most unbridled erotic symbols intermingle. It’s the Garden of Delights, a closed world without shadows. It depicts a psychic space where desire is arranged in delirious order, where instincts seek an impossible reconciliation with the Law. Bridging two worlds, Bosch’s work reveals fantasy as an attempt to give shape and meaning to the magma of drives.

It is this same central panel that crystallizes fantasy’s function. It presents an apparent disorder that nevertheless follows a dreamlike logic, centered around a fountain of life. The dreamlike symbols are abundant: fantasies as darts, thorny sticks, ovoid bubbles, scenes of nudity and acrobatics suggesting amorous play, unbridled eroticism, and an extraordinary amalgamation of plant, animal, and mineral kingdoms. All this sheds light on fantasy’s protective function. Fantasy creates a structured imaginary world in the face of chaos, representing an attempt to organize and give meaning to desire. Bosch illustrates fantasy as a psychic construction attempting to manage the upheavals of desire while protecting the subject from its potentially destructive nature.

Dream and fantasy are salvific screens raised against reality, protecting us by revealing both the past and future of a subject shaped by an unconscious that guides as much as it misleads. Psychoanalysis relentlessly questions these certainties, confronting us with the riddle at the core of our being: What does the Other desire within us?

Comments