Passed but not carried out in Lebanon since 2004, the death penalty remains stipulated in the Penal Code. Following the recent passing on February 9 of one of France’s foremost advocates for the abolition of the death penalty, Robert Badinter, a former French Minister of Justice, the question of whether to abolish the death penalty resurfaces in Lebanon.

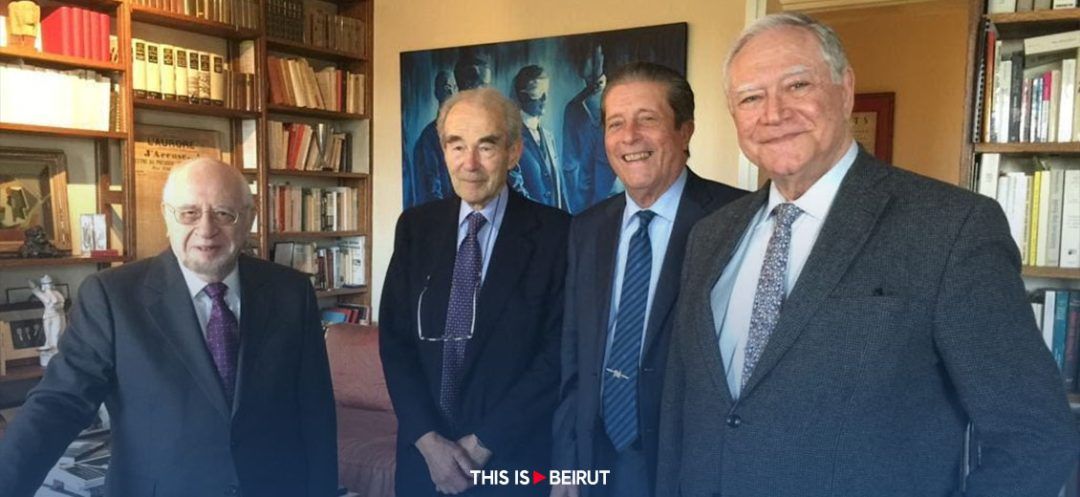

Strongly contested by certain jurists and political figures, the death penalty is a matter of widespread controversy between advocates and opponents of its abolition. Former Minister of Justice Ibrahim Najjar emphasizes that “now is a time for contemplation and reflection.” Najjar is the vice-president of the International Commission against the Death Penalty and had a close relationship with Robert Badinter.

According to him, although still enshrined in legal texts, the death penalty has been practically abolished in Lebanon. “First, it has not been carried out since 2004. Moreover, when we established the Special International Tribunal in response to the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri and his companions in 2005, it was required that the death penalty not be pronounced. In other words, Lebanon has indirectly accepted this abolition,” explains Najjar, a fervent advocate for ending the death penalty.

He recalls that in 2011, Lebanon passed laws allowing for sentence reductions, including for capital punishment. “This means,” he specifies, that “even if judicial decisions impose this penalty, it will never be carried out.”

“It is not to conceal the failure of a state to govern, or its failure to restore order that the death penalty should be maintained,” he insists, considering that “the judge cannot play God by granting or taking away life from individuals, as the right to life should always prevail.”

According to lawyer Nasri Diab, “The main driving force behind the struggle against the death penalty has been the judicial errors committed, long before the issue had a humanitarian dimension.”

He points out that “numerous verdicts have been pronounced sentencing defendants to death, only to later discover their innocence.” Given the irreversible nature of the death penalty, the call for its abolition has grown louder. Another great danger, as Diab explains, “emerges when the sentence is wielded by political regimes, notably the major dictatorships of the 20th century, using it against political opponents under the guise of treason or acts against the State.”

Why has the death penalty not been abolished in Lebanon?

On the national level and from a religious standpoint, Najjar explains that “it is not easy for a Muslim to openly support the abolition of the death penalty. For him, it would mean opposing Islamic doctrine.” Why? He highlights that in Islam, the death penalty applies in two cases: adultery and apostasy (publicly renouncing a doctrine, belief, or religion).

One can envisage legal subterfuges that many Muslim countries, such as Turkey and Malaysia, have adopted. “This involves reducing the death penalty to the payment of material compensation, a method provided for in Islam, and known as ‘diya’ in Arabic,” indicates Najjar.

According to lawyer Diab, the confessional argument is just one among several factors that explain the reluctance of some to abolish the death penalty. He underlines facts related to the crime itself. “Some crimes are so abominable that no prison sentence can adequately sanction them,” he notes, citing the Dutroux case in Belgium as an example. “In this country, renowned for being one of the most peaceful countries, and for having abolished the death penalty for a long time, Marc Dutroux and his spouse Michelle are behind bars for the sequestration, kidnapping, rape, and massacre of minors. So many facts that sparked widespread popular indignation,” he recalls. “At the time, Belgian society considered these individuals as outsiders from the society and therefore not deserving the same legal treatment as ‘ordinary’ criminals,” he adds.

Moreover, despite sentence reductions and the capping of terms, even for hard prison sentences, “any criminal, regardless of the nature of his crime, will eventually regain his freedom, with the potential risk of posing a continued threat to society,” Diab indicates.

A third argument raised by opponents of abolishing the death penalty is the “impossibility for certain criminals to be rehabilitated and reintegrated into society, particularly in cases involving sexual crimes,” the lawyer asserts. These delinquents “declare having uncontrollable impulses and express uncertainty about their ability to control themselves upon release from prison, as evidenced by high rates of recidivism in certain circumstances,” he elaborates.

The fourth consideration relates to economics. According to anonymous sources, “These criminals, for whom the risk of recidivism is almost certain, (in the cases of abominable crimes), will impose colossal financial burdens on the State.”

In Lebanon, the death penalty has become obsolete. Although frequently pronounced, its implementation is rare, and abolishing it requires a parliamentary majority. Does this imply that Lebanon falls short of the principles of freedom and democracy? Is the death penalty ineluctably the sanction of dictatorships and authoritarian regimes? “This is difficult to settle, particularly given that two of the world’s biggest democracies, the US and Japan, continue to uphold it,” concludes Diab.

Read more

Comments