Every week, we invite you to explore a striking theme to reveal its depth and richness. These lapidary, often provocative formulas open up new perspectives on the intricacies of the human psyche. By deciphering these quotes with rigor and pedagogy, we invite you on a fascinating journey to the heart of psychoanalytic thought to better understand our desires, anxieties and relationships with others. Ready to dive into the deep waters of the unconscious?

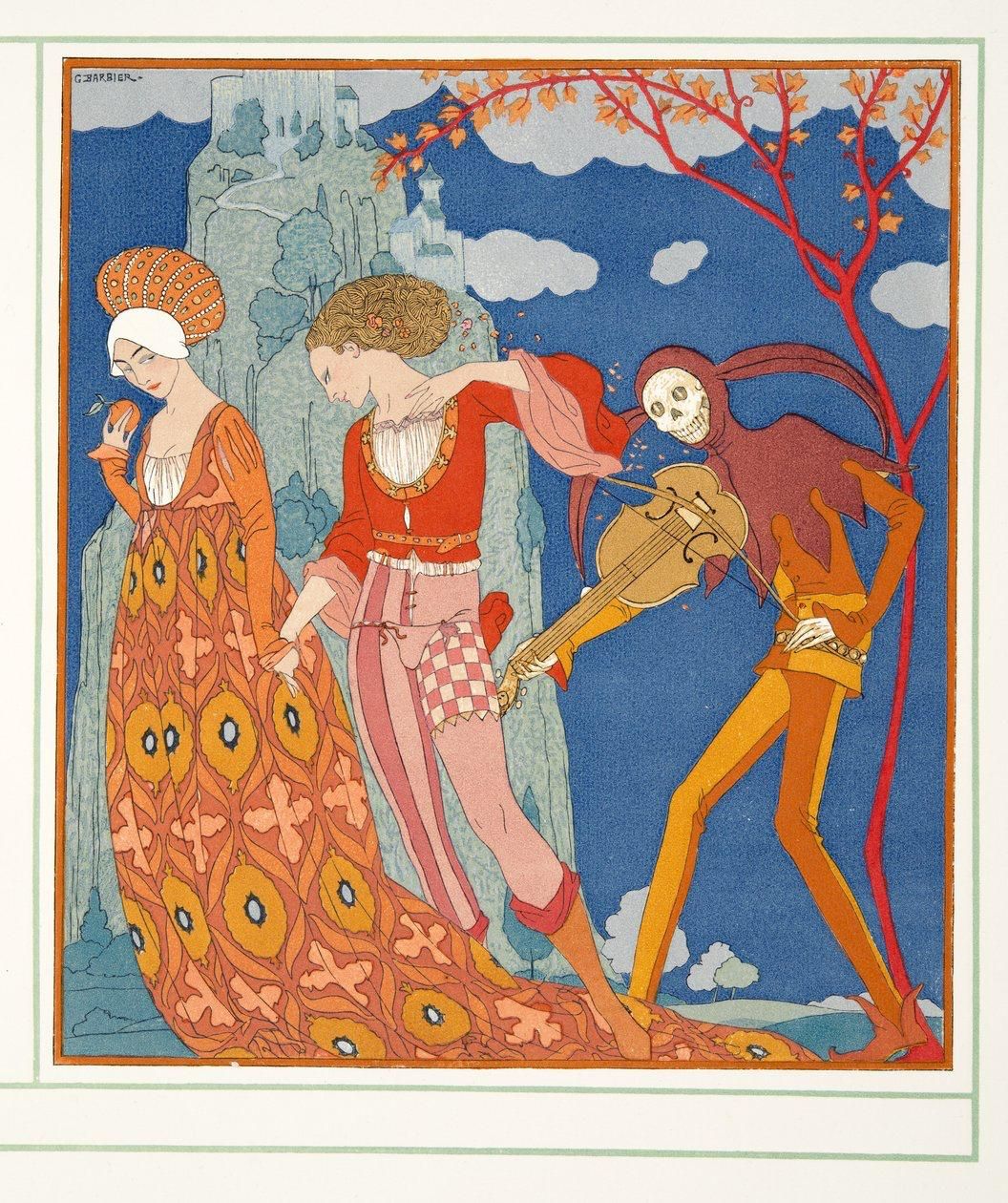

“The function of desire must remain in a fundamental relationship with death.” – J. Lacan

Desire is always born from a lack, from an absence. It expresses the nostalgia for a lost wholeness, for an original state of satisfaction that we seek to rediscover throughout our lives. Yet, this desire is insatiable by nature, as its object is always substitutive, always misaligned with the fundamental lack that defines us.

In his quotation, Lacan inextricably links desire to death, the latter being deeply rooted in the human condition. Although desire is a relentless pursuit that can never be fully satisfied, it is what humanizes us, what pulls us out of the state of nature and introduces us into the symbolic world, the world of language. In doing so, desire also confronts us, inevitably, with finitude and symbolic castration. For in order to access language and culture, we must renounce absolute enjoyment, internalizing the law of prohibition and loss. This is how the intimate bond between desire and death is woven, because desire is always a desire for recognition. It brings us face to face with our incompleteness, our fundamental dependence on the other. It reveals our vulnerability, our “being-toward-death” (Heidegger). In this sense, death is not just our biological end but the absolute limit of our being, something that escapes all control, all possibility of symbolization.

In our cultures, speaking of death is often a blind spot. For some, it is a taboo; for others, a matter of superstition, as if mentioning it would make it too present.

Consider the example of a child between the ages of 6 and 8 who asks their parents about death. Their reaction often reveals discomfort and embarrassment, unaware that the child, with their sensitivity and intuition, has a keen sense of finitude and desires truthful answers about death, illness, and aging. Too often, however, adults evade these questions, perhaps because they themselves dare not confront them, using the excuse of wanting to protect the supposed innocence of children.

In reality, behind this difficulty in talking about death often lies our own difficulty in accepting it, our own adult anxiety about the idea of our disappearance. In a society that values youth, performance, control, and frenetic consumption, alongside obsessive positive thinking and addiction, death appears as a scandal, an event to be buried in the darkness of our consciousness. Otherwise, it risks awakening our own ghosts, forcing us to face our own fears.

Nevertheless, it is crucial to accompany children when they ask about mortality, to help them come to terms with this fundamental reality of existence, without false reassurances. Not to frighten or depress them, but to allow them to integrate death into their worldview, to give it meaning. By talking about death, by putting it into words, we can make it less terrifying. But this requires us to come to terms with our own finality. We can only guide our children on this topic if we ourselves engage in this inner journey, in this quest for clarity and acceptance.

Becoming a parent means accepting that giving life comes with the knowledge that the being we bring into the world will escape us, that they are destined to leave us. It is consenting to this movement of life that constantly surpasses us, tears us away from ourselves, and opens us to otherness. It is showing them, by example, that it is possible to live fully while making room for death, for absence, for the lack inherent in all existence.

Perhaps this is, ultimately, the task incumbent on every human being, whether they are a parent, educator, or ordinary individual: not to transmit ready-made answers but to accompany those who ask questions on their journey toward their own truth. In doing so, we may contribute modestly to ensuring that life, despite death, remains an adventure worth living, as well as to understanding the richness of a question that would be better left open and fertile.

This dialectic between desire and death is reflected in the psychoanalytic process when a subject reaches the crossing of anxiety and fantasies. This is reminiscent of the absolute helplessness of the infant. This journey will never be easy and will encounter many resistances, beginning with those found in the infantile relationship to parents. The subject will need to gradually relinquish alienating identifications, question their certainties and illusions. However, this journey is absolutely necessary if the subject wishes to achieve a freer, more subjective, and more creative desire. It will be a work of mourning and renunciation that leads to a symbolic death, the renunciation of omnipotence, the acceptance of symbolic castration, that is, the law of lack and mortality.

Understanding the link between desire and death should not, however, be morbid or depressing. On the contrary, discovering this truth is liberating. This is the meaning of Montaigne’s quote in his Essays : “The premeditation of death is premeditation of freedom. Knowing how to die frees us from all subjection and constraint.” Indeed, it is precisely because we are finite beings that our desire takes on all its intensity and urgency. Lacan reminds us of the necessity of not giving up on our desire, which can never be reduced to an object or materiality. It is because absolute enjoyment is forbidden to us, because we constantly stumble upon the Real of our finitude, that desire is continually reborn from its ashes. The presence of death as an integral part of life can enrich our daily experiences and give deeper meaning to the quest for desire.

German composer Kurt Weill created a musical work titled Youkali. Set to the rhythm of a tango-habanera, it evokes an imaginary island, a place of dreams and desire where all worries disappear, and happiness is omnipresent. It serves as a magnificent metaphor for the human condition, illustrating a utopia that inhabits and torments us.

Here is an excerpt from the beginning of the song:

“Youkali, it’s the land of our desires,

Youkali, it’s happiness, it’s pleasure.

Youkali, it’s the land where all worries vanish.

It’s like a clearing in our night,

The star we follow, it’s Youkali.”

But the melancholic and captivating melody reminds us, in the end, that Youkali is only an illusion, the dream of an unfulfilled and nostalgic desire:

“Youkali, it’s the land of our desires,

Youkali, it’s happiness, it’s pleasure.

But it’s a dream, it’s madness,

There is no Youkali.

But it’s a dream, it’s madness,

There is no Youkali.”

It would certainly be equally utopian to believe that one day, there will be leaders in the world, especially among those in our region, who would humbly grasp the representation of their mortal human condition, and that they could then demonstrate more wisdom and humanity in the exercise of their functions.

Comments