The rediscovery of an unpublished waltz attributed to Frédéric Chopin in the archives of the Morgan Library and Museum in New York reignites enthusiasm for his work, sparking an engaging debate about the authenticity of this score and its potential to enrich the musical heritage of the Romantic master. Analysis.

A mysterious yet nostalgic breeze seems to lift the dust of centuries, heralding the arrival of a musical harvest. The recent announcement, made on September 19 in Leipzig, Germany, of the discovery of a seven-movement string trio likely composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) during his youth, between the mid and late 1760s, has sparked excitement in musical circles. While some have expressed enthusiasm, others have remained more skeptical, urging caution. Experts, however, leave no room for doubt: the score is authentic. No sooner was this news absorbed than another recent discovery rekindled passions—and doubts once again.

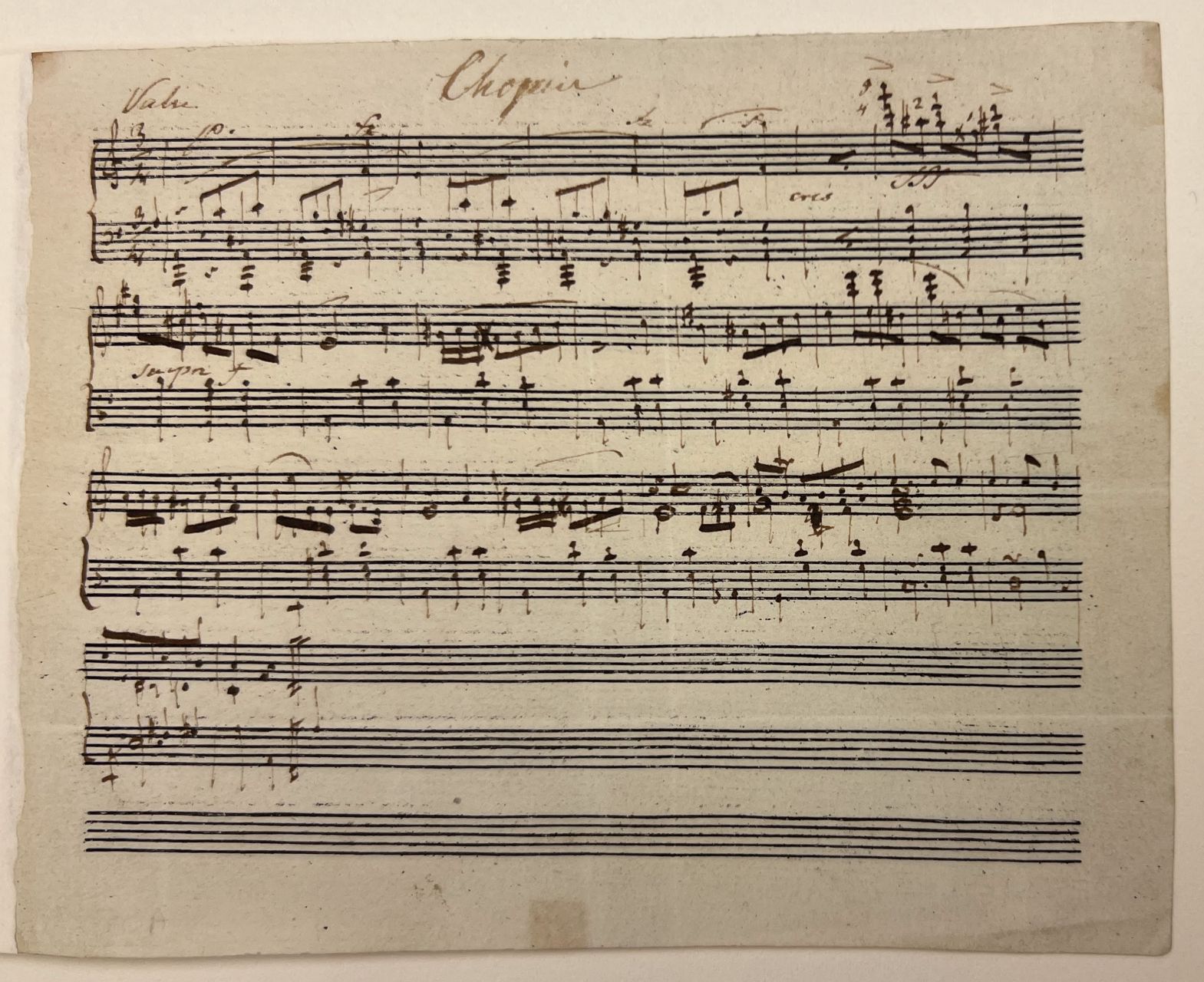

As the musical world has just commemorated the 175th anniversary of Frédéric Chopin's death on October 17, a previously unknown waltz emerges, unearthed in the vaults of New York's Morgan Library and Museum, according to The New York Times. This precious score (until proven otherwise), marked “Valse” in French, was discovered by curator Robinson McClellan during a spring inventory. While cataloging the Arthur Satz Collection, acquired by the Morgan in 2019, he stumbled upon the “Chopin” document, numbered 147. The curator was struck by the inability to link the manuscript's 24 measures to any known waltz by the Polish composer, despite it being identified as such in the collection. Perplexed, he wondered, “What could it be?” After photographing and playing the score on his piano, McClellan remained uncertain about its authenticity.

Thorough Analysis

This doubt led him to consult Jeffrey Kallberg, a Chopin expert at the University of Pennsylvania. Following a meticulous analysis of the manuscript, Kallberg and other experts finally concluded: there is a “strong probability” that the score is indeed Chopin's, according to an October 30 statement by the Morgan. The paper and ink match what Chopin used at the time, and the handwriting is consistent with his, including the unusual representation of the bass clef symbol. The score also bears a scribble, a frequent habit observed in the Polish composer's manuscripts. To learn more, This is Beirut contacted the American museum and examined the unpublished waltz in A minor.

Despite the arguments put forward, several factors could still cast doubt on the manuscript's authenticity. Right away, one might note that the three-time piece, dating from the 1830s according to experts, is significantly shorter than Chopin's known waltzes. Its dissonant opening measures peak in a striking burst before giving way to a melancholic melody. According to musicologists, this start is unusual, perhaps even foreign to Chopin’s style. “My initial reaction is rather skeptical; in this little piece, I see more elements resembling the many pastiches created in Chopin's style than similarities to his true style, especially between 1830 and 1835,” says Abdel Rahman el-Bacha for This is Beirut.

Chopin’s Signature

The 1978 laureate of the Queen Elisabeth International Music Competition of Belgium is one of the few pianists, and the first, to have recorded the complete solo piano works of Chopin in chronological order in 2001 for Forlane. This achievement has established him as an expert in this musical realm. “The harmonic language is very poor: parallel fifths between the melody and the bass, basic modulations. No melodic turn that indicates the spark of genius found even in the slightest of his posthumous works,” the artist explains, adding that, without seeing the manuscript, he cannot offer a more detailed opinion. It is worth noting in passing that Abdel Rahman el-Bacha has also recorded the complete set of Beethoven's 32 sonatas twice — for Forlane (1993) and Mirare (2013) — which were acclaimed by the press as a “major event.”

The Lebanese-British pianist Robert Lamah, a graduate of the prestigious Royal College of Music in London and former student of Ryszard Bakst and Louis Kentner, distinguished interpreters of Chopin, offers a different perspective. “The genius of this piece is mainly reflected in the soul of the composer, which can be felt similarly in some of his smaller mazurkas. Listening to it evokes emotions similar to those in some of his intimate, smaller works," he remarks, referring to Lang Lang’s performance at Steinway Hall in Manhattan, the only available recording of the piece to date. Though the waltz is simple and brief, Lamah believes it immediately reveals Chopin's signature, his soul, and his music. “Whether this piece was written by Chopin or not, it will certainly neither enrich nor deepen our understanding of him as a poet of the piano,” he concludes.

Interesting but Not Groundbreaking

We also contacted Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger, one of the world's leading musicologists renowned for his expertise on Chopin's life and work. “At first glance, it appears to be an autograph, no doubt about it. Upon first hearing, however, one may question the authenticity of this page, which is not signed with Chopin's usual monogram," notes the professor emeritus at the University of Geneva. “Is this a complete piece or a fragment?” wonders the Swiss musicologist before providing some answers: “Within such a brief span, the contrast and shift in character between the initial eight stormy, passionate bars and the following sixteen, which resemble a pleasant waltz-mazurka, is surprising.”

If not a fragment, could it be an abandoned draft? “The text's state barely aligns with the formal rules of the waltz genre (except for the use of symmetry),” he asserts categorically. The specialist, who is also a juror at the International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw, explains that the composer himself paid great attention to distinguishing his works intended for publication from the album leaves he annotated for friends and admirers. “As it stands, this text hardly qualifies even as a finished miniature,” he says with conviction, adding that the specialists' hypotheses are likely to yield varied interpretations. Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger concludes, “The media exaggerates the significance of this discovery—interesting, certainly, but not groundbreaking enough to alter our perception of Chopin.”

Comments