Gilbert Amy notes that the contemporary era is marked by a perpetual change in musical principles, influenced by technology and media, while asserting that artificial intelligence will never replace the human essence of musical art.

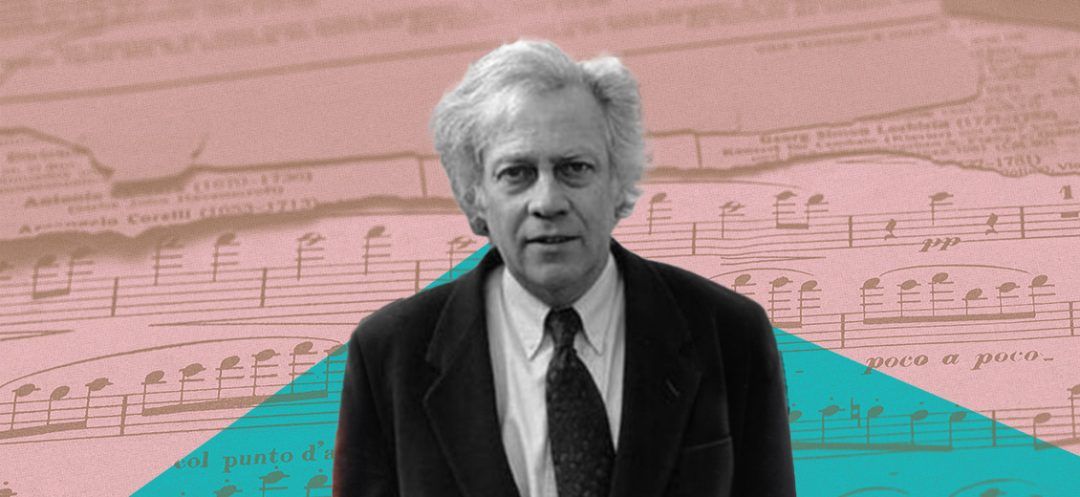

The Turbulent Infinite. A nickname evoking the vigor and uncompromising nature of a composer for whom music was never a mere predefined language but a material to be shaped, reshaped and even thoroughly upheaved. This was how Gilbert Amy was dubbed at a conference organized in 2016 by the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Lyon, where he was the director from 1984 to 2000. Today, in the dim light of his office, his silhouette slightly bent under the weight of years, he retrieves a volume from a cluttered shelf, his fingers brushing the dusty binding. It is Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. A faint, almost imperceptible smile crosses his lips. The man who had vehemently opposed tonal music throughout his life now confesses, in the calm of his reflections, that time has dulled his former certainties. The fire of youth, which once rejected all compromise, has transformed into a softer flame, less sharp, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of what he had so ardently fought against.

New Music

After flipping through the pages of the Beethoven score and commenting on the work’s subtleties, Gilbert Amy rises and moves towards the piano. His fingers initially glide over the keys, playing a few scales with natural ease, before being carried away by the first notes of a Chopin prelude. This piece inevitably reminds him of Yvonne Loriod, the wife of the illustrious Olivier Messiaen, who decades ago had instilled in him the art of pianistic interpretation. “Chopin is a treasure trove of harmonic refinement and finesse in pianistic writing,” the composer asserts after finishing the last chord. Despite his current openness to tonal art music—dominant in Europe from the late 17th century to the mid-20th century—Gilbert Amy remains a defender, even a pioneer, of atonal music. This refers to the new Western art music of the post-modern era, from the second half of the 20th century onward.

Post-Post-Modern Era

“The post-modern era is already outdated. We are now in the post-post-modern era. In the 1950s and 60s, musical language was in formation, and it had nothing to do with tonality. However, there were also deviations, such as the chance music represented by John Cage, which introduced randomness into music,” explains the octogenarian artist. According to him, there were musicians who believed in precise writing and fixed notes, following very specific patterns, and on the other hand, those who sought to deconstruct this, notably Cage, by “letting anything replace language,” thus creating a form of generalized improvisation. “Today, we live in an extremely different situation, as we are evolving in an increasingly individualized world, especially in the West, where every individual wants to be a cosmos,” continues Gilbert Amy, noting that this trend affects composers as well as painters and architects. He adds, “It is no longer so much the movements that matter, but rather the individuals who manipulate the elements. At 88, having lived several lives in a way, I observe that in the past, there were models to follow and realities to construct. Nowadays, creators evolve according to their own vision, without conforming to precise criteria.”

Mobility of Principles

The influence of media has also played a significant role in the evolution of what will be called the music industry. “Organizations like the Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music (IRCAM) have also been created to transform sound, to generate it through machines and calculations— a perspective already anticipated by visionary musicians like Iannis Xenakis,” notes the composer, who also had a distinguished career as a conductor. “We then found ourselves faced with a kind of constant mobility of principles. We no longer felt on a guiding line; we had the impression of having to be an individual among others, more or less creative,” he emphasizes.

Regarding the reduction of the entire musical hierarchy to the scale of sound, the artist is categorical. “A composer worthy of the name aims to create a work with a capital W, through individual pieces that represent advancements, styles and varied instrumentations. However, ultimately, these individual contributions come together to form a coherent work,” he explains. Gilbert Amy, who was made a Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters in 2013, strongly disputes the idea that all sounds are equal. This opinion clashes with John Cage’s perspective, who, with his concept of chance music, believed that a C note in itself had no particular value, being just as good as a B or an F sharp. “This is obviously contrary to all the musical education we received: ear training, which precisely considers that music worthy of mention is that which is organized, heard, logical and shaped by centuries of writing,” he adds.

Artificial Intelligence

Gilbert Amy observes that some contemporary approaches seem to turn their back on the search for musical language. Added to this is another disruptive element: the introduction of technology. He expresses his doubts with conviction: “I believe that artificial intelligence applied to music is a dead end. Although algorithms can imitate human intelligence and produce plausible results, they will never create a true work of art. An algorithm cannot paint a picture or compose music with human essence. I do not believe it. In creative terms, there remains this purely anthropological spark that we call music, and no machine can replace it.” The French master had interacted with great composers, including Igor Stravinsky, to whom he dedicated a work for voice and orchestra in 1966 titled Strophe. Might he be reassured by the evolution of musical art? “That is a question that does not concern me, as human life comes to an end one day. We then become active witnesses of an era. Frankly, I have no idea what music will become in the future. I must admit that it is a problem I cannot solve,” he replies, drawing his final point.

[readmore url="https://thisisbeirut.com.lb/culture/288231"]

Read more

Comments