- Home

- Middle East

- Turkey Eyeing BRICS Membership While Staying in NATO

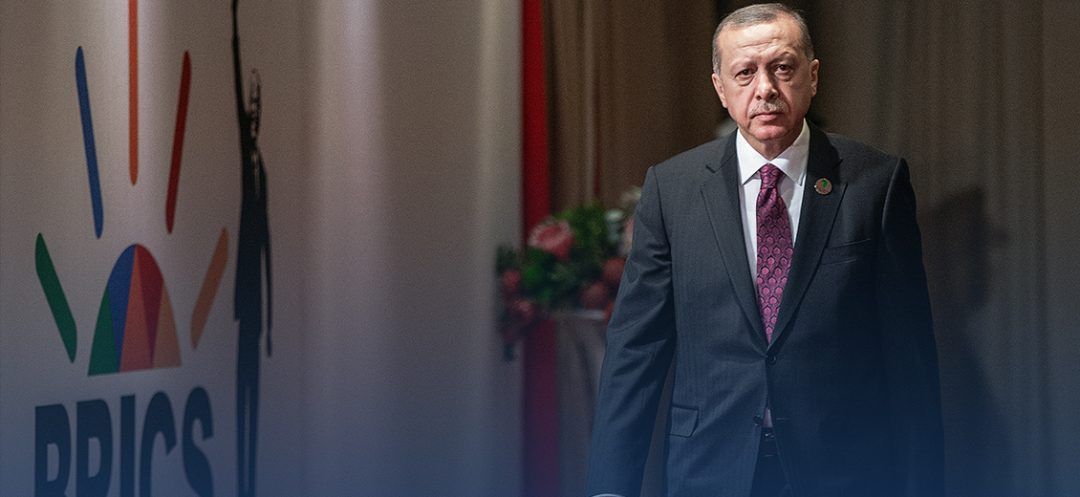

Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan. ©Gianluigi Guercia / POOL / AFP

Turkey's overtures towards BRICS may be a first for a NATO member, but experts say the move is economically driven and aligns with Ankara's desire for "strategic autonomy."

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan will join the BRICS summit in the Russian city of Kazan on Wednesday at the invitation of his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin. He will meet with the leaders of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

Turkey announced last month that it had requested to join the group of emerging market nations. If admitted, it would be the first NATO member in a bloc that sees itself as a counterweight to Western powers.

Most of its members are sharply at odds with the West over the ongoing conflict in the Middle East, and, in the cases of Beijing and Moscow, also its stance on the Ukraine war.

However, experts say Turkey's bid to join does not mean it will turn its back on the West or Ukraine, whose top diplomat visited Ankara on Monday — let alone NATO.

“The government is continuing to deepen its ties with countries that are not members of the Western alliance, in line with the strategic autonomy that Turkey is pursuing,” said Sinan Ulgen, a researcher at the Carnegie Europe think tank, in an interview with AFP.

“But the initiative is also partly economic: it’s expected to have a positive impact on bilateral economic relations.”

“A multipolar asymmetric world”

The BRICS nations represent just under half of the world's population and around a third of global gross domestic product.

As a “platform,” BRICS does not impose binding economic obligations on its members as the European Union does, at whose door Ankara has been knocking since 1999.

Erdogan raised a similar point last month. “Those who say ‘don’t join BRICS’ are the same people who have kept Turkey waiting at the EU’s door for years,” he said.

“We cannot cut ties with the Turkic and Islamic world just because we are a NATO country: BRICS and ASEAN are structures that offer us opportunities to develop economic cooperation,” he added.

Ulgen noted that the two issues are connected.

“Turkey would not have taken these steps towards BRICS if it had been able to pursue integration talks with Europe, or even upgrade the customs union,” which has been stalled since 1996.

Soli Ozel, an international relations professor at Istanbul's Kadir Has University, said Turkey is responding to an anticipated shift in the global center of gravity.

“The Turkish government sees that the unquestioned hegemony of the West cannot continue as it is,” he told AFP.

“And like many other countries, it is trying to position itself to have more of a say if a new order emerges in an asymmetrically multipolar world.”

At the same time, Ankara wants to take advantage of the “weakening” of Western influence, particularly that of the United States, to create more room for maneuver.

However, Turkey remains part of "the security-conscious West," and its economy certainly remains linked to the European economy, he added.

For Gokul Sahni, a Singapore-based analyst, Ankara aims to achieve the best of both worlds.

“Turkey wants to benefit from being West-adjacent, but — knowing it can't ever fully become part of the West — it seeks to partner closely with the non-Western BRICS countries,” he told AFP.

And it is a low-risk gamble because joining BRICS "has no security implications," he said.

“Turkey will never leave NATO,” said Ozel, but its rapprochement with BRICS reflects “the need for change and the desire to obtain more from emerging regional powers.”

— Anne Chaon, with AFP

Read more

Comments