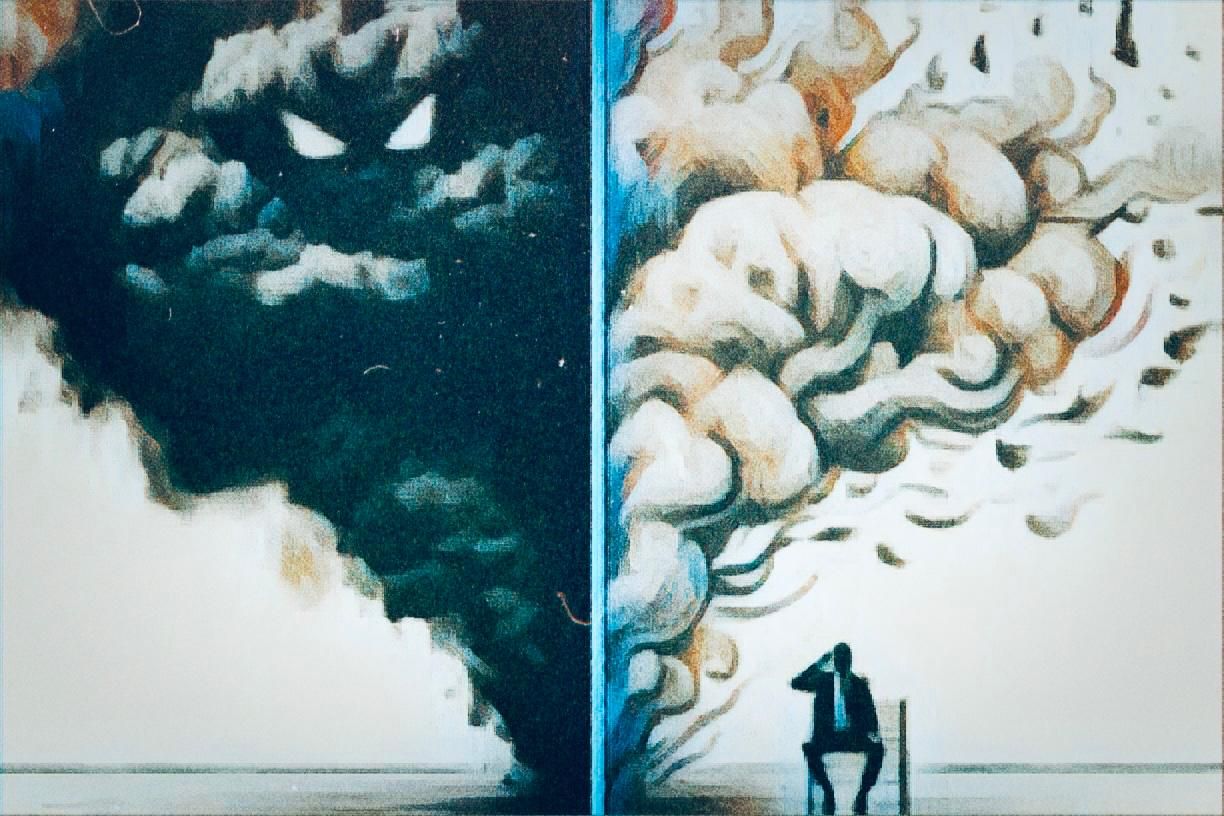

In these times of violence and war, psychological trauma is rampant. Attacks, armed conflicts... Deeply wounded, victims see their lives shattered. Through the lens of psychoanalysis, we will explore various facets of their ordeal and the paths to possible reconstruction.

As we wrote in our previous article, trauma causes a psychic collapse, a shock that leaves a person unsteady, defenseless against the seismic breach and the abrupt rupture in their sense of continuity of existence.

Lebanese people have been living for far too long in a trauma-inducing environment. The repeated situations of hot and cold wars, severe financial and social upheavals, the collapse of their economic resources, the daily confrontation with personal or collective disasters from which they must extricate themselves alone, the constant feelings of anxiety and insecurity, and the recurrence of armed conflicts between factions—all these causes, among many others too numerous to list, are no less destabilizing and can only lead to significant psychosomatic disorders that persist long after the events. Numerous studies show that these traumas are massive and persist over time: data reveal that a large majority of the population exhibits symptoms of post-traumatic sequelae. Chronic anxiety, hypervigilance, recurring nightmares, and depression are very common, hindering their emotional life, social relationships, and professional activity.

Following the 2020 port explosion, many still describe today a state of psychic death, a feeling of unreality, as if a part of themselves had remained frozen in horror. Others are haunted by intrusive memories, involuntarily plunged back into the chaos of the explosions. The psychological impact of trauma unfolds over generations. Post-traumatic sequelae invade relational and family life: confusion in reference points, generalized anxiety, and loss of a sense of belonging undermine bonds.

Lebanese children are particularly vulnerable. According to UNICEF, more than half of Lebanese children show signs of psychological distress related to conflicts. The abundance of information and images conveyed by the media exposes them to a harsh reality made of massive destruction, apocalyptic visions of entire buildings collapsing, and lifeless or bloodied bodies. Today, relentless bombings, civilian massacres, and forced exoduses leave indelible traces on their psyche. This has led to the emergence of major symptoms: night terrors, incontinence, agitation, social withdrawal, chronic anxiety, and difficulties using their intellectual capacities. Their ego is weakened, and family ties struggle to provide security, as their parents are just as helpless, unable to hide their own insecurities.

Many Lebanese describe a feeling of unreality, of depersonalization, as if events were unfolding behind a screen. Others are overwhelmed by traumatic flashbacks, intrusive images that thrust them back into the terror of bombings. Beyond those directly exposed to violence, the entire Lebanese society is affected by the traumas of war. The psychic wounds are inscribed in a painful collective memory. The unprocessed traumas of ancestors resurface in descendants, binding them to a deadly cycle of repetition.

Despite this very concerning clinical picture, a large part of the Lebanese population continues to pursue a life that strives to maintain an appearance of normality. And when some are questioned about the effects of war and its traumatic consequences on their psyche, they respond that they “manage with it.”

Can one really “manage with it”? Can one live with one’s traumas?

Among the many defense mechanisms that play a crucial role in how an individual reacts to traumatic experiences, there are two that could offer us an answer: denial and splitting.

Denial involves refusing to recognize, often unconsciously, a traumatic reality and its unbearable somatopsychic effects. Thus, a person may mention various reasons to justify their discomfort or the nightmares that haunt them, without linking them to the shock they endured.

Splitting involves dividing experiences into distinct compartments. This allows a person to maintain contradictory situations without processing them. As such, they may separate traumatic experiences from their daily consciousness, persuading themselves to function normally, even at the cost of difficulties establishing a coherent perception of self and the world.

Although these mechanisms provide a form of short-term psychic protection, they can make long-term healing much more complex. Numerous studies indicate that traumatic consequences can sometimes persist for an entire lifetime if nothing is undertaken to free the victims.

Here are a few symptoms observed in some traumatized individuals in Lebanon:

- A recurrent repetition of traumatic events keeps symptoms active, such as nightmares, phobias, or psychosomatic disorders. Traumas remain in the background, ready to resurface.

- Disruption of interpersonal bonds, making relationships more difficult by maintaining a state of mistrust and social withdrawal.

- Persistence of chronic somatic issues, such as headaches, nervous tension, and heightened reactivity to anything that may evoke fear or anxiety, thereby prolonging the trauma’s impact on both body and mind.

- Prolonged suffering in the form of feelings of despair, discouragement, and helplessness.

Nevertheless, while trauma leaves indelible marks, it does not entirely define a person’s destiny—provided they are not reduced to their status as traumatized but are recognized for their living spirit, however fragile it may be. This is demonstrated by the singular paths of many victims who invent new forms of engagement and resistance.

For these individuals, spaces must be offered where they can voice their distress, allowing for potential avenues of release. The challenge lies in reactivating the processes of symbolization paralyzed by trauma and enabling the resumption of psychic connection activity.

Thus, analytical work aims to reintegrate traumatic experiences into a narrative framework, giving them a shareable meaning. It involves helping the individual to reclaim their history, however shattered it may be, and to re-engage their creative resources. By restoring a sense of continuity and identity coherence and reigniting desire-driven dynamics, new pathways in life can open.

But this return to life is only possible if there is societal recognition of the traumas suffered. Hence the importance of a process of memory and justice, to acknowledge the victims as whole individuals. This is the essence of a “trauma clinic,” combining the individual approach with consideration of the social and political context.

Comments