In these times of violence and war, psychological trauma is rampant. Attacks, armed conflicts... Deeply wounded, victims see their lives shattered. Through the lens of psychoanalysis, we will explore various facets of their ordeal and the paths to possible reconstruction.

Simon Fieschi, former webmaster of the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, was found dead on Thursday, October 17, 2024. The causes of his death remain unknown. He had been critically injured during the attack on January 7, 2015, in Paris.

His death brings back into focus the heavy psychological toll paid by survivors of attacks or wars, as Simon Fieschi’s fate echoes that of many other survivors, most of whom remain largely unknown to us, yet who continue to live with the ravages of trauma, true psychological earthquakes whose aftershocks can shake an entire lifetime.

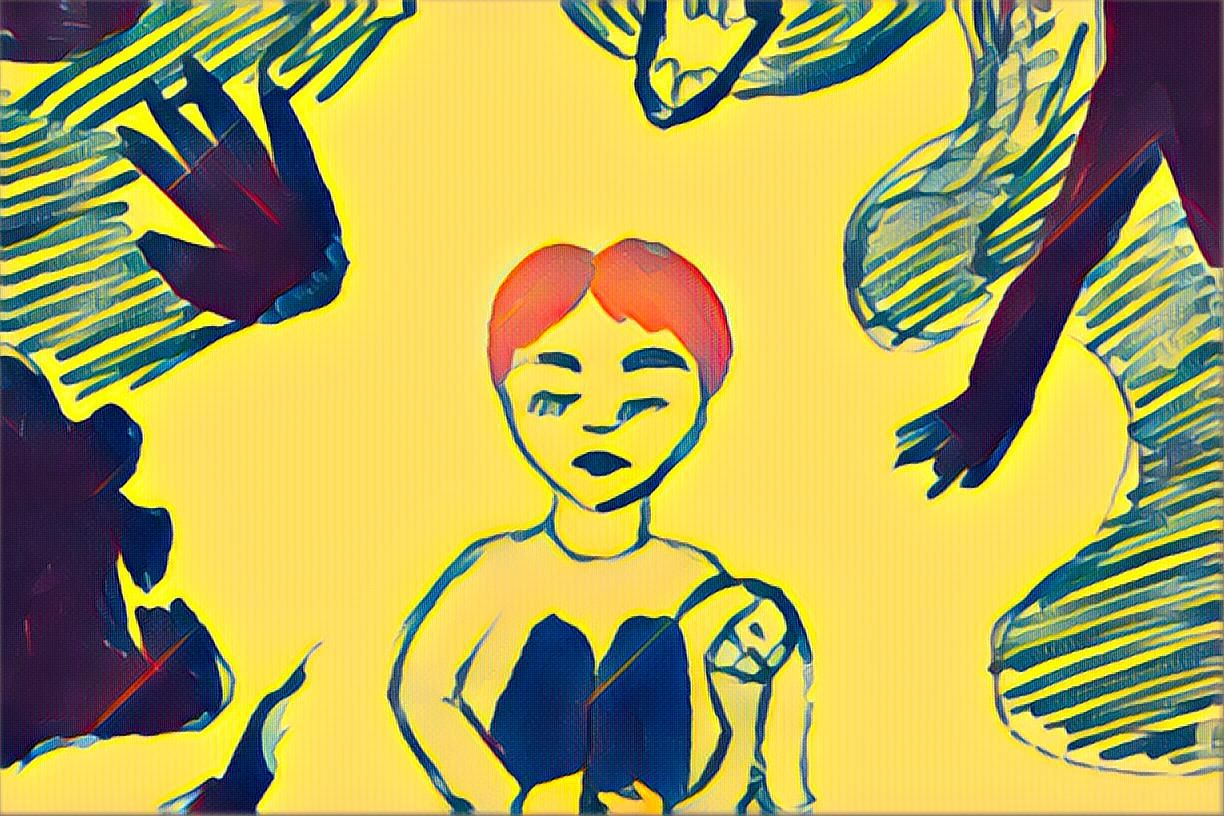

Behind the unique circumstances of each survivor’s journey lies a shared silent suffering, the same shadow cast by the traumatic event. These broken lives remind us of the persistence of trauma and its devastating long-term effects. Beyond physical scars, it is primarily in the psyche that these survivors have been deeply wounded, some describing an “absolute upheaval” and an “inner cataclysm.” Haunted by the memory of friends or family members, injured or killed before their eyes, tormented by survivor’s guilt, they speak of sleep filled with nightmares, anxiety attacks, and various phobias. However, it must be noted that the repetitive reliving of traumatic scenes is not merely destructive. It is also a desperate attempt to master the experience, to become the agent of it rather than just the passive object. An effort to give meaning and words to an unspeakable experience, as evidenced by the survivors’ testimonies.

These severe post-traumatic symptoms undermine the personal, professional, and social lives of survivors. Some fail to reconnect with their previous existence: withdrawn into themselves, overwhelmed by dark thoughts, they gradually lose their footing before finally succumbing.

In psychoanalysis, trauma is central to the theory of neuroses. Freud defines it as a “surge of excitations” which, due to its intensity, breaches the defenses against intrusive excitement, overwhelming the capacity for integration and symbolization. It is a veritable “internal foreign body,” impossible to assimilate, which relentlessly resurfaces in waking or sleeping flashbacks. Victims’ efforts to suppress or deny traumatic memories to avoid the pain often lead to the development of symptoms such as nightmares, flashbacks, and hypervigilance. Trauma introduces a specific temporality, the one of “afterwardness.” The event may not appear traumatic at the time, but it becomes so later when it links to unconscious representations and reactivates earlier conflicts. This explains the often observed gap between the apparent banality of an event and its devastating psychological consequences.

Sándor Ferenczi originated the concept of “psychic shock,” triggered by an unforeseen event, a jolt that leaves the ego stunned, split, as if dead. The narcissistic wounds are gaping, the identity shattered.

For D.W. Winnicott, trauma confronts the subject with a “fear of collapse,” the dread of a return of what has already happened, plunging the subject into an experience of primitive agony and annihilation.

For Jacques Lacan, the victim is thrown into “traumatism,” a psychic death experience that defies all symbolization. The traumatized subject appears frozen in time, petrified in the terror of the tragic moment. Trauma confronts a reality that is impossible to articulate, beyond meaning and words. The subject grapples with intense and contradictory emotions—terror, shame, guilt, anger—which they cannot attach to representations.

Trauma also shakes the foundations of identity and the core beliefs that give life meaning. The illusion of invulnerability or the denial of mortality shatters, along with the trust in a world perceived as generally safe and coherent. The traumatic breach exposes the arbitrariness, senselessness, and fragility of everything. Hence, an intense sense of insecurity and distrust invades the victims. The world becomes threatening, unpredictable. Others may be seen as potentially dangerous, malevolent. The subject isolates, withdraws, while remaining in a state of constant alert, jumping at every loud noise, panicking at the thought of a possible repeat of the tragedy. Phobic avoidance is part of post-traumatic symptoms, alongside intrusive flashbacks. These are all warning signs that should alert those close to these individuals to their psychic distress.

But there are other signs, more subtle yet equally telling. Depressive disorders, first of all, with their burden of sadness, lack of motivation and inability to take pleasure, psychomotor slowdown, and dark thoughts. This suffering reflects the impossible mourning of the lost ones but also the loss of a part of oneself, dead with the event.

Self-medication and addictive behaviors also emerge, desperate attempts to numb intolerable psychic pain. Alcohol, drugs, medication… crutches to keep unbearable images and emotions at bay.

For some, the most concerning sign to watch for is the emergence of suicidal thoughts, a temptation to end a life drained of meaning and tormented by nameless suffering.

Because beyond the trauma itself, the entire dynamic of life is altered. Relationships with others are damaged, previous investments (work, leisure, projects) lose their flavor, their reason for being. The future seems closed off, reduced to a dull and painful repetition.

Faced with this severe clinical picture, long-term therapeutic care is essential. It may combine various approaches. The goal is to allow the gradual resumption of psychic life, to restart the processes of symbolization and subjectivation that were halted by the traumatic breach.

This is why therapy must (re)build a space where speech can emerge, where these emotions can be named, expressed, shared. The psychoanalytic setting provides a place of attentive and compassionate listening, where words can be spoken, no matter how fragmented or painful. The goal is to welcome traumatic flashbacks, without forcing them but also without fleeing from them, in order to gradually integrate them into a narrative, to weave them into shareable representations.

At the same time, a linking process must begin, attempting to metabolize the overwhelming emotions and inscribe them into shareable representations: repetitive nightmares, disturbing bodily sensations, and unspeakable anxieties are all elements to be reworked, elaborated, symbolized.

This is how we can support the subject’s creative resources, their attempts to give form and meaning to the traumatic experience. Writing, drawing, speaking, role-playing, bodily expression—any means is valid to try to contain the terror, to give it a human face.

Another challenge is to assist in the work of mourning, that always unique journey of separating from the lost object without losing oneself. Mourning for lost loved ones, but also for a part of oneself that died in the tragedy, and for a world that, for some, is forever lost. A long and painful process, filled with back-and-forth, chaotic moments, and gradual relief.

But this reconstruction is an uphill path, always threatened by the return of the same and the temptation of oblivion. Depressive or addictive relapses are common, and suicidal impulses can sometimes be devastating. This is why long-term support is crucial, capable of negotiating with the time of trauma, without rushing it but also without allowing it to stagnate.

The essential goal of therapy is, ultimately, to rekindle the movement of life, desire, and trust in the future. To rediscover the taste for things, the joy of relationships, the excitement of projects… A whole process of reinvesting in life, so that the future once again becomes desirable and livable.

The fates of survivors of attacks or wars remind us of the fragility of psychic life in the face of historical upheavals. They underscore the absolute necessity for collective mobilization and cultural work in response to horror. For this is indeed a battle, a battle for life to triumph over the forces of death and destruction.

In these troubled times, psychoanalysis has more than ever its place to think through these extreme situations and offer spaces for speech and elaboration. Not as an all-powerful knowledge, but as a precious compass to navigate through the darkness of trauma. With the hope, always, that a day will come when life will have the final word.

Comments