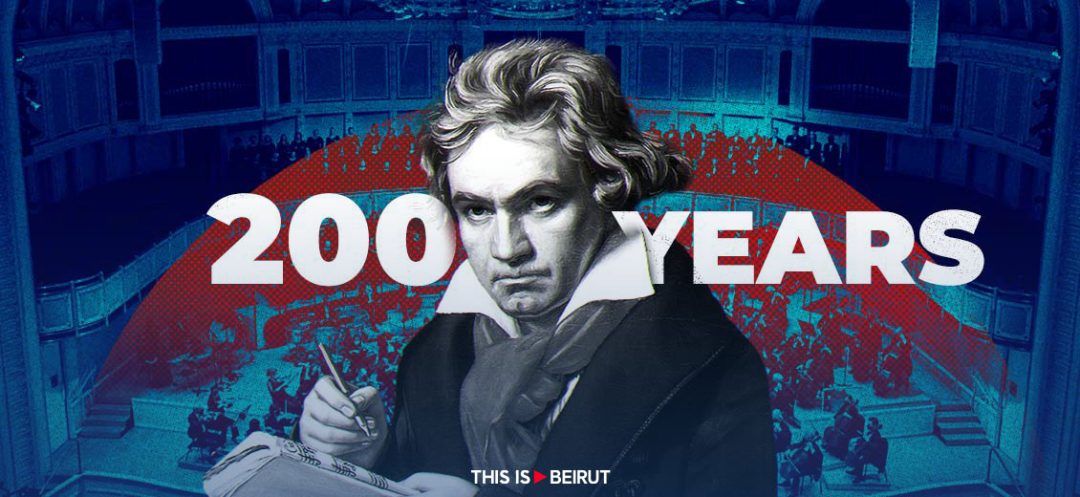

The classical music scene commemorates, on this May 7th, the bicentennial of two immortal works by Ludwig van Beethoven: the Missa Solemnis and the Ninth Symphony. In a world torn by bloody conflicts, this celebration offers an opportunity to reflect more deeply on the ideal of universal brotherhood instilled by the genius from Bonn.

In 2020, the classical music scene was preparing to pay tribute and honor to one of the most eminent thinkers of music of all time, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), on the 250th anniversary of his birth. However, fate decided otherwise. Unfortunately, the festivities collided head-on with unforeseen health circumstances, the mere mention of which still evokes bitter memories. The plethora of concerts planned to honor the greatness of this demigod was postponed, canceled, or reduced to insipid reflections of their hoped-for splendor. Today, four years have passed, and yet the situation remains just as bleak. The lingering shadow of devastating conflicts that plague our world continues to spread. In this context of uncertainty and turmoil, the musical world is nevertheless poised to rise to new heights and to commemorate, in all its majesty, the bicentennial of the creation of two immortal masterpieces by the genius from Bonn: the Missa Solemnis (April 7, 1824 in St. Petersburg and May 7, 1824 in Vienna) and the Ninth Symphony in D minor (May 7, 1824 in Vienna).

Desire for eternity

"The Missa Solemnis carries the essential spiritual message of Beethoven, turned, on one hand, towards God and transcendence and, on the other hand, towards a fraternal humanity for which he seeks redemption and peace, with, moreover, an underlying desire for eternity," explains Bernard Fournier, a great expert on the work of the German master, to This Is Beirut. Before embarking on the actual composition of his Grand Mass op. 123, which he then considered "his greatest work," Beethoven extensively researched the history and sources of the Catholic Mass liturgy. He was, in fact, very close at the time of composition (1818-1823) to the theologian and composer Friedrich August Kanne (1778-1833), author of A History of the Mass. "He then endeavored to give the best expression and a specific musical sense to each verse, sometimes even to certain words of the text based, on one hand, on the conception he had of the liturgy, and on the other hand, on his personal faith largely influenced by his very special relationship with God the Father as well as by his universalist humanism imbued with the Enlightenment philosophy and that of Kant," specifies the French musicologist.

Powerful architecture

The Missa Solemnis is characterized, according to Fournier, by an "architecture of exceptional power," conceived with an unprecedented concern for unity: the unity of each of the five movements setting to music each of the five great hymns of the mass, the unity of the mass as a whole both from a musical point of view – the entire mass unfolds from a germinal motif, that of eleison, given at the beginning of the Kyrie – and from a spiritual point of view. "From the beginning to the end of the mass, Beethoven particularly focuses on words belonging, on one hand, to the paradigm of sin and deprecation (peccata, peccatorum, eleison) and, on the other hand, to that of the all-powerfulness (omnipotens, omnipotentem) of this God also 'omniscient and eternal'," emphasizes the expert. He adds that this conceptual duality is musically translated into a dialectic between fourth intervals, representing man, and third intervals, symbol of God. Furthermore, another unprecedented arrangement, this mass is conceived as a multifaceted dialogue between "the sinful but willing man" and "the merciful but all-powerful and possibly terrifying God." It is a dialogue between the heavenly sphere and the human sphere.

After the Missa Solemnis comes the Ninth Symphony and Beethoven's last quartets. "This triptych constitutes the quintessence of the late Beethoven's musical expression of spirituality, dominated by the Dankgesang of the Quartet opus 132 and the Grand Mass," concludes Fournier. It is worth mentioning that the musicologist has just published a book, titled La Missa Solemnis de Beethoven, Immanence et transcendence, published by the Institut du Tout-Monde editions, in which he scrupulously analyzes the famous Mass in D major.

A song to humanity

Beethoven's Ninth Symphony stands out as the absolute jewel of his musical corpus. Although other compositions such as the Missa Solemnis, the Diabelli Variations, the last five piano sonatas (op. 101, 106, 109, 110, and 111), and even – and especially – the last five string quartets (op. 127, 130, 131, 132, and 135) and the Great Fugue (op. 133) may be considered by experts as "greater masterpieces" strictly on a musical level, the Symphony in D minor remains Beethoven's spiritual testament, his song of universal brotherhood to humanity. That said, what particular traits give this monumental work its distinctive character? "The main elements are perhaps the combination of the sophistication and ingenuity of the musical techniques with the persistent strength and depth of the emotion – the intensity of the first movement, the energy of the second, the sheer beauty of the third, and above all the exuberance of the finale," responds Barry Cooper, eminent Beethoven scholar and editor of The Beethoven Compendium. And he adds, "This combination is coupled with a sense of progress and development through the work, from darkness to light, from minor to major, from despair to joy, which provides an uplifting overall coherence."

New musical paradigms

Beethoven's Ninth Symphony constitutes the first example of a symphony integrating the human voice into its famous Ode to Joy, a revolutionary innovation that would soon be adopted in Felix Mendelssohn's Symphony No. 2 in B-flat major (1838-1840), but would only be fully explored more than seventy years later by Gustav Mahler in his Symphony No. 3 in D minor (1895-1896). "Beethoven’s establishment of new musical paradigms started long before his Ninth Symphony, and his successors held up his major works as models in demonstrating that compositions and particularly instrumental music could function as great art destined for posterity, on par with grand paintings or epic poetry," remarks the British musicologist. According to him, the Ninth Symphony contributed to consolidating this vision, with its overwhelming grandeur and complexity. "It also demonstrates that voices can be used for expansion of an instrumental work, rather than instruments being used simply as supplement or accompaniment to voices," he adds.

Ode to Joy is the finale of the fourth and final movement of said symphony, where human voices unite in a grand celebration of universal brotherhood, this "kiss to the whole world." The verses, taken from Friedrich Schiller's eponymous poem (1759-1805), illustrate the aspiration to a united humanity, beyond cultural and national divisions, to embrace the joy of shared love. The (somewhat flat) rearrangement of this ode by Herbert von Karajan (1908-1989) would be adopted as the official anthem of the European Union in 1985.

And ten!

As a musicologist, Barry Cooper has dedicated much of his career to studying and demystifying the work of the famous German composer. His in-depth research has shed new light on many aspects of Beethoven's life and music, broadening our understanding of his creative genius and his impact on Western music. He is especially famous for his work on Beethoven's unfinished sketches for the Tenth Symphony, providing valuable insights into the composer's intentions and creative processes. "The false idea of gradual progression misled some into expecting the Tenth to surpass the Ninth, but instead it heads in the opposite direction," he points out. And he concludes, "Instead of embracing the world and even looking ‘beyond the stars,’ it looks inward. By using E flat, the key Beethoven used most often, and C minor, the minor key he used most often, he seems to be presenting himself as the lone artist viewing the contrast between Earth and Heaven."

Read more

Comments