Once a vibrant center of Urdu literature in Old Delhi, the iconic Urdu Bazaar is now struggling to survive. Declining readership, cultural shifts, and the digital age have left its bookstores fighting for relevance in a changing India.

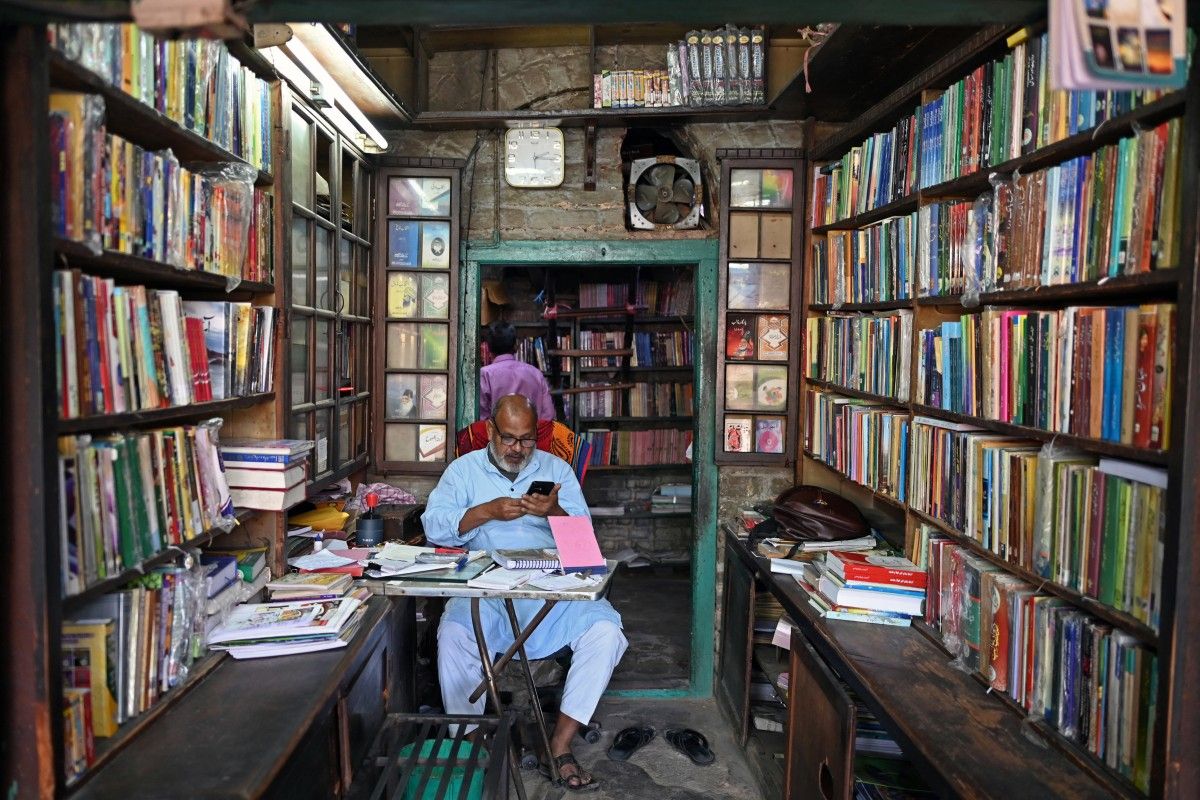

In the heart of Old Delhi, bookseller Mohammed Mahfooz Alam sits in his quiet shop, one of the last few stores selling Urdu literature, a language cherished by poets for centuries. Urdu, spoken by millions, carries a rich history reflecting India's complex cultural blend. However, it has steadily declined under the dominance of Hindi, facing misperceptions that its graceful Perso-Arabic script belongs only to Muslims in the Hindu-majority nation. "There was a time when we’d see a hundred books published each year," laments 52-year-old Alam, saddened by the language’s fading readership.

The narrow lanes of Urdu Bazaar, located in the shadow of the 400-year-old Jama Masjid, were once bustling with Urdu literary activity—printing, publishing, and lively discussions. Today, instead of bookstores filled with scholars debating literature, the streets are lined with restaurants serving sizzling kebabs. Only a handful of bookstores remain. "Now, there are no takers," says Alam, gesturing at the streets outside. "It’s become a food market."

Dying "day by day"

Urdu, recognized as one of India’s 22 official languages, is the mother tongue of at least 50 million people in the world’s most populous country, with millions more speaking it in Pakistan. Despite its shared linguistic roots with Hindi, the two languages are written in entirely different scripts, complicating Urdu's widespread appeal.

Alam watches with despair as Urdu literature fades "day by day." The Maktaba Jamia bookshop, which he manages, has been in business for nearly a century. Alam took charge this year, driven by his passion for the language. "I’ve been here since morning, and only four people have come," he says, his voice tinged with resignation. "And they were just students looking for school books."

Urdu, with its blend of Persian, Arabic, and local Indian languages, evolved as a hybrid between traders and conquerors and the local population. However, it is often viewed as linked to Islamic culture, a perception that has intensified since the rise of the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) under Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014. Hardline nationalists have resisted its presence, even objecting to its use in advertisements and street art. "People think Urdu is only for Muslims, but it’s not true," Alam explains. "Everyone speaks Urdu. You go to villages, and people speak Urdu. It’s a sweet language, filled with peace."

Rediscovering the beauty

For centuries, Urdu was central to governance and culture in India. Sellers established the Urdu Bazaar in the 1920s, offering books on literature, religion, politics, history, and even texts in Arabic and Persian. The 1980s saw the slow encroachment of fast-food restaurants, and the last decade’s digital revolution further eroded the book trade. Today, fewer than a dozen bookstores survive.

"The internet made everything accessible on mobile phones," says Sikander Mirza Changezi, who co-founded a library in Old Delhi in 1993 to support Urdu. "People stopped buying books, and sellers turned to other trades."

Changezi’s Hazrat Shah Waliullah Public Library houses thousands of books, including rare manuscripts, aimed at promoting Urdu literacy. Adeeba Tanveer, a 27-year-old Urdu master's student, appreciates the library's role in sustaining interest in the language. "Urdu’s love is slowly returning," she says, noting that her non-Muslim friends are eager to learn. "It’s such a beautiful language. You feel its beauty when you speak it."

With AFP

Comments