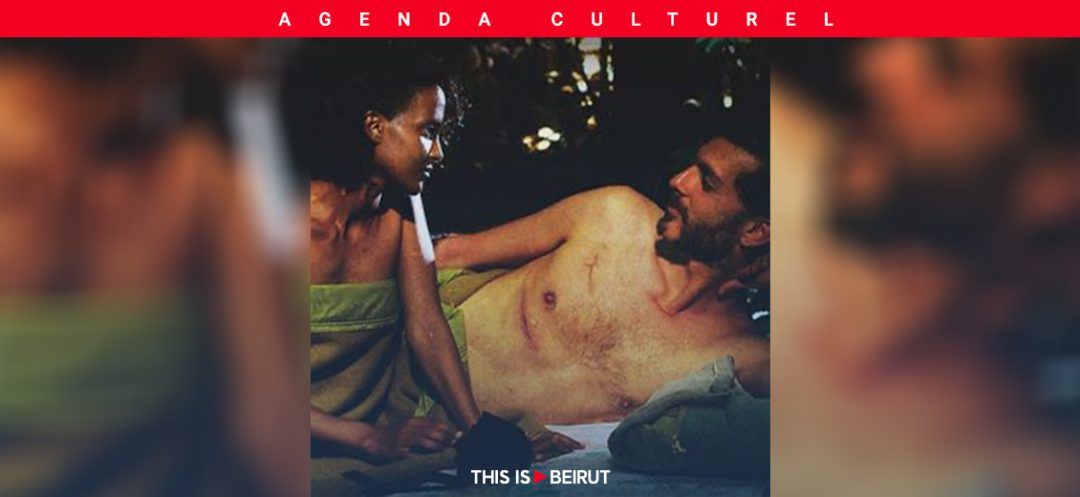

When two outcasts fall in love, their love has the grace of flowers blooming in gutters. On screen, it appears all the more beautiful, as it is contrasted with the surrounding reality. This cruel opposition between pure love and the deficiencies of an environment where all freedom is forbidden is where the sharp and poetic gaze of Wissam Charaf settles in his latest feature film, a tale-like movie, Dirty, Difficult, Dangerous, or in Arabic Hadid, Nhas, Battariat (iron, copper, batteries), in theaters since Thursday, January 11th.

Wissam Charaf chose this translation for the English title because, he says, “In professional jargon, the terms dirty, difficult and dangerous are qualifiers that enter into the classification of professions that are measured in degrees of danger. And here, we are far from the comfort zone.” Indeed, the two protagonists of the film have thankless jobs. Mehdia (Clara Couturet) is an Ethiopian domestic worker, and Ahmed (Ziad Jallal) a Syrian refugee beggar. “Seeing the Syrian refugees arriving on foot in the utmost destitution, carrying their metal objects to sell like trophies or atlases, with extinguished eyes and raspy voices, walking on the sidewalks like dehumanized machines, gave me the idea for the film. I also saw and listened to the testimonies of Ethiopian domestic workers and saw a parallel between them. I found that the best way to narrate these two parallel lives is through a love story, because these people are not allowed love in the eyes of society. They are barely allowed to be human, let alone in love.”

Thus, from the point of view of its two protagonists, Mehdia the Ethiopian and Ahmed the Syrian, beautiful like two angels fallen from the sky in the wrong place, the film shows us the sad and cruel social injustice of the world in which they live: our own. But from their point of view. The film delves into the everyday life of an ordinary Beirut household where Mehdia works. Back in her country, Mehdia is promised by her parents to an old man she does not love, but she has fallen in love with the young Syrian refugee Ahmed who tries to survive by begging for metals at the windows of Achrafieh buildings so he can resell them by the kilo: batteries, copper, iron. Here, metal is the allegory of war, the metal of weapons and bomb shrapnel, of deep wounds, like the one Ahmed carries in his body, having been hit by a strange explosion that slowly transforms his body into metal.

Wissam Charaf follows the forbidden and difficult love of this damned couple with a gentleness that gives the film a tone of bittersweet romance. “The love story, which is the strongest link, acts by contrast. The environment is so harsh and thankless that their story is magnified, humanized. Both suffer. She is proud, confrontational; he is Christlike and suffers from an ailment that eats away at him from the inside. Doomed to wander, they seek a place, but their only refuge is their love, which is why I thought of the Stones song Gimme Shelter.”

By adopting their perspective, the film denounces, with internal empathy, a range of social problems present in our everyday life. It addresses the plight of domestic workers and their cultural and emotional isolation. It highlights issues especially present among disadvantaged Syrian refugees and their struggle to survive, as well as misogyny, machismo, xenophobia, cultural barriers, lack of openness to others, exploitation, the cruel absence of social rights, language barriers, makeshift shelters, refugee camps, the narrow-mindedness of ordinary people and the impossibility of a better future.

By adopting their perspective, the film denounces, with internal empathy, a range of social problems present in our everyday life. It addresses the plight of domestic workers and their cultural and emotional isolation. It highlights issues especially present among disadvantaged Syrian refugees and their struggle to survive, as well as misogyny, machismo, xenophobia, cultural barriers, lack of openness to others, exploitation, the cruel absence of social rights, language barriers, makeshift shelters, refugee camps, the narrow-mindedness of ordinary people and the impossibility of a better future.

“In my film, no one loves anyone, everyone finds someone inferior to themselves. I juggle the dynamics of power and domination with a lot of irony in this kind of Tower of Babel, where languages mix and no one understands the other.”

Closer in form to a Kaurismäki than a Ken Loach, it uses a film language with a poetic touch that is both sharp and touching, giving it its substance. The love scenes, luminous, are illuminated by the musical sounds of a particularly successful soundtrack by Zeid Hamdan, music that is suggestive without ever weighing down the atmosphere, resonating with sounds from Africa, nourished by African horns and organs.

There are some tricks and strong moments, some mesmerizing images that are unforgettable, like the breakfast scene on the hotel terrace where Mehdia and Ahmed, having won a free night in an extravagant hotel competition, appear like two beings bathed in sunlight in white billionaire robes on vacation. Wissam Charaf masters these winks that mix fantasy and the fantastical with the everyday. Like the reference to the vampire film Nosferatu: the old man for whom Mehdia works, a sort of avatar of Bela Lugosi (played by Rifaat Tarabay), watches this film on loop and reenacts it at night as a somnambulistic amnesiac, symbolizing the amnesia of a country that has also become senile, prey to its demons. Or Ahmed’s arm transforming into metal, like an iron arm, but then proving to be powerless and falling in the final scene in front of an impossible and limping horizon …

Produced by Aurora Films and co-produced by IntraMovies and Né à Beyrouth, based on a screenplay by Wissam Charaf, Mariette Désert and Hala Dabaji. Festivals: Venice 2022, Hamburg 2022, Montpellier 2022, 3 Continents, Audience Award at Belfort 2022, Franco-Arab 2022, Red Sea 2022, Thessaloniki 2023, Hong Kong 2023.

For more information, click here

Article by Maya Trad

https://www.agendaculturel.com/article/les-amours-refugies-de-wissam-charaf

Wissam Charaf chose this translation for the English title because, he says, “In professional jargon, the terms dirty, difficult and dangerous are qualifiers that enter into the classification of professions that are measured in degrees of danger. And here, we are far from the comfort zone.” Indeed, the two protagonists of the film have thankless jobs. Mehdia (Clara Couturet) is an Ethiopian domestic worker, and Ahmed (Ziad Jallal) a Syrian refugee beggar. “Seeing the Syrian refugees arriving on foot in the utmost destitution, carrying their metal objects to sell like trophies or atlases, with extinguished eyes and raspy voices, walking on the sidewalks like dehumanized machines, gave me the idea for the film. I also saw and listened to the testimonies of Ethiopian domestic workers and saw a parallel between them. I found that the best way to narrate these two parallel lives is through a love story, because these people are not allowed love in the eyes of society. They are barely allowed to be human, let alone in love.”

Thus, from the point of view of its two protagonists, Mehdia the Ethiopian and Ahmed the Syrian, beautiful like two angels fallen from the sky in the wrong place, the film shows us the sad and cruel social injustice of the world in which they live: our own. But from their point of view. The film delves into the everyday life of an ordinary Beirut household where Mehdia works. Back in her country, Mehdia is promised by her parents to an old man she does not love, but she has fallen in love with the young Syrian refugee Ahmed who tries to survive by begging for metals at the windows of Achrafieh buildings so he can resell them by the kilo: batteries, copper, iron. Here, metal is the allegory of war, the metal of weapons and bomb shrapnel, of deep wounds, like the one Ahmed carries in his body, having been hit by a strange explosion that slowly transforms his body into metal.

Wissam Charaf follows the forbidden and difficult love of this damned couple with a gentleness that gives the film a tone of bittersweet romance. “The love story, which is the strongest link, acts by contrast. The environment is so harsh and thankless that their story is magnified, humanized. Both suffer. She is proud, confrontational; he is Christlike and suffers from an ailment that eats away at him from the inside. Doomed to wander, they seek a place, but their only refuge is their love, which is why I thought of the Stones song Gimme Shelter.”

By adopting their perspective, the film denounces, with internal empathy, a range of social problems present in our everyday life. It addresses the plight of domestic workers and their cultural and emotional isolation. It highlights issues especially present among disadvantaged Syrian refugees and their struggle to survive, as well as misogyny, machismo, xenophobia, cultural barriers, lack of openness to others, exploitation, the cruel absence of social rights, language barriers, makeshift shelters, refugee camps, the narrow-mindedness of ordinary people and the impossibility of a better future.

By adopting their perspective, the film denounces, with internal empathy, a range of social problems present in our everyday life. It addresses the plight of domestic workers and their cultural and emotional isolation. It highlights issues especially present among disadvantaged Syrian refugees and their struggle to survive, as well as misogyny, machismo, xenophobia, cultural barriers, lack of openness to others, exploitation, the cruel absence of social rights, language barriers, makeshift shelters, refugee camps, the narrow-mindedness of ordinary people and the impossibility of a better future. “In my film, no one loves anyone, everyone finds someone inferior to themselves. I juggle the dynamics of power and domination with a lot of irony in this kind of Tower of Babel, where languages mix and no one understands the other.”

Closer in form to a Kaurismäki than a Ken Loach, it uses a film language with a poetic touch that is both sharp and touching, giving it its substance. The love scenes, luminous, are illuminated by the musical sounds of a particularly successful soundtrack by Zeid Hamdan, music that is suggestive without ever weighing down the atmosphere, resonating with sounds from Africa, nourished by African horns and organs.

There are some tricks and strong moments, some mesmerizing images that are unforgettable, like the breakfast scene on the hotel terrace where Mehdia and Ahmed, having won a free night in an extravagant hotel competition, appear like two beings bathed in sunlight in white billionaire robes on vacation. Wissam Charaf masters these winks that mix fantasy and the fantastical with the everyday. Like the reference to the vampire film Nosferatu: the old man for whom Mehdia works, a sort of avatar of Bela Lugosi (played by Rifaat Tarabay), watches this film on loop and reenacts it at night as a somnambulistic amnesiac, symbolizing the amnesia of a country that has also become senile, prey to its demons. Or Ahmed’s arm transforming into metal, like an iron arm, but then proving to be powerless and falling in the final scene in front of an impossible and limping horizon …

Produced by Aurora Films and co-produced by IntraMovies and Né à Beyrouth, based on a screenplay by Wissam Charaf, Mariette Désert and Hala Dabaji. Festivals: Venice 2022, Hamburg 2022, Montpellier 2022, 3 Continents, Audience Award at Belfort 2022, Franco-Arab 2022, Red Sea 2022, Thessaloniki 2023, Hong Kong 2023.

For more information, click here

Article by Maya Trad

https://www.agendaculturel.com/article/les-amours-refugies-de-wissam-charaf

Read more

Comments